Project Apollo

American astronaut Edwin "Buzz" Aldrin became the second man to step foot on the Moon on July 21, 1969. Courtesy NASA.

Project Apollo’s ultimate goal—to put a man on the Moon and return him safely to Earth—was achieved just eight years after President John F. Kennedy’s challenge, a testament to American ingenuity and perseverance.

Between 1969 and 1972, twelve men walked on the Moon. This feat, however, could not have been achieved without the support of hundreds of thousands of Americans from a wide range of professions. North Carolina engineers, mathematicians, manufacturers, scientists, and aviators all contributed greatly to the successes of Project Apollo.

North Carolina State Contracts

Medicine, mission patches, and special alloys—the contributions of North Carolina manufacturers, though limited in number, cannot be overlooked. From 1961 to 1972, when the final Apollo mission was flown, NASA awarded state-based contractors more than $23,000,000 in contracts.

This Apollo 16 mission patch was made by Buncombe County-based A-B Emblem. Courtesy North Carolina Museum of History.

North Carolina-based Burroughs Wellcome provided several key medicines for Apollo missions, including Neosporin (an antibiotic ointment), Marezine (for motion sickness), and Actifed (for sinus/ nasal congestion). Courtesy North Carolina Museum of History.

Monroe-based Allvac Metals Company used turbines like this one to produce Renee 41, a special alloy used in the production of the heatshields for Gemini and Apollo spacecraft. The heatshield protected the astronauts from the intense heat created by the spacecrafts' re-entry into the Earth's atmosphere. Courtesy North Carolina Museum of History.

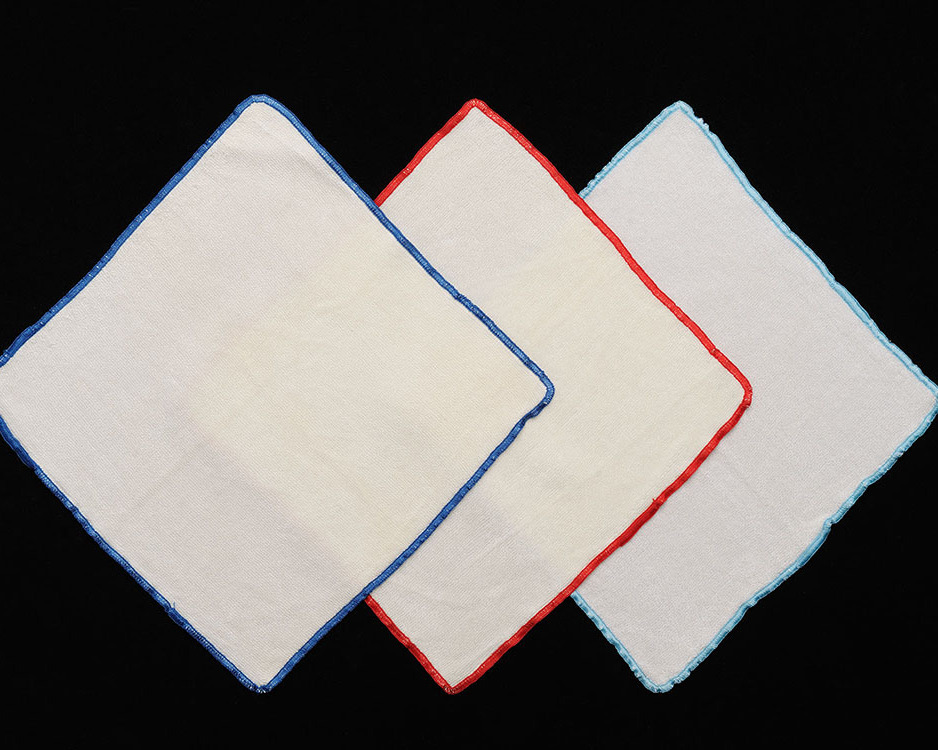

Lightweight, compact washcloths made by the School of Textiles at North Carolina State University accompanied astronauts on Gemini and Apollo missions. Courtesy North Carolina Museum of History.

Corning Glass produced several key components for American spacecraft, including the window glass through which astronauts caught their first glimpses of the Moon and the Earth from space. Here in North Carolina, specifically Raleigh, Corning facilities manufactured glass capacitors and memory banks used in Apollo-era spacecraft. Courtesy North Carolina Museum of History.

Batteries made by Exide Missile powered pyrotechnic systems in the command, service, and lunar modules. Parachute deployment, mid-course maneuvers, ascent and descent of the lunar lander—just a few of the processes powered by batteries made in Raleigh. Courtesy North Carolina Museum of History.

