Project Gemini

Project Gemini

A highlight of the Gemini program was the successful space walk of astronaut Edward H. White II on June 3, 1965. Courtesy NASA.

NASA’s second phase of space exploration was called Project Gemini. Gemini’s ten manned missions flew in 1965 and 1966, successfully demonstrating man’s ability to live and work in space for extended periods of time.

Primary aspects of the Gemini program included the implementation of spacecraft built for teams of two astronauts, the development of safer reentry and splashdown procedures, the introduction of maneuverability options to spacecraft, and the advent of “extravehicular activities,” or walking in space.

Upon Gemini’s completion, astronauts and support staff were well prepared for the grueling six- to twelve-day missions of the Apollo program.

Rogallo Wing

In the early stages of Gemini, NASA engineers developed an alternative to the parachute landing “splashdown” method that had been used with Mercury spacecraft. One of their options was a kite-like parawing, the creation of long-time Outer Banks residents Francis and Gertrude Rogallo.

The Rogallos’ parawing would have allowed astronauts to steer the Gemini capsule back to Earth’s surface and land it much like any other aircraft. Testing proved the concept, but engineers ultimately opted to retain the parachute landing system. While the Rogallos had missed an opportunity for space fame, their flexible-wing technology revolutionized the sport of hang gliding and remains in use to this day.

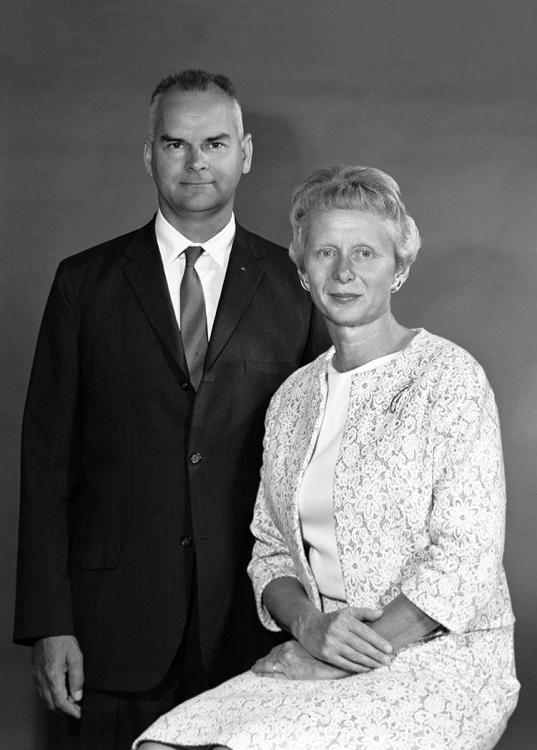

Long-time Outer Banks residents Francis and Gertrude Rogallo patented their wing design in 1951. Courtesy NASA.

