Treating the Wounded: Women as Nurses during the American Revolution

During the American Revolution in the rural Carolinas, armies had far less support infrastructure than in the northern colonies. Rather than calling on a fleet of regimental surgeons, many army commanders relied on area physicians. After a battle, an army surgeon or a local doctor might face a flurry of wounded men from both sides demanding their attention. Further, the nature of 18th century medicine was such that wounded men would still have a long road to recovery. Supporting short-staffed doctors and tending the sick and wounded, thousands of women served as nurses.1

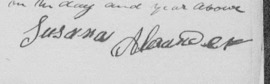

"Susan Alexander being Instrumental, in saving the life of Captian Joseph graham."

-Affidavit of John Allison in support of a Pension Claim for Susana Alexander, 21 September 1851

"She went over... with a waggin... and braught home Peter Kinder who was wounded"

"Her brother the Capt. was shot with a ball broke his Collar bone & lodged in his Shoulder"

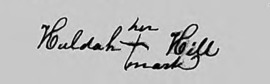

-Application for a Widow's Pension from Huldah Hill, 3 February 1838

"She went to Orangeburg where he was sick... to see... and take care of him."

-Application for a Widow's Pension from Rosana Murray, 30 October 1842

"After he entered the service her oldest child James Ray sickened and died."

-Application for a Widow's Pension from Lydia Ray, 10 February 1837

"His mother came in afterwards & stayed with him until he got well."

-Affidavit of Thomas Yarborough in support of a Pension Claim for Mary Yarborough, 27 April 1852

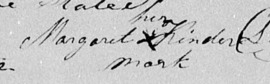

Not only did women provide medical care, but they also served as advocates for their loved ones while they were in field hospitals, filling in where doctors could not. If loved ones received word that a relative had been wounded or fallen ill while in the army, male relatives often went out to find them. In rarer cases, wives or sisters left their homesteads and ventured out to look for their loved ones themselves. Margaret Kinder, for example, left her home in Virginia and crossed the Blue Ridge Mountains to find her husband, who had been wounded at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse.

When men were able to return home on their own, their wives and sisters took on the primary responsibility of caring for them. After Mary Yarborough’s husband was shot in the spine during the Battle of Halifax, a British surgeon removed the bullet, but it was Mary’s duty to nurse her husband back to health. Similarly, Huldah Hill's brothers came home from the Battle of Beatti’s Bridge wounded. As she tended to their injuries, she learned her husband had sustained “several wounds on the head,” been captured by the British, and now needed her care as well. Women were not just caretakers of their own loved ones either. After the Battle of Charlotte, Susana Alexander sheltered her neighbor Capt. Joseph Graham, who had such a severe head wound that "some of his brains exuded."2

Engraving of a woman sitting by a sick man's bedside. Aside from parenting the children, women were also responsible for caring for sick or wounded family members. Courtesy of New York Public Library.

Through an informal system of cooperation, rural women helped the men in their communities recover from their war wounds and diseases. Below are examples of how some North Carolina women undertook new roles as nurses and nursing advocates during the Revolution.

