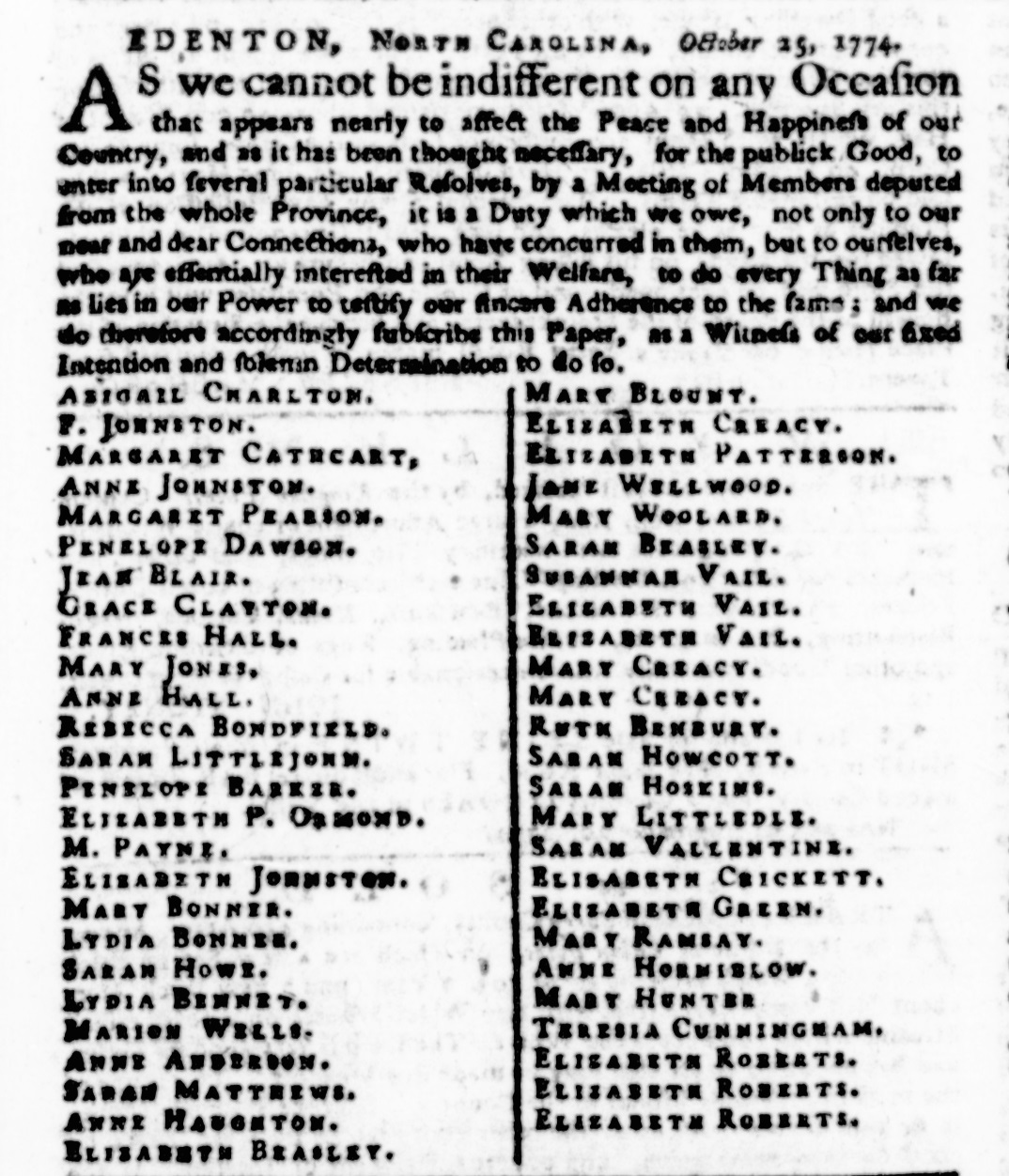

Legacy of the Edenton Tea Party Resolves

The Edenton Tea Party Resolves, 1774-2024

Edenton Teapot Sculpture

The story of the Edenton Tea Party Resolves has long served as a symbol of the town’s revolutionary spirit for its inhabitants. Local tradition states that Frank Wood, the early 20th century owner of nearby Hayes Plantation, commissioned the metal teapot sculpture based on a silver teapot owned by the revolutionary-era Johnston family.