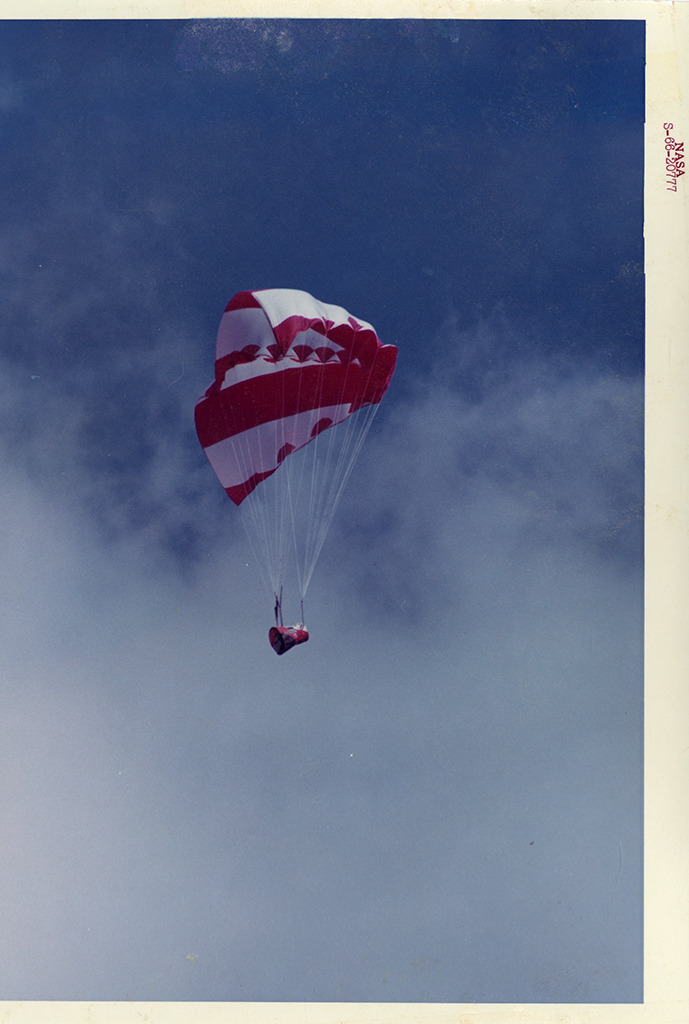

Development of the Rogallos' parawing, or paraglider, concept for application during the Gemini program received authorization in 1961. This photograph, taken during a drop test, shows the deployed paraglider with a Gemini boilerplate, or practice, capsule. Courtesy of the Outer Banks History Center, State Archives of North Carolina.

The primary goal of the parawing was to provide astronauts with a controllable landing system. As shown in this illustration by Paul Meltzer, the parawing would have allowed astronauts to make a controlled descent in order to land the capsule on land. Though testing proved the concept was reliable, several factors, including waning funding and intellectual support, prevented the wing's integration into the Gemini and Apollo programs. Courtesy National Geographic Image Collection.

As a NASA engineer, Francis Rogallo lobbied for the wing to replace the parachute landing system used during Project Mercury. NASA pursued the idea during the developmental years of the Gemini program. Here, a NASA technician assists in the testing of the Rogallos' design in 1965 at the Langley Research Center in Virginia. Courtesy of the Outer Banks History Center, State Archives of North Carolina.

Aerial view of the tracking station's campus around 1981, when the facility was transferred to the Department of Defense. Courtesy of Rowell Bosse North Carolina Room, Transylvania County Library.

Rosman Tracking Station

In 1963, NASA opened a Satellite Tracking and Data Acquisition facility on the edge of Pisgah National Forest near Rosman (Transylvania County). The chosen site exhibited several important qualities: it was government-owned, had an absence of light pollution, and was free of electromagnetic interference.

The base at Rosman, one of twenty-three located around the world, served as the primary east-coast tracking station for satellites and manned spacecraft. The base consisted of two dish-shaped antennas—one measuring an astonishing eighty-five feet wide—that sent and received commands, scientific data, and location information.

Photograph of the construction of the eighty-five-foot-wide dish, or ear, that "listened" for signals from manned and unmanned spacecraft at Rosman. Courtesy of Rowell Bosse North Carolina Room, Transylvania County Library.

View of construction underway on the tracking station in Rosman, around 1963. Courtesy of Rowell Bosse North Carolina Room, Transylvania County Library.

Agena Launch Director

A key goal of the Gemini program was to successfully dock a crew capsule with another spacecraft while in orbit, a skill that would have to be tested and perfected before the space program could take on the Apollo missions. Gemini astronauts practiced the maneuver using an unmanned spacecraft called the Agena Target Vehicle. The two vehicles required separate, but perfectly timed, launches from Cape Canaveral. Any minor delay on the ground impacted the ability of the two crafts to rendezvous in space.

The high-stress environment didn’t deter Lt. Col. LeDewey “Jack” Allen of the Air Force’s 6555th Aerospace Test Wing. From 1963 to 1967, the Alamance County native served as commander of the SLV-3 Division, an assignment that also made him the launch director for seven Agena Target Vehicle launches in 1965 and 1966. Working in tandem with colleague and Gemini launch director Lt. Col. John G. Albert, Allen was responsible for running final checks on the Agena and its Atlas booster before giving the “go, no-go” status to NASA’s deputy director of launch operations.

