Edenton Tea Party: Fact or Fiction?

Fiction: The Edenton ladies signed their resolves at a tea party.

In colorful retellings of the event, the refined ladies of Edenton gathered at a local home, sipped locally made tea, and signed resolves to stop buying British tea. In reality, the resolves never mentioned tea specifically. Moreover, they likely signed the resolves over the course of several days or weeks, meaning there was no singular large gathering of all the signers.

Rather than being an agreement to boycott the purchase of British tea, the Edenton Resolves actually signified the signers’ support of the resolutions the 1st North Carolina Provincial Congress had passed in New Bern in response to the Intolerable Acts. These resolutions included a boycott of all imports from the East India Company (including tea), a halt on exports to England, and the establishment of an independent, American-led Continental Congress.

Fact: British satirists called it a tea party to ridicule the resolves' signers.

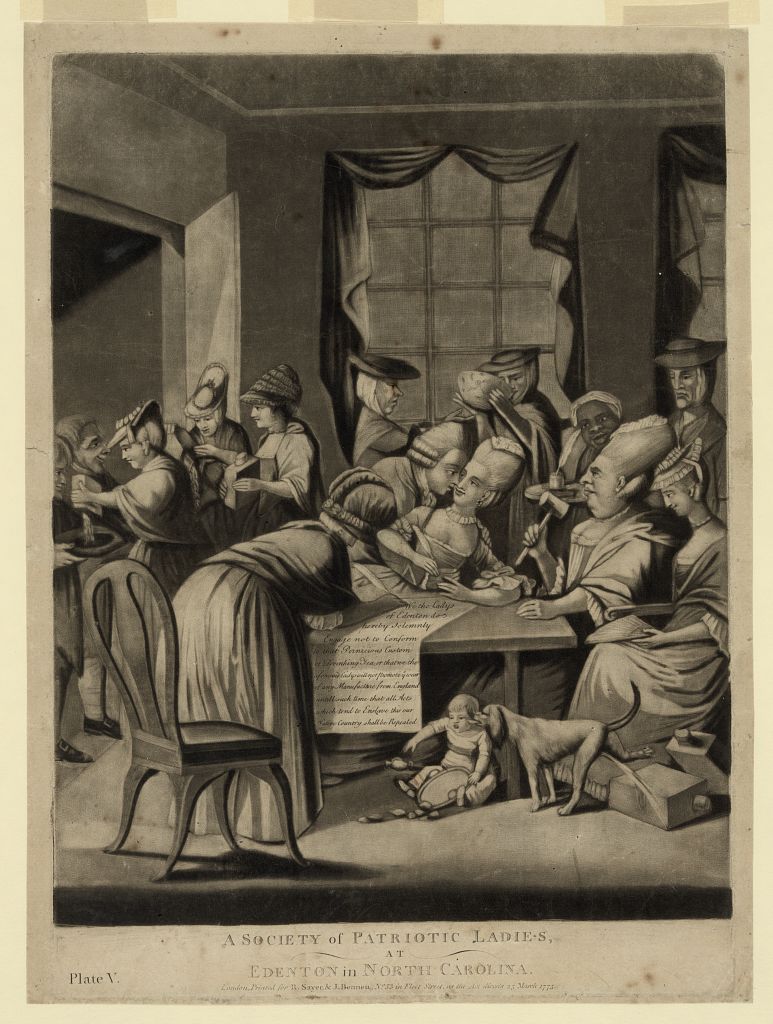

Perhaps the best-known image of the Edenton “Tea Party” comes from British cartoonist Philip Dawe. The image, below, depicts the Edenton ladies as vulgar impolite figures. They drink tea directly out of large communal bowls, dump tea into hats, and leave children unattended. In Dawe’s version of the resolves, the ladies solely promised “not to conform to the Pernicious Custom, of drinking Tea.”

By depicting the Edenton signers as impolite country folk and characterizing their resolution as a simple promise not to drink tea (all the while hypocritically still drinking tea) Dawes and other British opponents of the American cause tried to minimize or belittle the Edenton women and their political resolves.