From Apollo 13 up to the present, A-B Emblem, a company based in Weaverville (Buncombe County), has been the sole provider of official NASA mission patches. Courtesy North Carolina Museum of History.

As head of the computing unit at Muroc, Person County native Roxanah Yancey supported Chuck Yeager's sound-barrier-breaking 1947 flight by, according to NASA, "identifying traces on film, marking time to coordinate all data recordings and reading film deflections before converting them into engineering units." She went on to become an aerospace engineer and studied the effects of speeds Mach 6 and greater on aircraft. Courtesy NASA.

Human Computers

In the early days of NASA, people—not devices that provided instant results—performed the mathematical calculations necessary to put a man in space. Women, including some from North Carolina, comprised the majority of these “calculators,” or “computers,” taking on work originally performed by engineers. Their tools of the trade were not electronic, or even necessarily electric; they were likely hand-manipulated slide rules, spring-loaded calculating machines, pencils, and paper.

By the time of Apollo, the arrival of computing machines—the beginnings of today’s computers—had revolutionized their work, and many women transitioned into computer programming.

Mary Hedgepeth (standing, far left), of Cleveland County, and Roxanah Yancey (standing, third from left), of Person County, both worked as computers for NASA’s precursor—the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, or NACA—at Muroc Air Force Base in California. They are pictured here with fellow computers in 1949. Courtesy NASA.

North Carolina natives Roxanah Yancey, center, and Mary Hedgepeth, far left, computed data in support of high speed flight studies for the NACA Muroc Flight Test unit. Courtesy NASA.

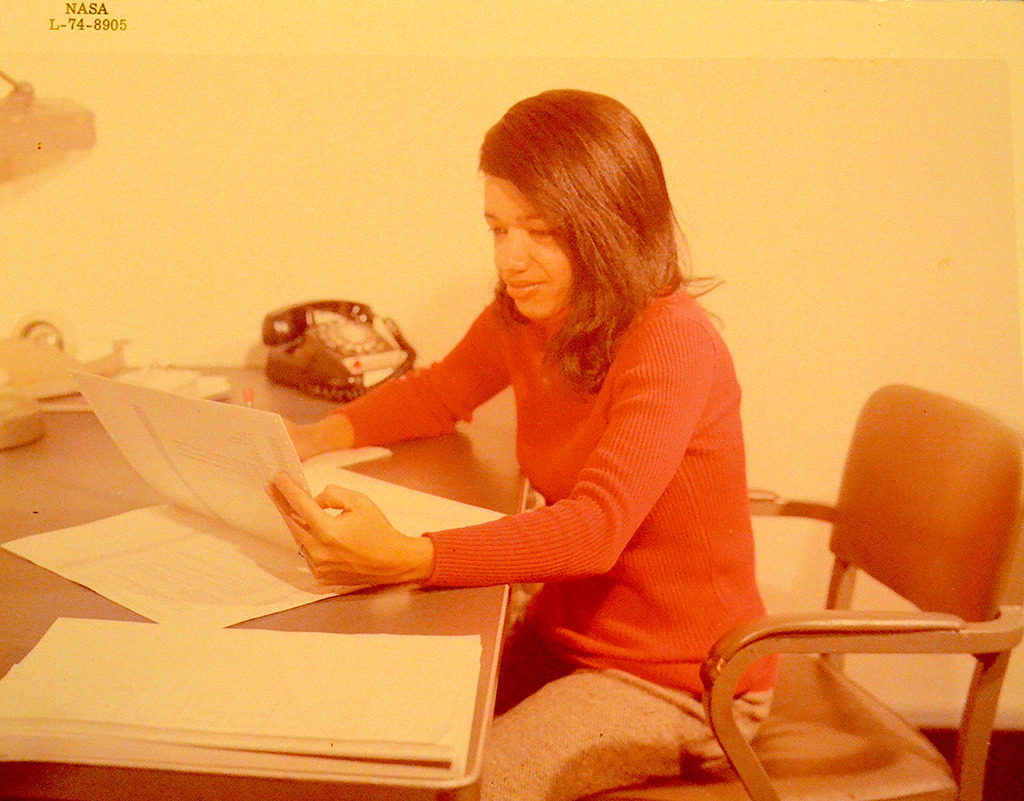

Monroe (Union County) native Dr. Christine Darden—shown here at Langley Research Center in 1974—began her NASA career as a computer in 1967. Soon after her arrival, she and her colleagues transitioned into computer programming and wrote programs that could perform the necessary calculations. Courtesy Dr. Christine Darden.

