"Sign of a Secret:" Recruiting to the Plot

"A Sign of a Secret:" Recruiting to the Plot

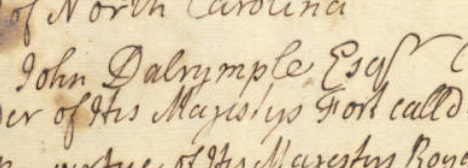

With their secret religious society now established, John Lewelling and his fellow members then had to find ways to recruit like-minded locals into their plot. In crafting the structure and recruiting process for the new society, Lewelling repeatedly referred back to religious terms and symbols.

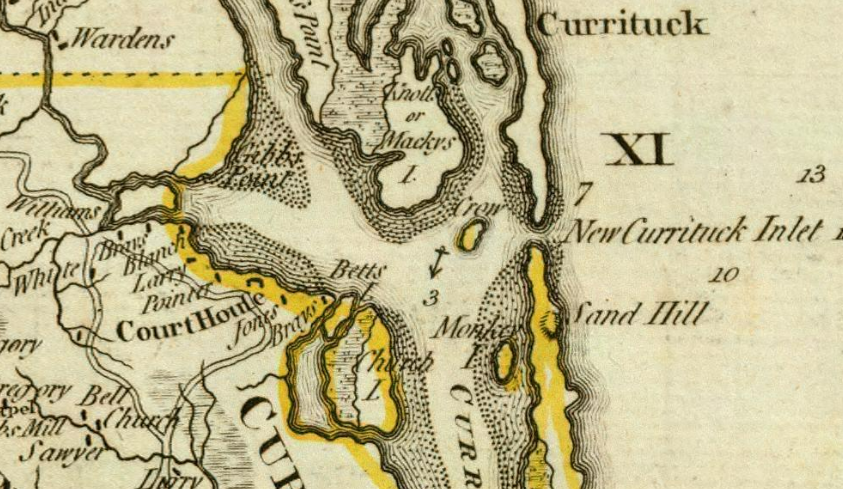

Lewelling enlisted the help of a small circle of supporters and appointed them as senior wardens for the society. The term "senior warden" alluded to the religious nature of the society and its goals. In the Anglican church, senior wardens occupied leadership roles in the congregation. They could hold religious readings and acted as an intermediary between the rector and the people. For Lewelling, his senior wardens would have the authority to swear new members into the society in his absence. They were also distributed throughout the area, so for example, while John Lewelling inducted new members in Martin County, Daniel Leggett did so in Bertie and Tyrrell Counties.

Finding likeminded locals eligible for induction into the society was another matter. Senior wardens in the society such as James Sherrard, Daniel Leggett, and John Lewelling designated certain trusted members of the society as recruiters, who could approach people, gauge their interest,and refer them to a senior warden for more information.

Recruiters often approached their own family members. John Garrett of Tyrrell County, for example, likely recruited five of his family members into the plot. Aside from approaching people at their own homes, recruiters also often took advantage of community events where groups of men gathered together.

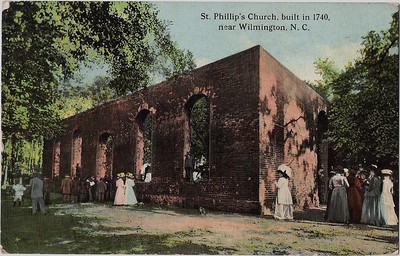

John Everett approached John Harrison and Thomas Rogers, both Tyrrell County farmers, at the end of a religious reading at Everett's father's house. Bertie County farmer Peleg Belote was recruited after attending a sermon near James Sherrard's house in Martin County.