This satirical cartoon, called "A Society of Patriotic Ladies, at Edenton in North Carolina" was drawn by Philip Dawe and printed in England in 1775. Meant to ridicule the Edenton women who signed the original resolves, the cartoon depicts the women as rude, impolite, and unclean. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Fiction: The signing happened during a gathering at Elizabeth King's house.

By the 20th century, tradition in Edenton held that the ladies signed the document together on October 25, 1774. As they affixed their names to the document, the fifty-one women observed the solemn occasion at Elizabeth King’s house near the Chowan County Courthouse while Winifred Hoskins served as the secretary for the meeting. However, if Elizabeth King and Winifred Hoskins did so much to facilitate the gathering, why didn’t they sign the resolves themselves?

It's hard to say why some historians have characterized the signing of the resolves as a singular event at Elizbeth King’s house. The most likely explanation, though unsatisfying, is that when 20th century Edentonians were looking to reconstruct the event of the Resolves signing, they looked for a home owned by a woman near to the Chowan County Courthouse, and the King house fit the bill.

In reality, deed analysis reveals that Elizabeth King’s property was quite small. As a woman of middling means it seems unlikely she would have enough room to host all fifty-one women.1 No primary sources associated with the Edenton Tea Party Resolves that name Elizabeth King or Winifred Hoskins have ever been located. It seems likely then, that King and Hoskins’ involvement is a 20th century fabrication.

Local historians supposed that the women would have signed the resolves near the Chowan County Courthouse, built in 1767. Courtesy of Historic Edenton.

Fact: The order of the signatures reveals that separate familial groups signed the document at different times.

Though seemingly arbitrary, the order of the fifty-one women’s signatures provides important clues both about how the signing occurred and who the women were.

Some women that signed together were clearly related. The three women named Elizabeth Roberts, for example, represent a mother, an unmarried daughter, and a daughter-in-law. Other familial ties, though less obvious, are just as important. Mary Littledale, Sarah Valentine, and Elizabeth Crickett also signed together in order. Like the three Elizabeth Roberts they are also a family group, representing a mother who had remarried (Littledale), a married daughter (Valentine), and an unmarried daughter (Crickett).

75% of the women who signed the document were directly related to at least one other signer. When more distant relations such as cousins are factored in, the percentage is even higher. Identifying these relations is important, and more than a simple genealogical exercise.

By determining which signers knew each other, we can get a better sense of how the signing occurred. Rather than being an act of individuals, families of women signed together. The resolves’ leader, possibly Penelope Barker (see section below), likely approached different groups of women over the course of several days or weeks and asked them to sign. Though the signers may have visited Edenton, it’s just as likely they took the document out to rural Chowan County, where most of the signers were from, and the document traveled from house to house collecting signatures.

These two ceramic tea caddies were supposedly owned by Penelope Barker and Mary and Lydia Bonner during the time of the signing. Courtesy of the North Carolina Museum of History.

Fiction?: Penelope Barker singlehandedly orchestrated the event.

Was Penelope Barker the President of an Edenton Ladies’ Patriotic Association? Maybe.

Although no archival evidence has ever been located, oral tradition suggests that Penelope Barker was the association’s ringleader. One of the signers did send a copy of the resolves to London, where it was printed in the newspaper.

Penelope certainly could have been the one to send a copy to England, but the evidence is inconclusive.

Fact: The event was a unique and early example of women's political activism.

The truth is historians likely will never know who exactly sparked the idea of writing the resolves. No primary sources from the time of the writing of the resolves have ever been located, so it is impossible to know whether Penelope Barker was the group’s leader and organizer.

Instead, historians can only interpret what we do know. Rather than focus on one “great woman,” we can celebrate the resolves as a bold act of women’s collective political activism, one of the earliest events of its kind in North America.

Illustration from Within Our Power: The Edenton Ladies' Tea Party depicting the signers gathered in debate. Courtesy of Jonathan D. Voss.

- Jerry L. Cross, "Postscript to the Edenton Tea Party," in Tar Heel Junior Historian (Sept. 1971), in "Edenton Tea Party, A-22," Marker Files, North Carolina Historical Highway Marker Program, Office of Historical Research and Publications, DNCR.