North Carolina Widows in Their Own Words

Behind Enemy Lines: Susana Alexander

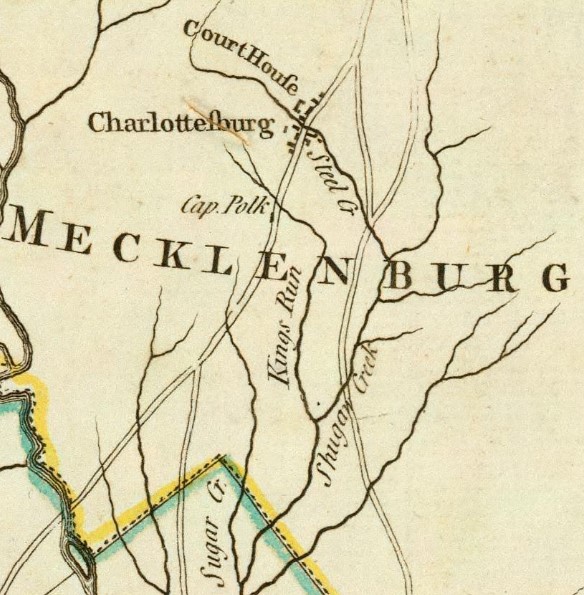

One morning in September 1780, Susana Alexander went to the Sugar Creek spring in Mecklenburg County. She needed water, but Susana approached the spring cautiously, unsure of who she might find. The day prior Patriot forces had fled when British troops invaded nearby Charlotte. Roving bands of enemy cavalry might be nearby. As Susana approached the spring, she found not a British officer, but an American one: Capt. Joseph Graham.

During the battle Captain Graham had led a group of cavalry in stalling the British dragoons while the remainder of the American army retreated to safety. In the course of that mission, British dragoons knocked Graham from his horse and wounded him severely, leaving him for dead. Mustering all his strength, Graham had dragged himself from the battlefield towards the spring, bloodied and semi-conscious.

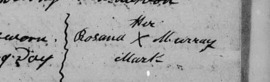

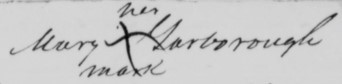

Susana Alexander's signature. Courtesy of National Archives.

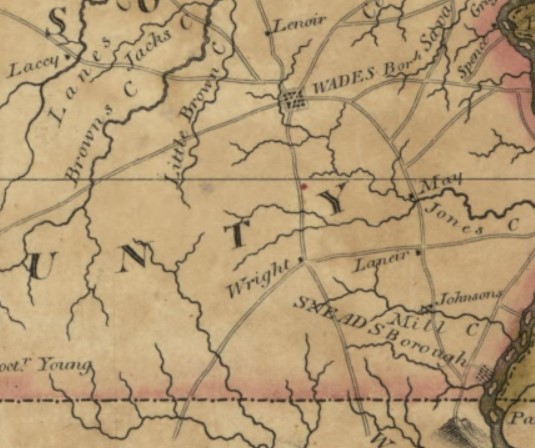

1776 Mouzon Map indicating the location of Sugar Creek.

Susana quickly sprang into action, putting Graham on her pony and bringing him back to her family's house, where she and her mother tended to him. They alerted Graham's men to their captain's condition and whereabouts, but the Alexanders worked in secret for fear the British might take Graham prisoner. Though they did their best to nurse him, the Alexanders worried Graham's multiple sabre and bullet wounds were mortal.

Due to Susana's efforts, Graham's men were able to evacuate him behind Patriot lines the next day. After several months recuperating, he rejoined the North Carolina Militia, attaining the rank of major. Even decades later, Major Graham credited Susana with saving his life—so much so, that Graham named his son William Alexander Graham, perhaps in Susana's honor. William Alexander Graham later fulfilled his family's debt and was instrumental in helping Susana receive recognition for saving his father's life and a pension.

Over the Blue Ridge: Margaret Kinder

Margaret Kinder's signature mark. Courtesy of National Archives.

Margaret Kinder was at her farm in Montgomery County, Virginia when she learned her husband Peter had been shot in the leg during the Battle of Guilford Courthouse and brought to Salem, North Carolina for treatment. Leaving her eighteen-month-old son George in the care of his aunt and a loyalist refugee who was living with her, Margaret and her brother-in-law Philip Kinder hitched a horse to a cart and started a one-hundred-mile journey over the Blue Ridge Mountains to bring Peter home.

Margaret was no stranger to long journeys. Seeking better opportunities outside of war-torn Palatinate Germany, Margaret's parents immigrated to Pennsylvania when she was nine. By age twenty, Margaret had found herself facing another war—the American Revolution—and she and Peter were trying to do their best to protect their son. Peter was a private in a local regiment of the Virginia Militia, but his unit left him in Salem when his wound made him unfit for travel.