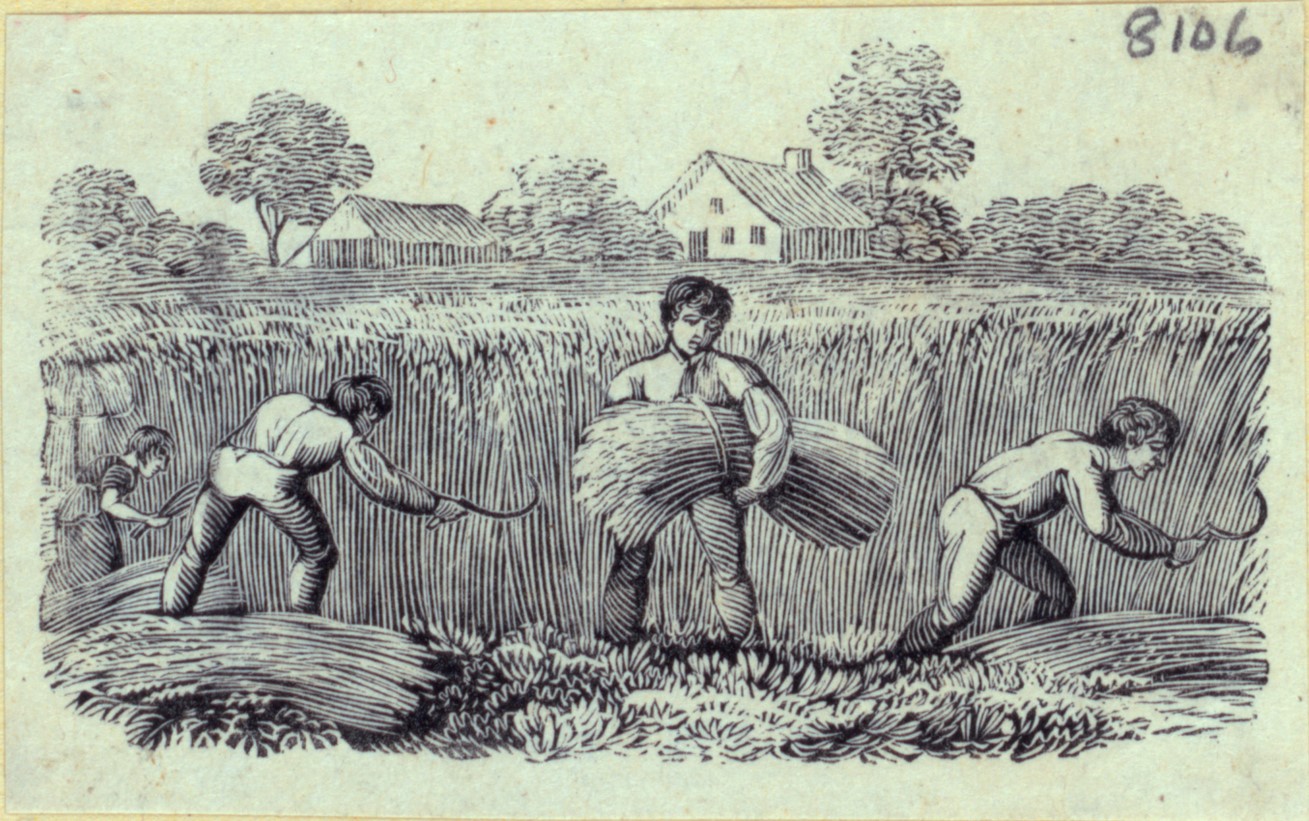

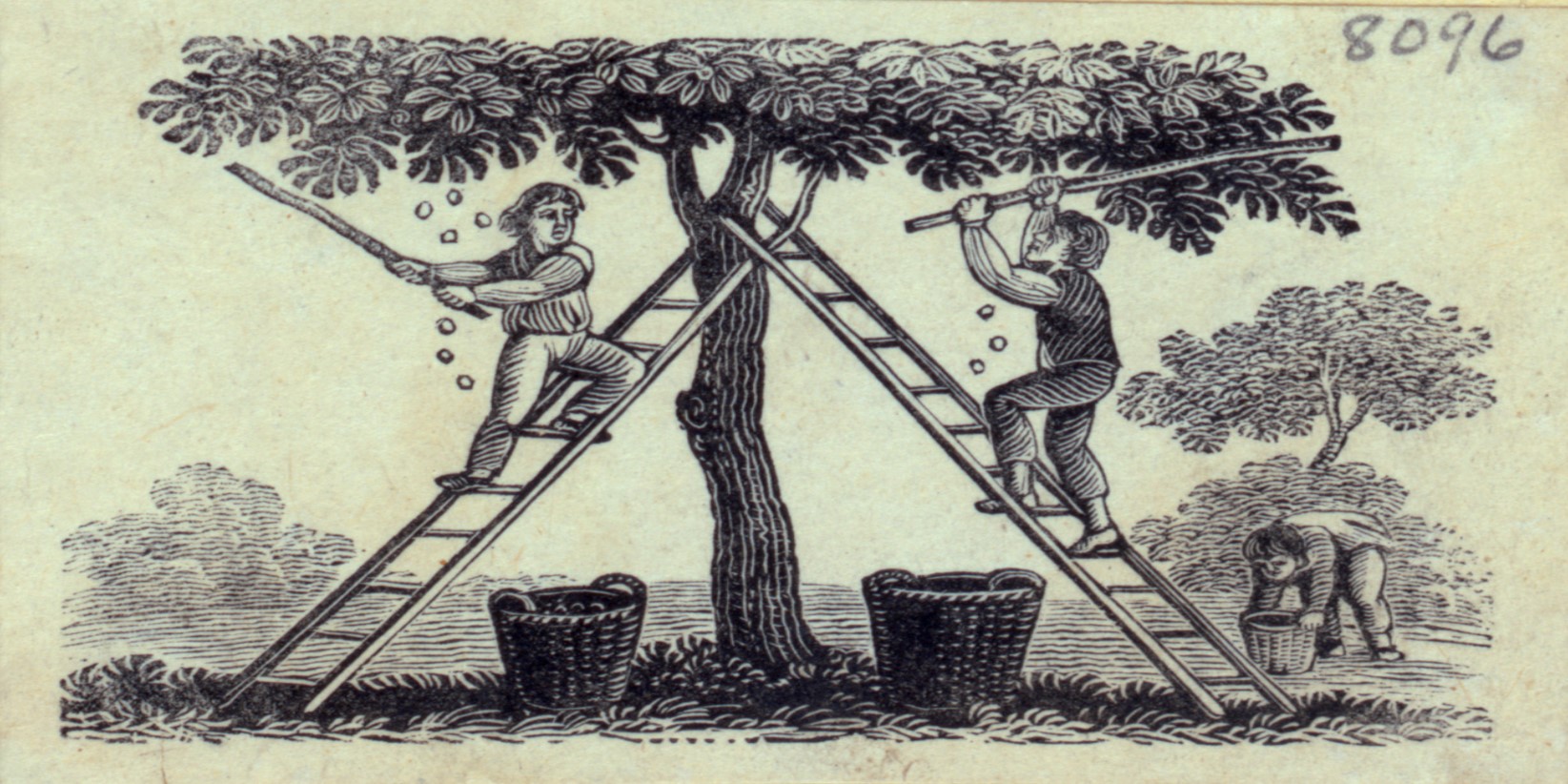

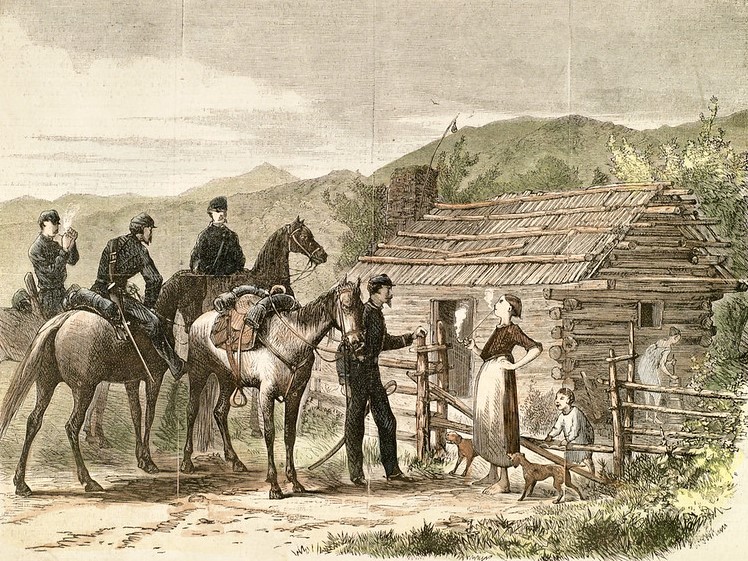

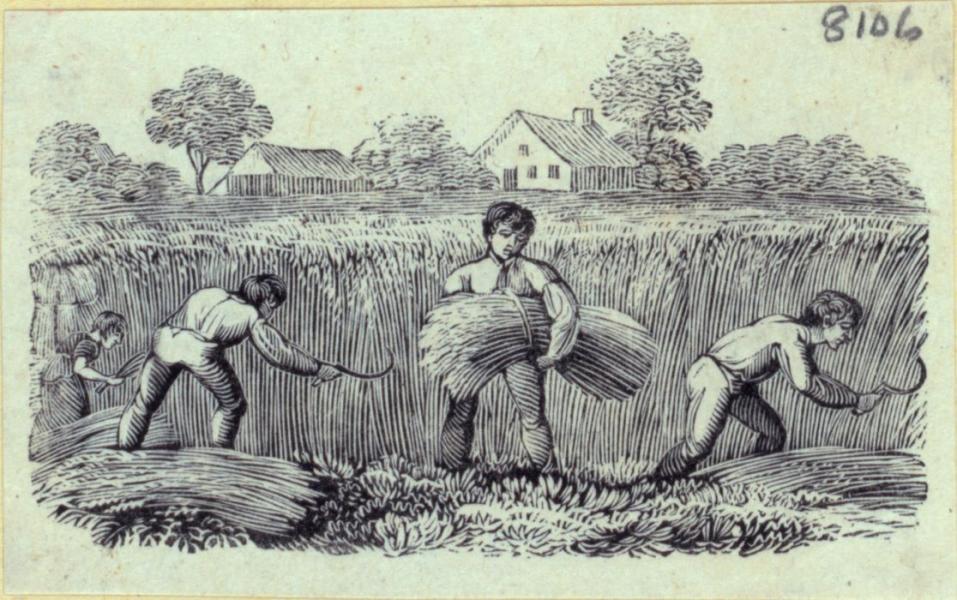

Daniel Leggett approached Stephen Harrison, Bird Land, and William Howard during a wheat reaping at Jonathan Davis' house, wherein men from the community visited one farmer's homestead to assist in the labor intensive tasks associated with harvest time. Several other members of the conspiracy mentioned gathering at Thomas Harrison's peach and apple orchards.