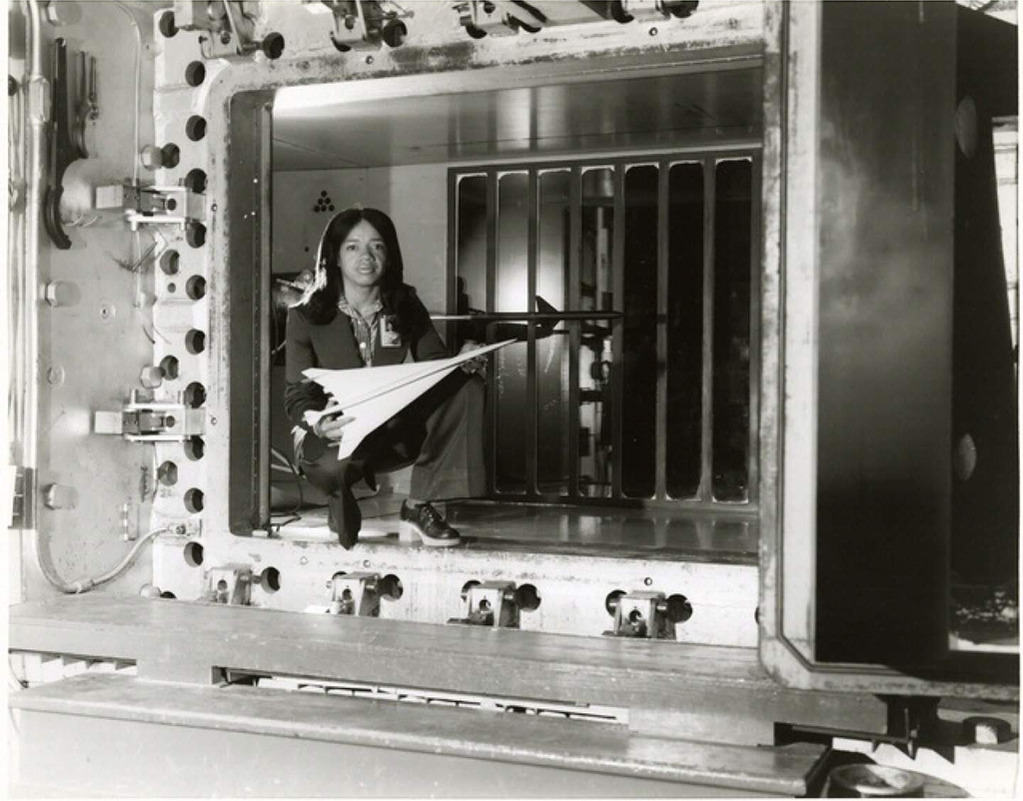

In 1972, Dr. Christine Darden transferred to an engineering section that was charged with minimizing sonic booms. For 20 years, she specialized in this research, moving us closer to a more commercially friendly, low-boom aircraft design. Dr. Darden concluded a distinguished forty-year career with NASA in 2007 and is recognized today as one of the world’s foremost experts on supersonic wing design and sonic boom mitigation. Courtesy National Air and Space Museum Archives, Smithsonian Institution.

An Army of Contractors

Not everyone who supported NASA’s efforts to go to the Moon worked for the agency directly. Companies representing a variety of fields from all around the country entered into contracts with the federal government to supply NASA with specialized knowledge and technology. At the height of the space race, the number of contracted employees reached into the hundreds of thousands. It remains a mystery just how many North Carolinians helped put a man on the Moon without ever brandishing the NASA logo.

In 1966, Arthur B. "Art" Case, who later retired to North Carolina, was considered to be one of the “five…most important IBMers” at Cape Kennedy in Florida. From the relative safety of the blockhouse, Case and his fellow IBM test conductors were responsible for the final checks of the launch control equipment in preparation for vehicle liftoff. It was a high-pressure, high-stakes job, an environment in which Case seemed to thrive. As manager of Complex 34 during the Saturn IB program, Case witnessed firsthand both the tragedies and triumphs of the American space program.

North Carolinian Arthur Case supported America's race to space as a contractor from IBM. Courtesy Steve Case.

Art Case was on-site when the Apollo 204 (later renamed Apollo 1) fire broke out. Former colleagues remember how he immediately flew into action, running through a series of switches and panels to shut down systems faster than it had ever been done before. Courtesy Steve Case.