In Salem, Peter's care was now left to a overburdened doctor who was unable to provide one-on-one treatment to his many patients. Not content to sit by and pray for his recovery, Margaret went to find Peter and ensure that he was receiving the best treatment. After making her way to Salem, a place Margaret had likely never been before, Margaret stayed with her husband and provided that vital nursing care herself.

Once he was stable enough, Margaret and Philip loaded Peter into a cart and began their return trip over the Blue Ridge Mountains to Virginia. Thanks to Margaret's care, Peter survived the war, living until 1809. Over sixty years after the event, people on Margaret's pension application recalled how remarkable Margaret's long journey to save her husband was.

A Military Family: Huldah Hill

Teenaged Huldah Jackson was living on her family's Anson County farm when a recent arrival from Halifax, John Hill, caught her eye. Huldah came from a prominent local family, with Huldah's father and oldest brother serving as local militia officers. When Huldah and John began courting, Huldah's father disapproved, likely because John was a new arrival and fifteen years Huldah's senior. Still Huldah and John wanted to be married. While her father was away in service, Huldah snuck away from her home to meet John, and they married in secret.

Huldah Hill's signature mark. Courtesy of National Archives.

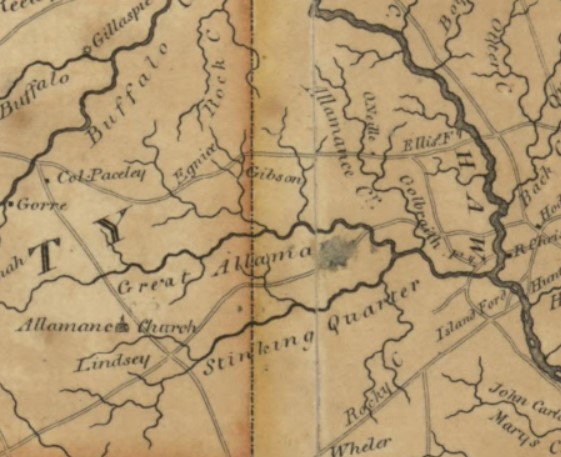

1808 Price and Strother map indicating the approximate location of the Jackson and Hill homesteads. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Although the Jacksons initially disapproved of the marriage, they welcomed John into the family, perhaps more than even John had intended. A few months after their marriage, John was drafted into the Anson County Militia, where he served with Huldah's two brothers under the command of John Jackson, his father-in-law.

John Hill and the Jackson men marched off into service leaving Huldah behind to manage her growing family. In August 1781 Huldah, with two babies under a year old, likely feared the worst when she learned that her two brothers had been seriously wounded and her husband captured at the Battle of Beatti's Bridge.

Her brother Jonathan was shot in the shoulder. The other, Isaac, was shot in the mouth, knocking out some of his teeth. When John Hill finally returned home on a parole from the British army, he too had a serious head injury. Huldah quickly devoted herself to tending to the men. Due to Huldah and the other Jackson women's nursing care, all three men made a recovery and survived the war.

Finding the Missing: Rosana Murray

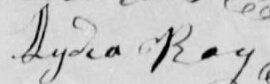

Rosana Murray's signature mark. Courtesy of National Archives.

Rosana Murray was about eighteen when she married John B. Murray in Rowan County, North Carolina. Her husband soon joined the Patriot army, leaving Rosana to raise the couple's growing family. In July 1781, John fell sick while stationed in South Carolina and was unable to return home. Hearing of her husband's fate, Rosana left her three children (all under the age of four) in a loved one's care and went to Orangeburg to find her husband.

According to Rosana's later recollection, upon his arrival at the field hospital in South Carolina, John had been so poorly that doctors were unsure of his name or identity. When Rosana arrived she had to walk through rows of cots, trying to recognize her husband in the mass of wounded and sick men.