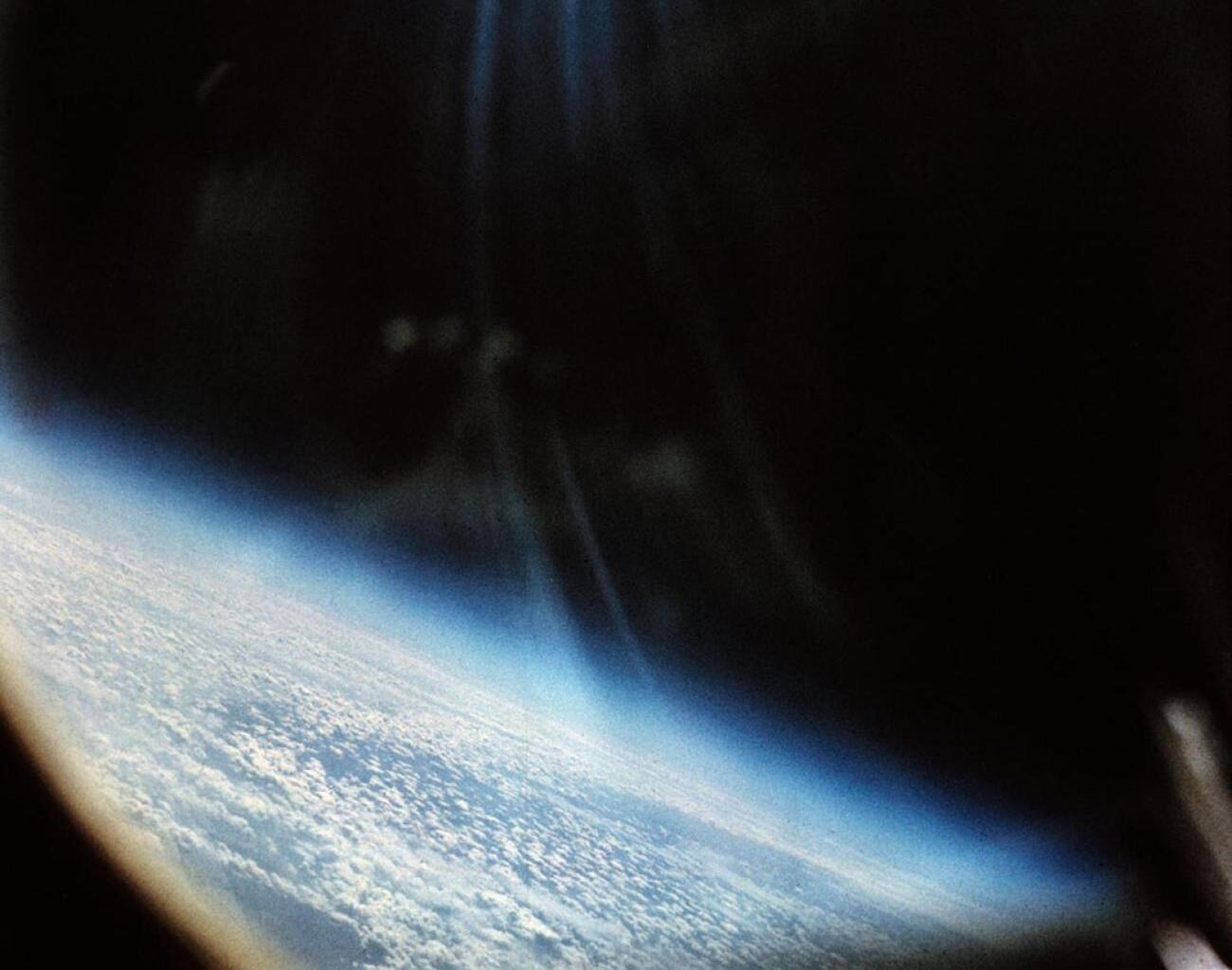

Engraving of farmers harvesting wheat by hand. Harvest season was a busy time, and community members often gathered together to help one another. Courtesy of New York Public Library.

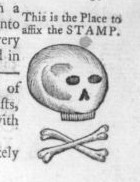

In nearly all cases, the recruiter would approach a potential member and engage him in a discussion about the threats to religion of the day. If he answered that he too wanted to protect the Protestant religion, the recruiter would take him to a secluded area where they wouldn't be seen or overheard, such as a quiet path, an isolated field, or inside a barn. There the recruiter would ask him if he could keep a secret. If the man agreed to swear to keep a secret, he'd make an oath and become a preliminary member of the society.

Still as a preliminary member, men had no idea what they had signed up for, except for that it was a religious organization meant to protect the Protestant religion. In order to get more information, the recruit would refer them to a senior warden in the area. Still, it was a secret society, so how could they approach a fellow member without raising suspicion? Like any good secret society, the Gourd Patch conspirators used a complicated system of secret signs and passwords.

New recruits received a special stick with three notches cut into it, with instructions to present the stick to a senior warden of the society. They were to present their stick to the warden, and the protocol was as follows:

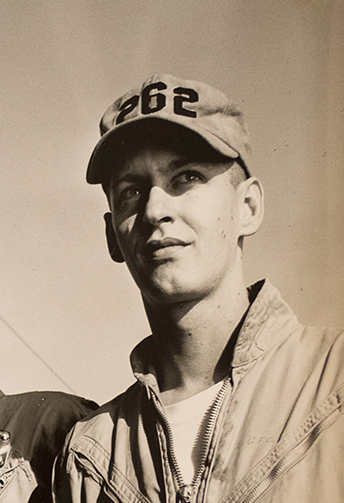

Engraving of farmers harvesting fruit trees. Several men joined the Gourd Patch Conspiracy at Thomas Harrison's orchard. Courtesy of New York Public Library.