Photograph of the Edenton Teapot Sculpture. A transcription of the inscription follows. Courtesy of the State Archives of North Carolina.

Made by a Frank Baldwin and installed in about 1905, the tea pot marks the location of Elizabeth King’s house, where Edentonians at the time believed the signing occurred. Mounted on a revolutionary-era cannon, the sculpture exemplifies Edenton's patriotic heritage and transforms a weapon of war into a platform for exhibiting the town's rich history.

Though today’s historians discount the Elizabeth King theory as legend, the tea pot sculpture still retains its important place in the town’s identity. Depictions of the teapot abound throughout Edenton, from the local newspaper to the town’s seal, solidifying the memory of the resolves as a core feature of the town’s identity.

Official seal of Edenton. Featuring the teapot sculpture, it reads "Town of Edenton, State of North Carolina, 1772." Courtesy of the Town of Edenton.

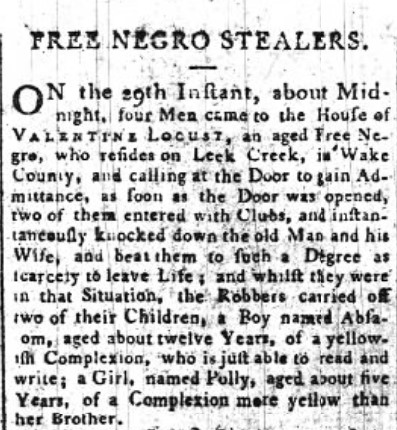

Edenton Tea Party Capitol Plaque

In 1908 the North Carolina Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution dedicated a bronze plaque in the State Capitol at Raleigh in observance of the Edenton Tea Party Resolves. Thirteen children, meant to represent the original colonies, unveiled the tablet.

The oval plaque features a large teapot in the center with a depiction of what historians of the time believed Elizabeth King’s house looked like. Below the house is a woman's hand dumping out a container of tea, a symbolic representation of the signers' boycott. Encircling the central design is a braided wreath of tea leaves, tea blossoms, and pine boughs.1

Meant to honor the signers, the plaque is dedicated to “fifty-one lades of Edenton, who, by their patriotism, zeal and early protests against British authority assisted our forefathers in the making of this republic."

Located in the central atrium of the capitol building, the women of the DAR hoped the tablet would inspire capitol building tourists and legislators alike.

Photograph of the Edenton Tea Party plaque, dedicated in 1908 by the North Carolina Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution. Courtesy of the North Carolina State Capitol.

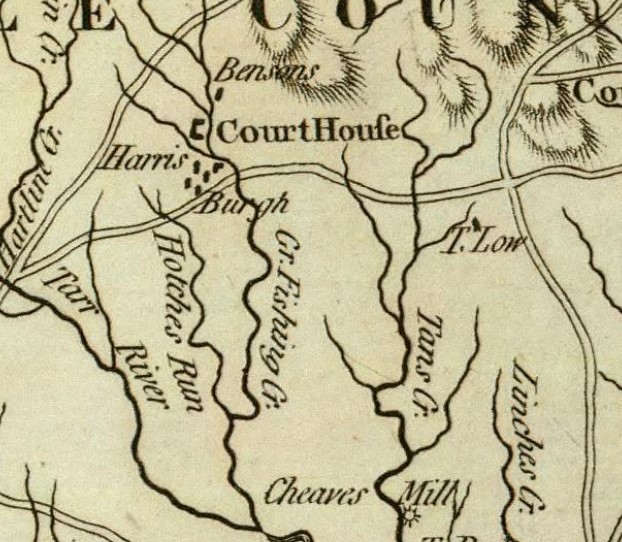

Edenton Tea Party Highway Marker

In 1940 the North Carolina Highway Historical Marker Program erected a marker for the Edenton Tea Party in downtown Edenton. Though the marker program now boasts over 1,600 markers throughout the state with at least one in every county, the Edenton marker was one of the earliest, established just five years after the program’s founding.