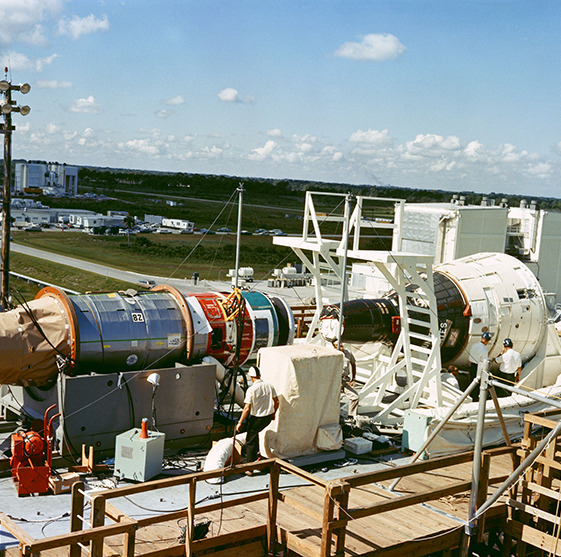

From Launch Complex 14, Lt. Col. Allen was responsible for overseeing the launch status of the Agena Target Vehicle, or ATV. The ATV was launched into orbit by an Atlas rocket, as shown here. This ATV was launched on March 16, 1966, for the Gemini 8 flight. Courtesy NASA.

NASA officials conducted a docking exercise of the cylindrical Agena Target Vehicle, left, and the Gemini 6 space capsule, right, at the Boresite Range Tower in August 1965. Courtesy NASA.

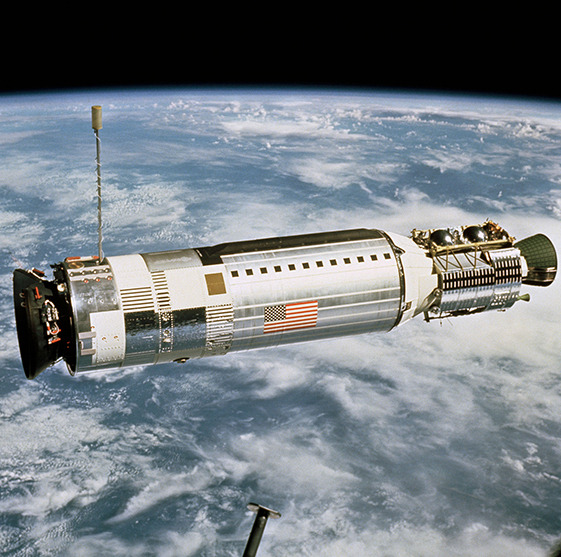

The ATV in orbit is shown here in November 1966. The photograph was taken from the Gemini 12 spacecraft from about fifty feet away. Courtesy NASA.

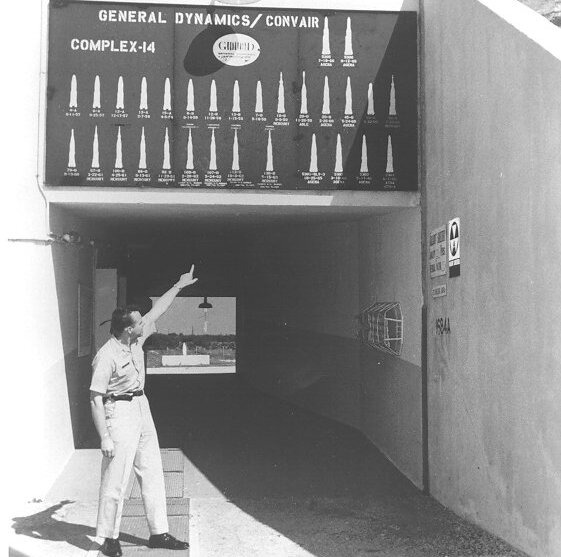

A view of some of the infrastructure of Launch Complex 14, from which the Agena Target Vehicle was launched. The unidentified man is pointing to a visual representation of all the successful launches from the complex. From Mark C. Cleary, The 6555th: Missile and Space Launches Through 1970, 45th Space Wing History Office.

.jpg)