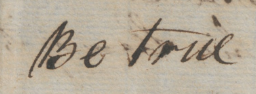

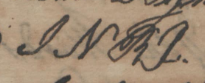

The religious symbolism in the secret signs of the society abounded. In some cases, rather than "Be True," the password was "INRI," an abbreviation of a Latin term meaning "Jesus the Nazarene, King of the Jews." As one historian has noted, the society's members were quite literally telling one another "to be true to INRI."

There were also numerous references to the holy trinity in the society's symbology. Aside from the three cut notches on the stick, one member, Charles Rhodes, was instructed to "shut Three Fingers of the left Hand and draw the fore Finger over the Face." Further when a provisionary member met with a senior warden, there were up to three additional secret oaths they could take. These signs and symbols all pointed back to how these zealous farmers of the Albemarle Sound wanted to observe and protect their religion and values.

Taking the Oath: The Extent of the Plot

It's difficult to be certain just how many people were involved in the Gourd Patch Conspiracy. Because of the system of regional senior wardens and recruiters, many members only knew the handful of fellow members with whom they'd been recruited. Even though John Lewelling is widely regarded as the leader of the plot, only nineteen members implicated him in the depositions that found their way to the archives. In contrast, Daniel Leggett, a senior warden for Bertie, implicated fifty four people in the plot (most of whom he swore into the society) but never named Lewelling, and may not have even been aware that he was the movement's founder.