The original inscription for the marker identified the site of the signing at Elizabeth King’s house, but the current marker, last revised in 2015, omits King from the narrative and acknowledges the event’s importance as an “early and influential” act of “political activism” in the state.2

Photograph of the Edenton Tea Party marker. This version was erected in 2015, a transcription follows. Courtesy of the NC Highway Historical Marker Program.

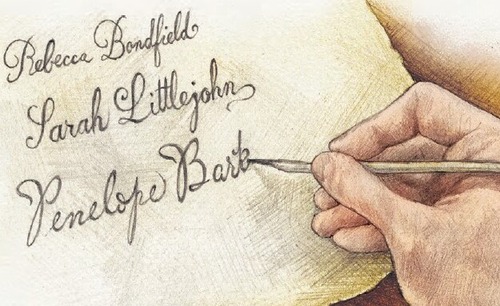

North Carolina History for Young Readers

The most recent commemorative effort of the Edenton Tea Party Resolves comes in the form of a children's book published by the State of North Carolina's Historical Research Office. As part of that office's ongoing commitment to educating and inspiring young North Carolinians we introduce:

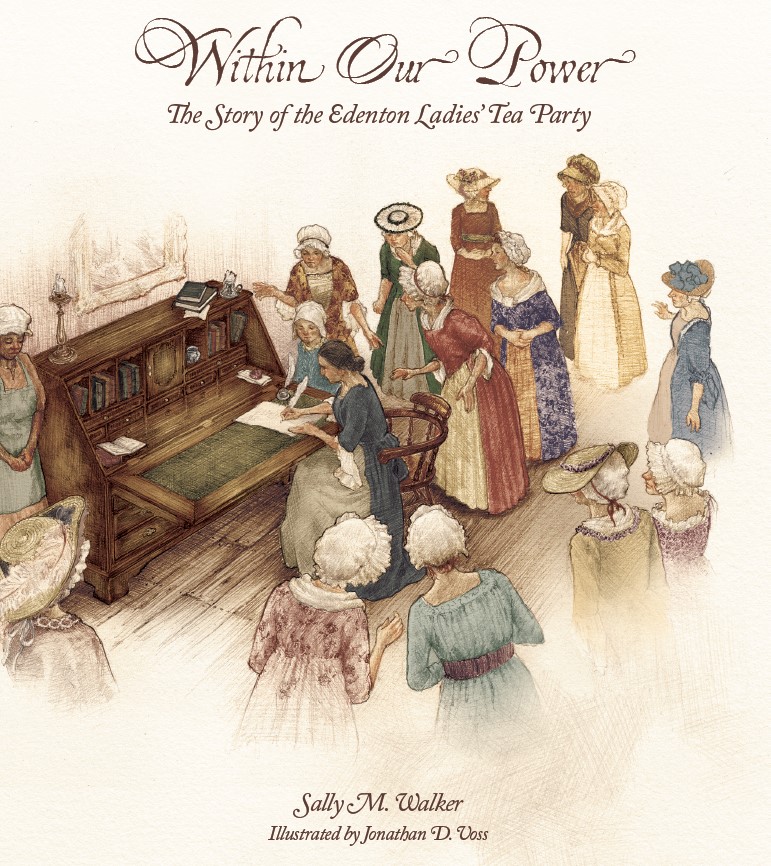

Within Our Power: The Story of the Edenton Ladies' Tea Party

by Sally M. Walker with illustrations by Jonathan D. Voss

Complete with twenty-eight pages of full-color illustrations, Within Our Power tells the story of the Edenton Tea Party Resolves and the women who signed them. Touching on themes such as fairness, courage, and civil responsibility, Within Our Power highlights how the fifty-one signers expressed their outrage at Great Britain's policies and, through signing their names, stood up in protest for their beliefs.

Front cover of Within Our Power, written by Sally Walker and illustrated by Jonathan D. Voss. Courtesy of the NC Office of Historical Research and Publications.

- "The Edenton Tea Party: Tablet Unveiled and Dedicated To-Day," Charlotte Evening Chronicle, 24 October 1908.

- "Edenton Tea Party, A-22," Marker Files, North Carolina Historical Highway Marker Program, Office of Historical Research and Publications, DNCR.

.png)

.jpg)