Seeking Shelter: Women as Refugees during the American Revolution

Seeking Shelter: Women as Refugees during the American Revolution

The tumultuous events of the American Revolution forced many people from their homes. Many thousands of American Indians and loyalists (both whites as well as people of color) lost their property as a result of the war.1 Yet when the tides of war turned towards British occupation, Patriots and their supporters also became refugees were also displaced from their homes and properties.

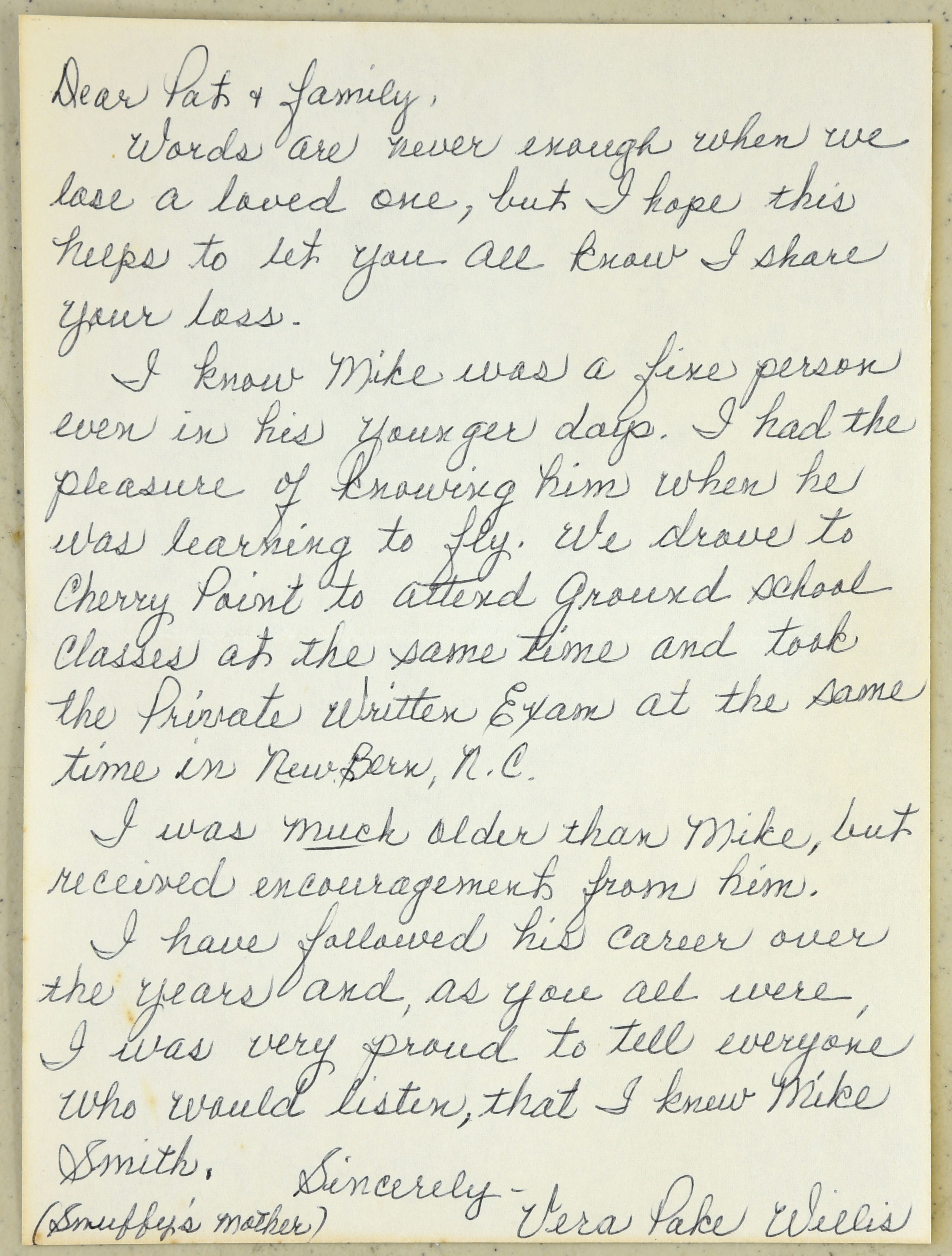

Two North Carolinian women who became refugees because of their Patriotic sympathies were Lucy Brown and Margaret Strozier. When the British approached, they, like many women, had no choice but to flee for their families' safety.

"Being small she was allowed to approach [where Col. Brown] was confined and to peep at him."

