Sowing the Seeds: Women as Farmers during the American Revolution

Some historians have called the American Revolution a “Farmer’s War” due to the many yeoman farmers and poor laborers who filled the ranks of the Patriot army.1 The concept of a “Farmer’s War,” however, should also highlight the critical role women played through their efforts planting, cultivating, and harvesting crops at home. This agrarian work at home was just as essential to the war effort as that of militiamen. While men were away in service, women’s efforts in the fields fed their own families and the Patriot army.

"She was thereby compelled... to complete and finish the cultivation of the growing crop."

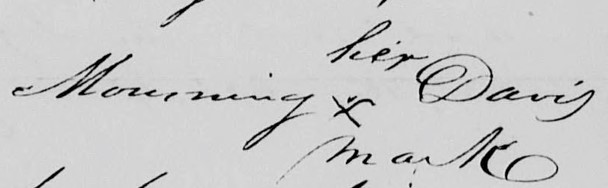

-Application for a Widow's Pension from Mourning Davis, 4 September 1843

"She and her negro woman were endeavouring to sow oats it was in the Spring."

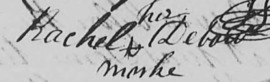

-Application for a Widow's Pension from Rachel Debow, 1 July 1837

"She with the help of their little Children made two Crops during her husbands absence "

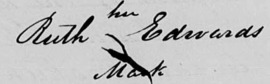

-Application for a Widow's Pension from Ruth Edwards, 31 October 1844

"He does know that his Wife made the Crops... & did nearly all the work in the field."

-Application for a Veteran's Pension from William Guest, 9 March 1835

"She had to work in the field in her husbans place."

-Application for a Widow's Pension from Sarah Jenkins, 14 March 1842

"She had to plow for her father while her Brother was in the army."

-Affidavit of Mary Yarborough in support of a Pension Claim for John Bailey, 20 June 1825

In respect of men’s duties at home during the harvest season, North Carolina Militia regiments often drafted men for a term of three or nine months. In reality, farming was a year-round obligation, and the many tasks of farm life could not wait for men to return home from the service to fulfill them.2 Women who had previously assisted in farm responsibilities alongside their husbands, brothers, and fathers now found themselves as independent farm managers with families, armies, and the American economy dependent on their success.

Although not subjected to military service, farming women were not immune from the threats of war. Women might carefully nurture a growing crop only for the army to appear at their doorstep at harvest time and seize it. Despite these many challenges, not only did women manage to keep their families and homesteads running, but they also cultivated and nurtured grain crops and livestock that fed the Patriot army.3 Through an informal system of cooperation, rural women relied on one another and managed their homesteads. Below are some examples of how some North Carolina women undertook new responsibilities on the farm during the Revolutionary War.

Engraving of a woman milking a cow. Aside from farming crops, women were also responsible for caring for the livestock. Courtesy of New York Public Library.

North Carolina Widows in Their Own Words

Called to Service: Mourning Davis

A resident of Johnston County, Mourning Pilkinton was about seventeen years old when she married John Davis in 1778. A year later when John enlisted in the 3rd North Carolina Regiment of the Continental Line, Mourning took on the responsibility of cultivating and harvesting their 300-acre plot of land.4 For the following two years, Mourning was the family farm manager, growing crops such as potatoes, carrots, squash, and cucumbers.

Mourning Davis' signature mark on her pension application. People who were otherwise illiterate often signed their documents with an X or a mark. Courtesy of National Archives.

Farming Under Fire: Rachel Debow

Rachel Debow's signature. Courtesy of National Archives.

Rachel Rogers was no stranger to managing a farm when she married Frederick Debow in Caswell County in 1777. Growing up in Orange County, Rachel had often participated in the yearly harvests at her parents' orchard, where the community gathered together to help pick apples and boil them into cider.

By the time her husband Frederick joined the service, Rachel was well prepared for the many duties of being a rural farmwife. In her pension application, she recalled how she and an unnamed African American woman she enslaved were sowing a crop of oats near Cane Creek when they heard the distinct sound of cannon fire in the distance, likely stemming from a skirmish around the Battle of Guilford Courthouse. Despite the sounds of violence in the distance, they continued to plant their crop, for there would be nothing to eat the following winter if they did not get the family's fields seeded soon enough.