Rosana found her husband and provided him with nursing care until he recovered. She likely brought foods from home to feed him, changed his clothes, and gave him the comfort of a familiar face. Other soldiers, who were alone and more dependent on the doctor's periodic check-ins, might not have fared so well. John, due in great part to Rosana's attentions, made a full recovery and rejoined his family.

Two Funerals and a Baby: Lydia Ray

In the fall of 1780 in Orange County, Lydia Ray had more household duties than there were hours in the day. With her husband Joseph away in the militia and four children under age nine and a fifth on the way, Lydia managed the busy harvest season. Her brother and sister-in-law had recently moved into the Ray home after being harassed by loyalists, and they might have helped her bring crops into the barn or tend to the Ray's cattle herd.

Lydia's troubles compounded when her oldest son, James, fell sick. James deteriorated quickly, growing weaker and weaker. Lydia stayed by her son's bedside, willing him to recover. Yet, fearing the worst, she sent word to her husband telling him to return home as quickly as possible to see their son.

Lydia Ray's signature. Courtesy of National Archives.

1808 Price and Strother map indicating the approximate location of the Ray homestead. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Leaving his regiment on a furlough, Joseph rushed home to see his sick son, getting there just before James died in late November or early December. In mourning, Joseph found himself unable to return to his regiment when he too fell sick, likely catching whatever illness James had. Lydia shifted from her son's bedside to her husband's. Hoping to give her husband time to recover, she paid a local man to serve as Joseph's substitute in the militia, meaning he would not have to serve out the remainder of his tour. Despite Lydia and the Ray family's nursing care, Joseph died by New Year's Day, 1781.

Tragedy struck the Ray home for a third time in February 1781 when the British army, en route to Guildford Courthouse, camped nearby. Although she resisted the soldiers' plundering her homestead and taking her cattle, Lydia had to prioritize her children's safety. Lydia gave birth to her fifth child that month while enemy troops still occupied her home. Lydia's son George later recalled that the British had stolen or destroyed nearly everything on their farm save Lydia's bed and nursery, another testament to Lydia's devotion to her family.

The War Comes Home: Mary Yarborough

Mary Yarborough's signature mark. Courtesy of National Archives.

After marrying Randolph Yarborough in March 1781, Mary Bailey moved from her family farm in southern Virginia to her husband's home in Halifax, North Carolina. The Yarborough’s honeymoon phase was cut short when General Charles Cornwallis and the British army marched into Halifax.

A private in the local militia, Randolph marched into battle while Mary fled into the countryside for safety. In attempting to defend the city, Randolph was shot in the chest, the bullet exiting near his spine. With Randolph's militia unit seriously outnumbered, the British occupied Halifax for several days.

A British surgeon extracted the bullet from Randolph's spine. Mary rushed back to Halifax and remained by her husband's bedside until he recovered. With no formal military hospital, the militia discharged Randolph when he was injured, leaving him to recover (or not) entirely independently. Randolph, like so many men wounded during the war, depended on his wife for nursing care. Despite the location of the wound, Randolph made a full recovery and rejoined the militia. Randolph carried a scar for the rest of his life, but it was a life he might not have had without Mary's nursing care.

- Ida Cohen Selavan, "Nurses in American History: The Revolution," American Journal of Nursing, 75:4 (April 1975) 592-594; "Healing Heroines," American Battlefield Trust, 7 September 2023 https://www.battlefields.org/learn/head-tilting-history/healing-heroines (accessed 10 January 2024); Blake McGready, "Abigal Hartman Rice, Revolutionary War Nurse," Journal of the American Revolution, 28 November 2016 https://allthingsliberty.com/2016/11/abigail-hartman-rice-revolutionary-war-nurse/ (accessed 10 January 2023).

- William A. Graham, General Joseph Graham and His Papers on North Carolina Revolutionary History (Raleigh: Edwards & Broughton, 1904) 64.