-Affidavit of Susan Wright in support of a Pension Claim for Lucy Brown, 3 April 1839

"She fled with her family of little children through South Carolina, half begging & starving"

-Application for a Widow's Pension from Margaret Strozier, 1 February 1842

Refugees not only faced the physical loss of their homes and the rigors of an oftentimes dangerous evacuation, but also the dealt with a profound sense of loss and uncertainty about their futures. For Lucy Brown, she and her parents had to evacuate from Wilmington to her husband's estate thirty miles away. When her husband was captured as a prisoner of war, Lucy sent her younger sister to the jail to visit him, as it was not safe for her to go herself. Margaret Strozier had to leave her home in Georgia when a group of loyalists destroyed it out of retaliation for her husband's involvement in the local Patriot militia. Margaret then walked with her children through two states to reach her husband's army camp in present-day Tennessee. Both Lucy Brown and Margaret Strozier, as well as countless other North Carolina women, showed remarkable fortitude when faced with the decision of fleeing their homes and protecting their families.

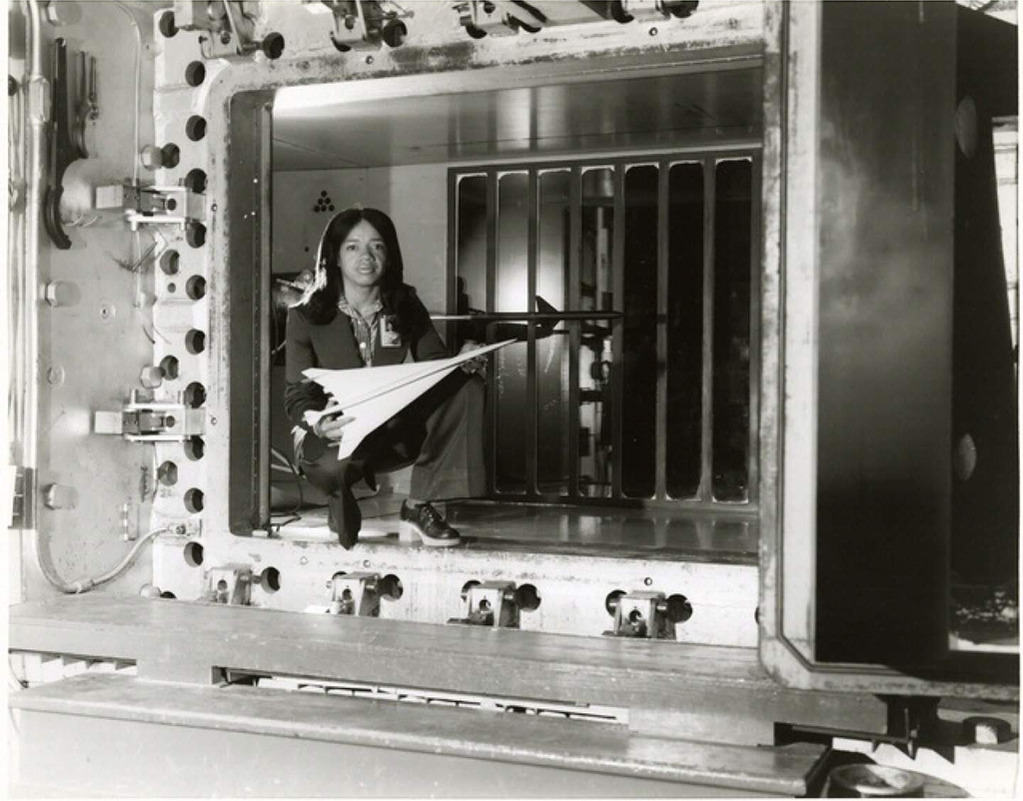

Engraving of a woman leading two children on a journey. Courtesy of New York Public Library.

North Carolina Widows in Their Own Words

The Colonel's Wife: Lucy Brown

Raised a Quaker in Chester, Pennsylvania and later Wilmington, North Carolina, Lucy Bradley took a dramatic turn away from her pacifist roots in 1780 when she married Thomas Brown, a colonel of the nearby Bladen County Militia. While her husband was away in service, Lucy might have stayed at her parents' home in Wilmington along with at least two other sisters. It wasn't long, however, until the dangers of being a military wife struck close to home. About a year after their marriage, the British army marched into Wilmington and occupied the city. The wife of a prominent Patriot officer, Lucy and her family had to flee the city and moved onto Thomas' estate in Bladen County.

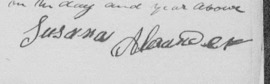

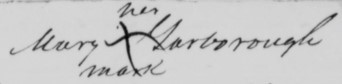

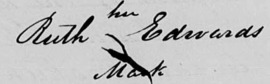

Lucy Brown's signature. Courtesy of National Archives.