A Family Affair: Ruth Edwards

Throughout the course of the American Revolution, Ruth Edwards' husband John was away performing military service for fifteen months. Unable to depend on her husband for support, Ruth found herself left at home with four children, one still an infant and the eldest no older than seven years old. In spite of her circumstances, Ruth made do and taught her oldest son William how to hold the plow while she directed the team of livestock. During John's absence, Ruth and her children seeded and harvested two years worth of crops.

Ruth Edwards' signature mark. Courtesy of National Archives.

Single Motherhood: Anna Guest

Anna Guest's signature mark. Courtesy of National Archives.

In 1780 Anna Guest found herself alone on her farm on the Yadkin River in Wilkes County. Holding Squire, her newborn infant, Anna had to tend to her growing crop through the spring and summer while her husband William was away in service with the Wilkes County Regiment of the North Carolina Militia. Although William came home occasionally, Anna frequently went without seeing him for months at a time. As Anna later reflected in her pension application, she "had to work and make a support... and do the best she could."

A Community Task: Sarah Jenkins

Prior to the war, the intensive nature of farm labor had often united many farm families within a community. When the time of year came for plowing or reaping, families like the Jenkinses and their neighbors helped one another in a spirit of cooperation, gathering together at each other’s homesteads to help thresh wheat or pick fruit from the orchards. These collaborative community networks became even more important during the American Revolution. While their husbands were away, neighborhood women like Sarah Jenkins assisted one another in the routine tasks of childrearing and farm maintenance. Not only was Sarah responsible for growing her own crops, but she also upheld her husband's promise that the Jenkinses would help tend to their neighbors' crops too.

Sarah Jenkins' signature mark. Courtesy of National Archives.

Filial Duty: Mary Yarborough

Mary Yarborough's signature mark. Courtesy of National Archives.

Mary Bailey was about seventeen when her older brother John came home with a soldier's uniform and told the family that he'd enlisted in the Continental Line. While John was away in service for the following three years, Mary's father depended on her to perform many kinds of manual labor on the farm including plowing the fields and harvesting the crops. All the while, Mary also helped care for her younger siblings.

When Mary married Randolph Yarborough in 1781, she moved to her own farmstead in Halifax County, North Carolina. There, she continued to assume a lead role in farm management while her husband was away in service and, later, recuperating from wounds he sustained during the war.

- Allan Kulikoff, From British Peasants to Colonial American Farmers (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2000) 264.

- Mary Beth Norton, Liberty's Daughters: The Revolutionary Experience of American Women, 1750-1800 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1980) 36. Corn crops need thinning as they grow, and grain crops such as oats require processing after harvest time to preserve them. Even simple routine tasks such as watering, weeding, and removing pests from the crops all had to be done by hand, compounding the time needed. Ed Shultz, "Weedkiller," Colonial Williamsburg, 22 May 2021 https://www.colonialwilliamsburg.org/learn/living-history/weedkiller/ (accessed 11 December 2023).

- In one case a North Carolina woman offered some American soldiers some food, only to find her home the scene of a skirmish when loyalist troops arrived and demanded the food from the hungry patriots. More commonly soldiers robbed defenseless families of their crops and livestock. Sometimes the military paid for the goods they seized, but merely with highly-inflated paper currency or with a promise to pay later, both of which were next to useless when women needed to feed their families. Cynthia Kierner, Southern Women in Revolution, 1776-1800: Personal and Political Narratives (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1998) 17-18; Kierner, The Tory's Wife: A Woman and Her Family in Revolutionary America (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2023) 154; Elizabeth Fries Ellet, Women of the Revolution (New York: Baker and Scribner, 1848) 1:16.

- Johnston County Land Grant Files, No. 2115, State Archives of North Carolina, S.108.754, frame 220 https://nclandgrants.com/frame/?fdr=956&frm=220&mars=12.14.78.2095 (accessed 12 December 2023).