Only some cells of the secret plot's network may have been uncovered by state authorities. When the plot was eventually discovered in July 1777, many members destroyed any evidence in an attempt to escape criminal charges. Further, the records for some counties may not have survived. Still, based on the extant historical records, it is possible to make some conclusions about the plot.

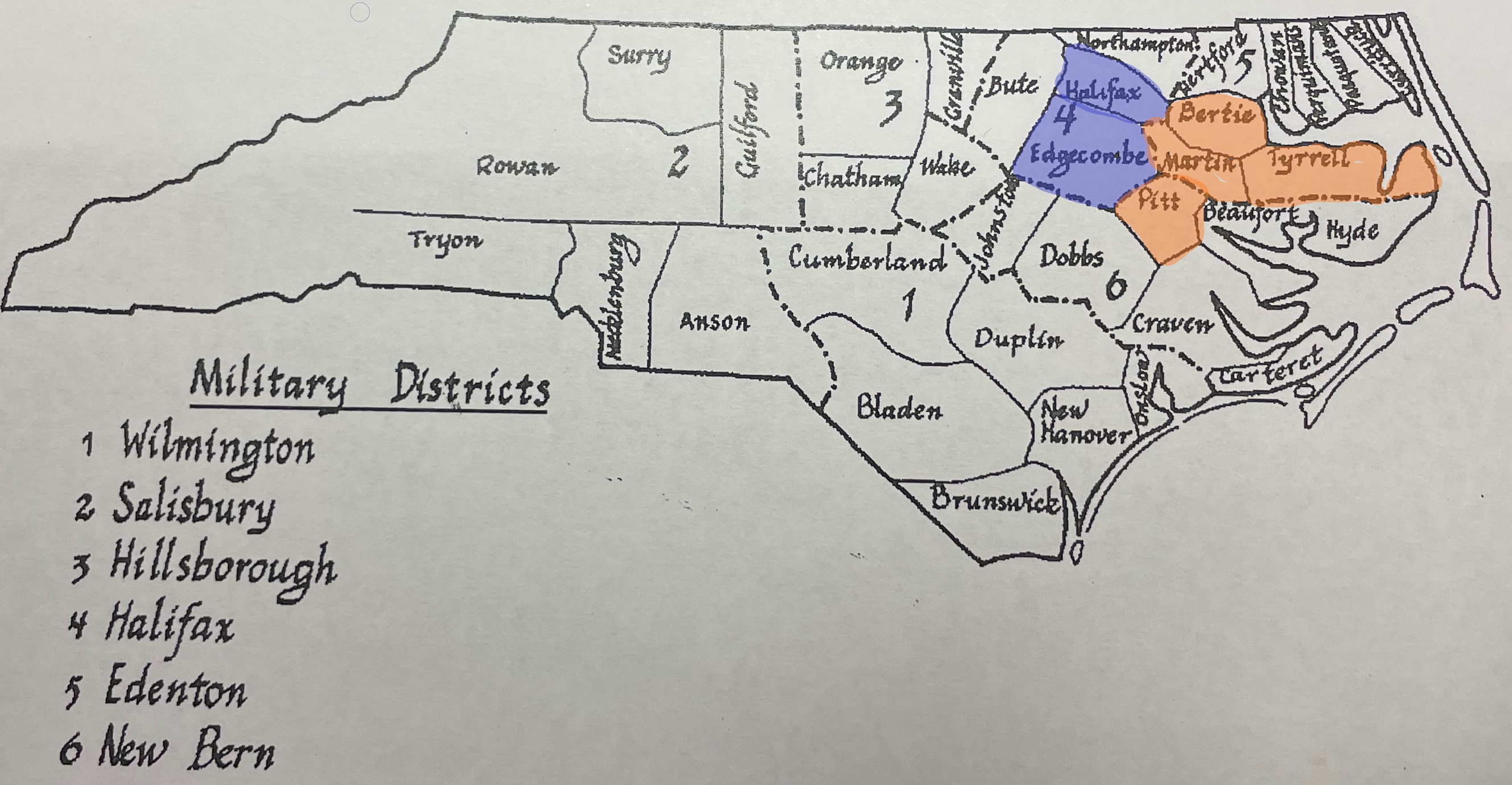

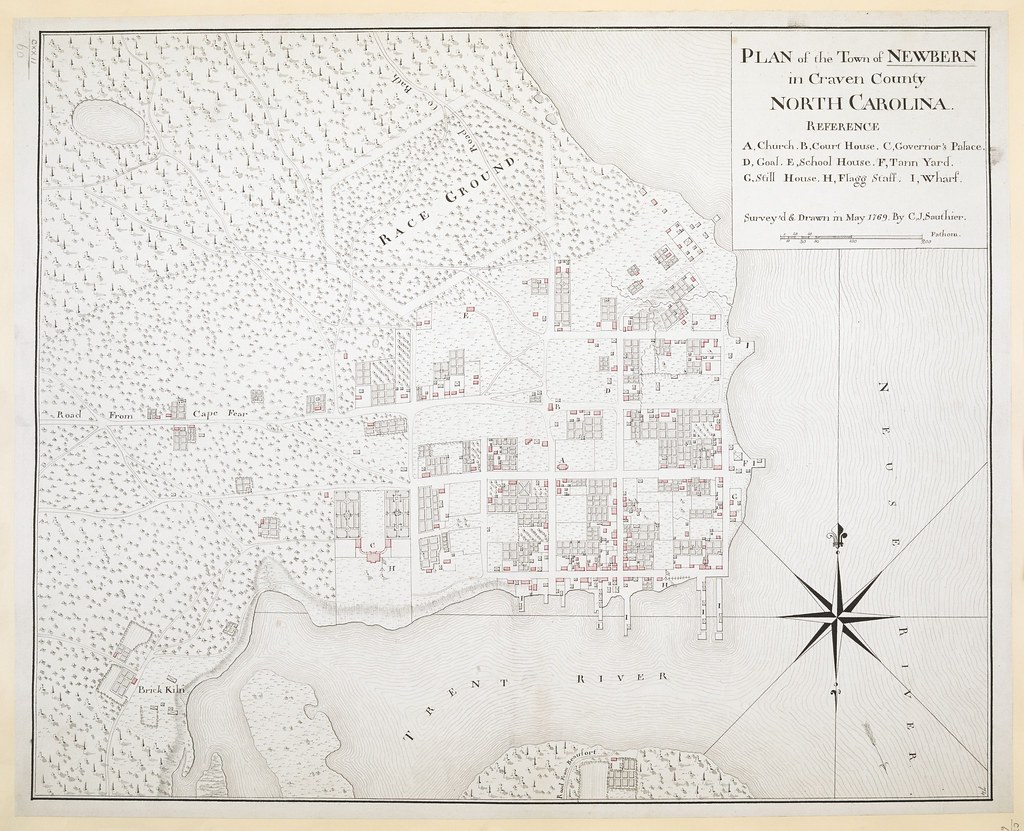

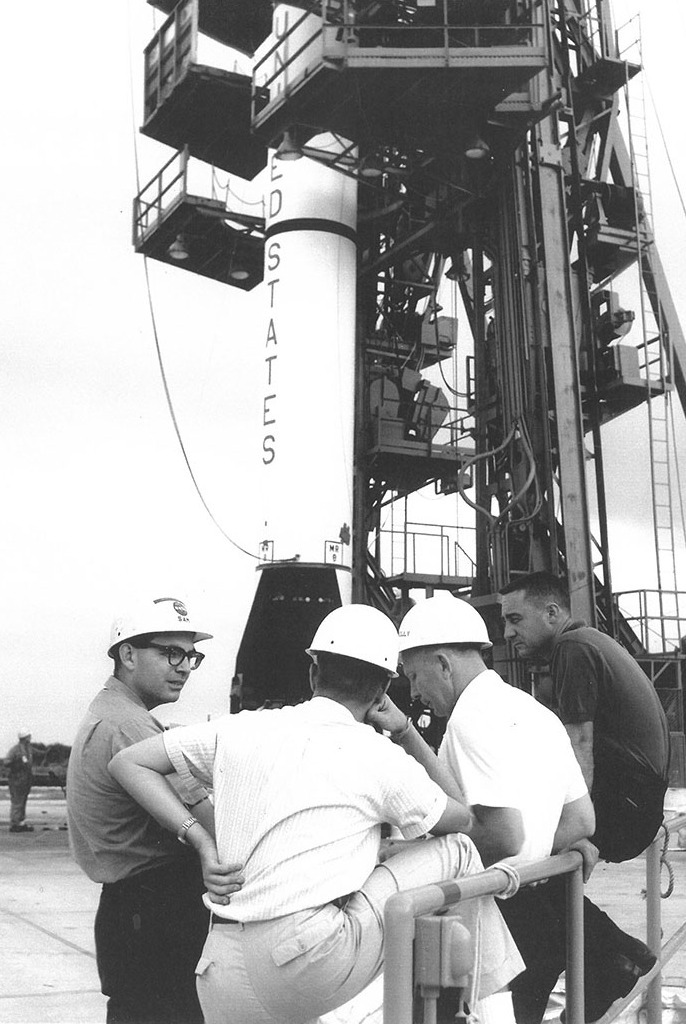

Only one membership list for the society survives--one from Daniel Leggett, a senior warden for Bertie. In it, he implicates fifty four individuals, most of whom are