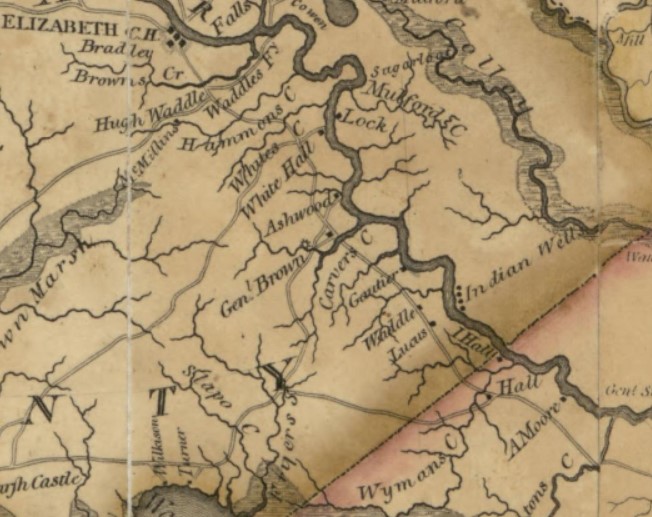

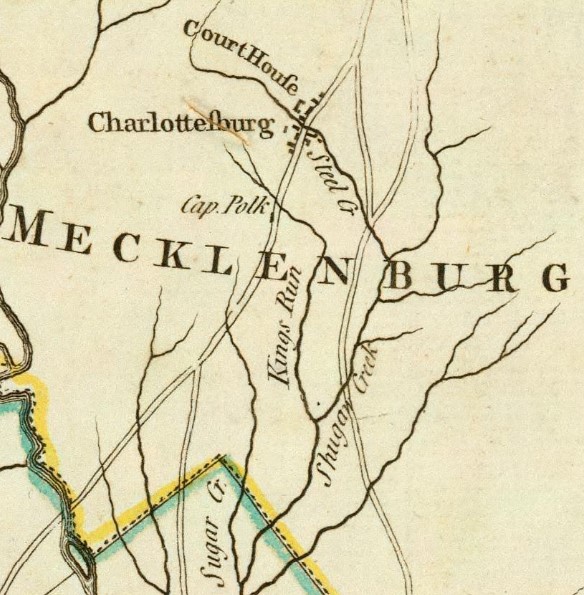

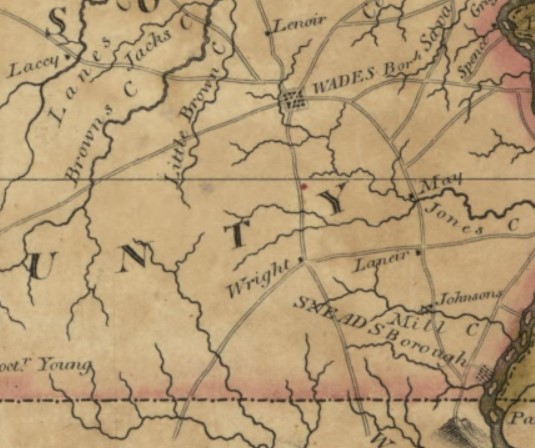

1808 Price & Strother map indicating the location of General Brown's home in Bladen County. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Later that month, Thomas Brown was severely wounded in the arm while leading an attempt to retake Wilmington. Though Lucy and her family tried their best to tend to his injuries, the colonel never regained use of his arm. That summer, Thomas Brown returned to his unit only to be captured by the British and imprisoned at the New Hanover County Courthouse in Wilmington, just a few blocks away from Lucy's father's home.

While her husband was a prisoner of war, Lucy Brown sent her younger sister Susan to check in on him. As a young girl aged eight or nine, Susan was innocent-looking enough that the British soldiers allowed her "to peep at" Colonel Brown through the prison bars and check on his welfare. When British forces left Wilmington in November 1781, Colonel Brown was freed and Lucy Brown's family finally returned to their homes in the city.

A Harsh Winter: Margaret Strozier

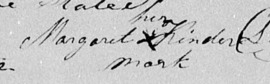

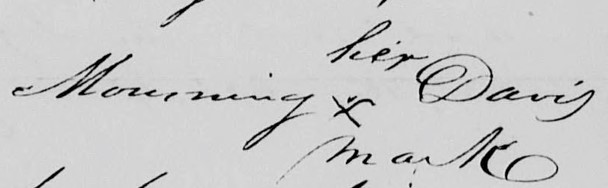

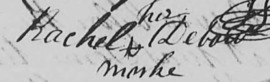

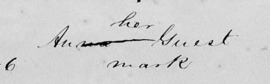

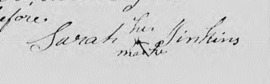

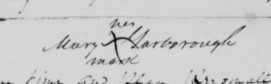

Margaret Strozier's signature mark. Courtesy of National Archives.