Art Case, standing right, assists a colleague at Kennedy Space Center's Complex 34. Courtesy Steve Case.

Case's first major triumph came on February 26, 1966, with the successful launch of Apollo 201, for which he served as chief test conductor. The primary goals of the unmanned, suborbital flight were to test both the Saturn 1B launch vehicle and the heat shield of the spacecraft. Courtesy NASA.

Art Case, far right, was a manager with IBM at Kennedy Space Center during the Apollo program. Courtesy Steve Case.

Following the successful flight of Apollo 7, several IBM team members celebrated at a local bar. The establishment had the strange custom of cutting off the neckties of their patrons. The severed ties were all collected, arranged to spell "Apollo 7," framed, and awarded to Art Case for his leadership during the mission. Courtesy Steve Case.

As the space race wound down following the success of the Apollo 11 lunar landing, IBM began reassigning employees to other stations around the country. Such a reassignment brought Art Case (center) to North Carolina. Courtesy Steve Case.

Charlotte-born Charles Duke became the youngest person to walk on the Moon on April 21, 1972. Courtesy NASA.

Charles Duke and Apollo 16

Charles M. “Charlie” Duke is the only man with North Carolina ties to have walked on the Moon. Though born in Charlotte, Duke was raised across the state line in his parents’ home state of South Carolina. He went on to graduate from the United States Naval Academy and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In 1966, at the age of thirty, Duke was one of nineteen men selected for Astronaut Group 5.

In 1972, Duke served as the lunar module pilot for the Apollo 16 flight. Mission commander John Young accompanied Duke to the lunar surface. Together, Duke and Young collected samples and conducted a series of experiments in the Descartes Highlands, a crater-pocked region on the near side of the Moon, from April 21 through 23, 1972. The team remained on the lunar surface for seventy-one hours.

Duke served as a member of the astronaut support crew for Apollo 10 and as CAPCOM—the main point of contact between spacecraft crew and mission control—for Apollo 11. Courtesy NASA.

Some training for the Apollo 16 flight occurred on the property of Kennedy Space Center. Here, Duke practices deploying a core tube with a hammer in March 1972. Courtesy NASA.

Duke became the youngest person to walk on the Moon on April 21, 1972. Courtesy NASA.

During their seventy-one hours on the Moon, Duke and fellow astronaut John W. Young collected samples and conducted a series of experiments in the Descartes Highlands, a crater-pocked region on the near side of the Moon. Courtesy NASA.

Geological Investigation

Due to a medical condition, UNC Chapel Hill alumnus and professor Dr. Joel S. Watkins was declared medically ineligible for NASA’s scientist-astronaut program—the same program that put fellow geologist Harrison Schmitt on the Moon. Undeterred, Dr. Watkins sought alternative means of supporting geological and geophysical study of the lunar subsurface.

In June 1964, Dr. Watkins and colleagues from the Astrogeology Branch of the US Geological Survey conducted a geological field school at the Philmont Scout Ranch in northern New Mexico. There, they trained Apollo astronauts in geologic mapping, field note documentation, and how to analyze subsurface structure using magnetometers, seismometers, and gravimeters.

And though he could not make the trip through space himself, Dr. Watkins found another way to contribute to man’s investigation of the Moon’s physical makeup. During Apollos 14, 16, and 17, astronauts deployed devices developed by Watkins to measure moonquakes. The results of those experiments are still being analyzed today, to deepen our understanding of the Moon’s composition.

Geologist Joel S. Watkins devised several means of seismographic investigation of the Moon's composition for Apollo-era astronaut crews. Courtesy Catherine Barker.