from Martin and Bertie Counties. A number of depositions survive which implicate men from Tyrrell and Pitt county as well. While some relevant sources suggest that the society also had supporters in nearby Edgecombe and Halifax Counties, no records exist which can prove that definitively. Below is a map outlining the possible extent of the movement:

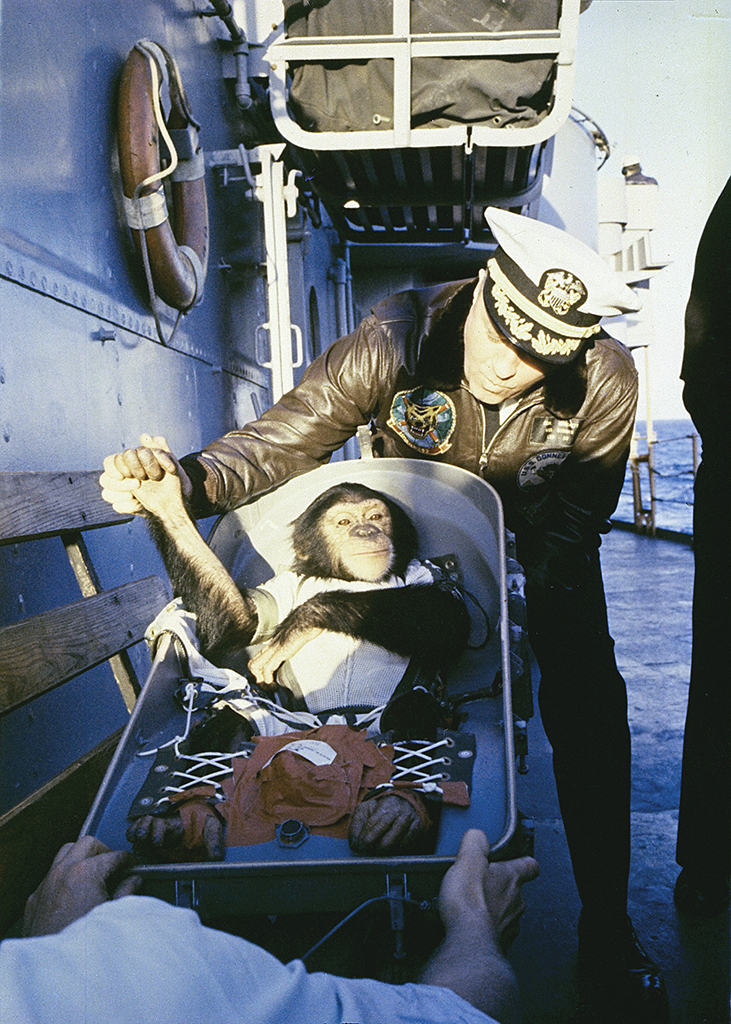

Map outlining North Carolina's counties and military districts at the time of the Gourd Patch Conspiracy. Counties highlighted in orange contain at least one confirmed member of the plot. Counties highlighted in purple were suggested to contain conspirators, but no records survive to prove such a claim. Courtesy Linda Reeves, State Archives of North Carolina.

Moreover, some members of the plot claimed that its extent went far beyond the Albemarle Sound. James Hays, a Martin County farmer, supposedly "travelled some thousand Miles endeavouring to get as many people to [Associate] as possible." William Skiles reported that he had learned the movement first started in Virginia, and that it also had supporters near the Haw River west of Hillsborough and also in South Carolina. Leggett claimed that the society extended as far south as Georgia. No evidence has been located which supports the claims that the plot operated to this large of an extent, however.