In December 1780 as she put her children in jackets, bundled up their meager belongings, and closed the door on the remains of her former home in Wilkes County, Georgia, Margaret Strozier might have contemplated what had brought her to this moment. Forty years old, she and her husband Peter had lived much of their lives in North Carolina. The couple moved to Georgia just prior to the American Revolution, likely in search of inexpensive land and better opportunities for their children. A couple of years later, Peter enlisted in a local militia regiment and from then on was away from home for most of the year.

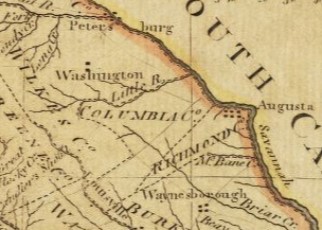

While Peter was away fighting, Margaret too was an ardent Patriot and joined other local women in feeding hungry American troops. Her husband's service and her own outspoken activity hurt her however. When the British took nearby Augusta, Georgia, she found herself firmly in loyalist-held territory with no protection. The Strozier farm, she later recalled, "was broken up" by loyalists "and every thing of any consequence destroyed."2

Faced with the prospect of supporting her family through the winter without adequate food or shelter, Margaret determined that her best option would be to find her husband, who was still attached to the Patriot army in the North Carolina backcountry.3 Leaving their home in Georgia, Margaret and her children, including newborn John, trudged through South Carolina "half begging & half starving" before finally finding her husband, having walked more than one hundred miles. The Stroziers became camp followers, travelling with and supporting the Patriot army by cooking meals and doing laundry. Following the war, the Stroziers rebuilt their home in Georgia.

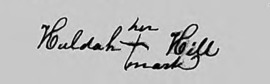

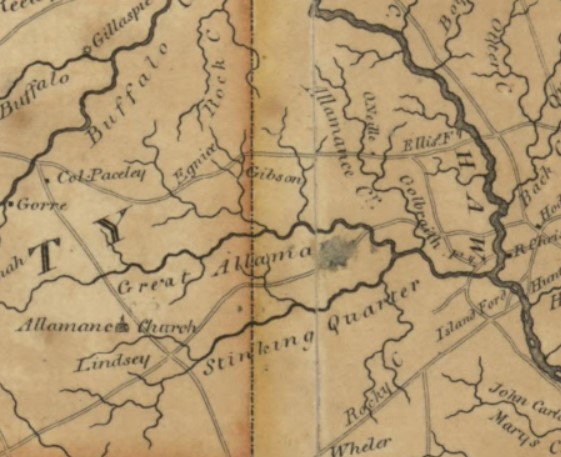

1796 Tanner map indicating the approximate location of the Strozier home in Wilkes County. Courtesy of Georgia Archives.

- Maya Jasonoff, Liberty's Exiles: American Loyalists in the Revolutionary World (New York: Random House, 2011); Cassandra Pybus, Epic Journeys of Freedom: Runaway Slaves of the American Revolution and Their Global Quest for Liberty (New York: Random House, 2007); Mary Beth Norton, Liberty's Daughters: The Revolutionary Experience of American Women, 1750-1800 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1980) 195-196.

- Charles C. Jones, Memorial History of Augusta, Georgia: From its Settlement in 1735 to the Close of the Eighteenth Century (Syracuse, NY: D. Mason & Co., 1890) 109. Patriot general Elijah Clarke failed to take Augusta in September 1780 and quickly retreated north through South Carolina to the North Carolina backcountry. As a form of retribution, British forces near Augusta began targeting anyone associated with Clarke's army, including noncombatants. As Peter Strozier was serving under General Clarke, the Strozier farm was one of about one hundred plantations and homesteads that the British destroyed. By staying in the area, even without their family farm, Margaret Strozier and her children might have faced additional dangers because her husband was a known Patriot.

- General Clarke's camp in the North Carolina backcountry was likely located in the region that later became Washington County, Tennessee. See Pension Application of John Waddill, 2 June 1854, (R10977), RG 15, National Archives; Wayne Lynch, "Elijah Clarke and the Georgia Refugees Fight British Domination," Journal of the American Revolution 15 September 2014 https://allthingsliberty.com/2014/09/elijah-clarke-and-the-georgia-refugees-fight-british-domination/ (accessed 29 December 2023)

.jpg)

_0.jpg)

.jpg)