On the Homefront: Women as Family Guardians during the American Revolution

With men away in military service, the American Revolution highlighted how women protected and managed their households. In some ways, women were the very lifeblood of the newly emerging American society. They grew the crops that fed the army, nursed wounded and sick soldiers back to health, and sewed and washed the soldiers' uniforms. Moreover, while at home, they raised and educated their children all while keeping a watchful eye out for British troops or loyalists who might try to attack them and rob them of their property. Women became family guardians, protecting and caring not only for their children, but also their war-weary husbands, brothers, and fathers.

"She had to watch while her husband and Murphy slept they had their swords... and a gun a pair"

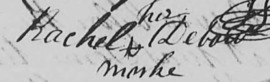

-Application for a Widow's Pension from Rachel Debow, 1 July 1837

"Her Mother went to see her father in the army and take some Clothing to him"

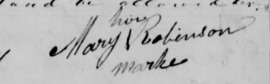

-Affidavit of Agnes Johnson in support of a Pension Claim for Mary Robison, 17 February 1835

"She prepard his Cloaths that her father made Nathan a pair of shoes"

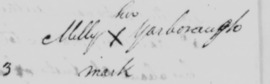

-Affidavit of Milly Yarborough in support of a Pension Claim for Nathan Yarborough, 5 August 1833

The term "family guardian" is all encompassing, and refers to the variety of ways women supported their families. While many of the duties that women assumed were not new, the American Revolution compounded women's responsibilities in unique ways. Mary English, for example, married Thomas Robinson and immediately became the stepmother to six children. A stepparent caring for their children is not novel, but because of the war, Thomas almost immediately returned to the militia after their marriage, leaving his children under Mary's sole supervision. Similarly Milly Yarborough had frequently sewn and washed her brother Nathan's clothing, but when he joined the militia, she and her father also had to coordinate delivering fresh clothing, shoes, and foodstuffs to him as the militia travelled by, making sure he had ample supplies to see him through the war safely. In these ways and many others, North Carolina women saw their families through the many struggles of the Revolutionary era.

Engraving of a woman watching a large group of children. Courtesy of New York Public Library.

North Carolina Widows in Their Own Words

The Night Watch: Rachel Debow

It was a clear, crisp day in late March 1781 as Rachel Debow dusted her hands and looked over her plowed field in Caswell County. Earlier that week, she had sown the whole field full of oat seed. Normally her husband Frederick would have done the farming, but he was away serving in the militia and there was no telling when he'd be back. Rumor was that some large battle had happened in nearby Guilford County.1 The British had won and now part of their army was camped nearby, possibly at a tavern called the Red House.

Rachel Debow's signature. Courtesy of National Archives.

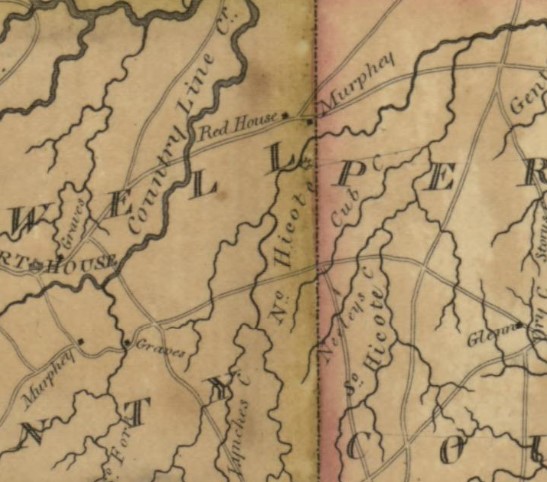

1808 Price and Strother map indicating the location of the Red House and Archibald Murphy's home. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

That evening, Rachel's husband Frederick and Major Archibald Murphy, her brother-in-law, appeared at the door. As she prepared meals and stoked the fire, Rachel asked them about the latest news from the Patriot army. The two men had stopped in to make sure she and the Debow children were okay, but the soldiers' presence also jeopardized Rachel and the children's safety, especially with several British patrols nearby. After the men finished their meals, they went to bed, each still clutching their officer's swords as they slept. Meanwhile, Rachel sat near their guns and kept watch through the night, ready to rouse her husband to defend their home should any British soldiers make their approach. Well-rested the next morning, the two men waved Rachel goodbye and set out to rejoin the American army.

While soldiers were out on tour, women like Rachel were also willing to defend their families. Whether their husbands were present or not, women had to be on constant alert for enemy soldiers who might try to seize their property. As their husbands and children were quietly asleep in their beds, women like Rachel took on the responsibility of seeing their families through the night.

Stepping in for Family: Mary Robison

Mary Robison's signature mark. Courtesy of National Archives.

When Mary English married Thomas Robison, she married into a family. The year prior, Thomas' first wife Rachel had died. Now as he marched off to join the Caswell County Militia, eighteen-year-old Mary found herself solely responsible for six stepchildren, including Agnes, who was five years Mary's junior, and Michael, an infant.

While Thomas was away in service, Mary travelled to meet him at his camp. Along with news from home, she probably brought him freshly laundered clothes and food. Meanwhile, Agnes watched her siblings, caring for her brother Michael in her stepmother's absence.

While their husbands were away serving in the Patriot army, women often served as their children's primary caregivers. In cases such as Mary's, women became guardians not only for their own biological children, but for stepchildren they had just met. While men were drafted to serve, women also made sacrifices to ensure the family's children were well cared for.

Uniform in the Making: Milly Yarborough

In June 1781 Milly was at home in Chatham County when she spotted a man coming up the walk. Although the man was disheveled and soaked from the recent rains, Milly might have recognized the uniform he wore, as she had washed it by hand many times. The man was her older brother Nathan, who she'd last seen six months prior when he marched off into service as part of the North Carolina Militia.

As her father ushered Nathan in to warm up by the fire and recount tales of his recent adventures, Milly busied herself with making her brother something to eat, getting him a fresh set of clothes, and drying out his knapsack. While Milly washed the mud out of her brother's uniform, she might have thought about how she had sewn his uniform for him when he was first drafted, or how she and her father brought him freshly laundered shirts and new shoes to the Patriot camp at nearby Ramsey's Mill earlier that year.

Milly Yarborough's signature mark. Courtesy of National Archives.

American soldiers needed women like Milly to make, repair, and clean their clothes. The Patriot army often depended on camp followers (women who travelled with the army) to sew and launder their clothing.2 In other cases, men like Nathan who had family nearby might depend on their female relatives to do such tasks. Proper laundering was essential for keeping the army organized and free from disease. Moreover, it was women like Milly who helped take care of former soldiers once they were formally discharged from service.

- The battle in question was the Battle of Guilford Courthouse, fought on March 15, 1781. Although the British technically won the battle, it was a pyrrhic victory and the aftermath of the battle helped General Nathanael Greene and the American army dislodge British control of South Carolina. See "Guilford Courthouse: A Pivotal Battle in the War for Independence," National Parks Service, April 2023, https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/upload/TwHP-Lessons_32guilford.pdf (accessed 18 December 2023).

- For more information about camp followers during the American Revolution, see Holly A. Mayer, Belonging to the Army: Camp Followers and Community during the American Revolution (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1996); Nancy K. Loane, Following the Drum: Women at the Valley Forge Encampment (Washington, DC: Potomac Books, 2009); Heather K. Garrett, "Camp Followers, Nurses, Soldiers, and Spires: Women and Modern Memory of the Revolutionary War," History in the Making, 9:5 (2016) 1-36.