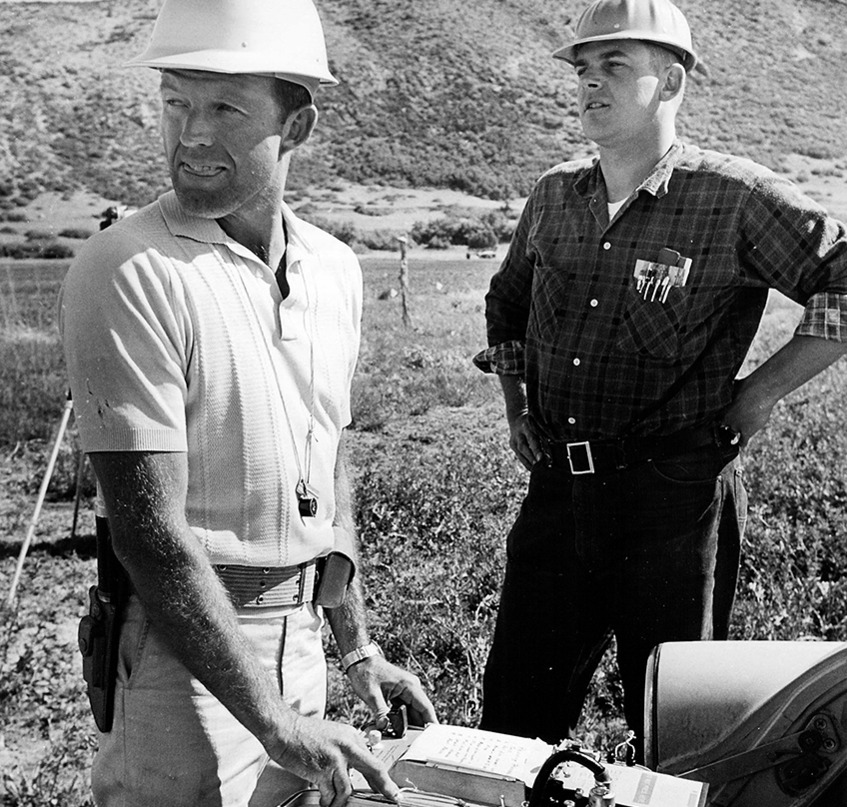

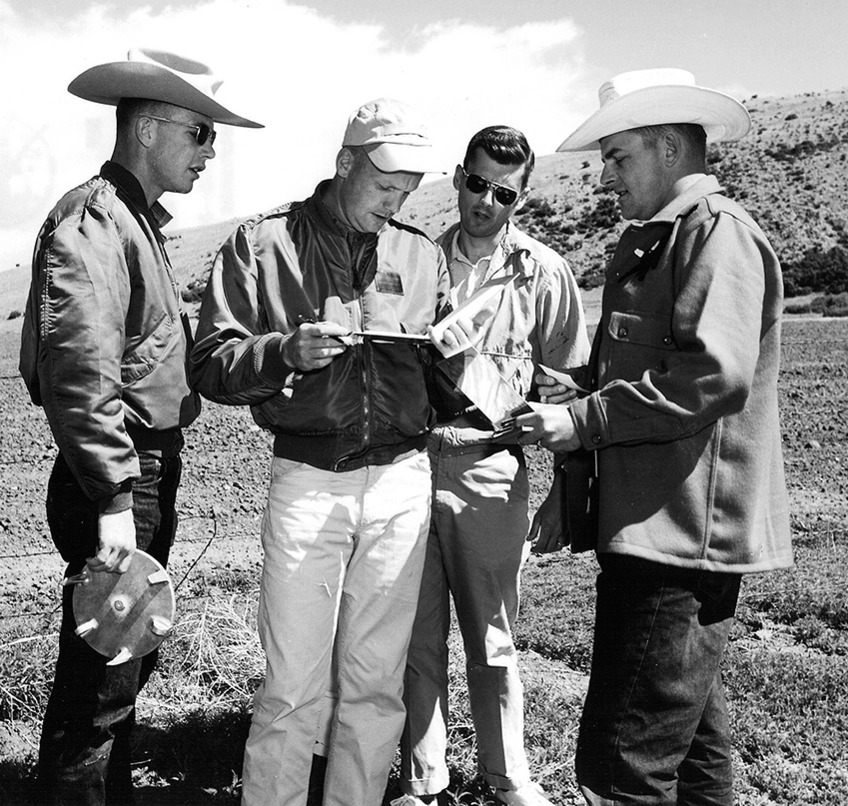

Dr. Watkins observes astronaut Gordon Cooper's operation of a piece of equipment during the June 1964 geological field school at the Philmont Scout Ranch. Courtesy NASA.

Dr. Watkins, right, discusses gravity meter data with astronauts (from left to right) David Scott, Neil Armstrong, and Roger Chaffee in June 1964. During the course of the field school, Dr. Watkins built up quite a rapport with the astronauts. On the last night of the school, he and fellow USGS colleague Norman "Red" Bailey short-sheeted several of the astronauts' beds before going to sleep. Courtesy NASA.

Astronauts Alan Shepard, right, and Edgar Mitchell, left, practice using a piece of seismographic equipment known as a "thumper" that was designed by Dr. Watkins. Courtesy NASA.

In a photograph taken from the Modularized Equipment Transporter, astronauts Edgar Mitchell (foreground, left) and Alan Shepard can be seen deploying seismographic equipment developed by Dr. Watkins on the lunar surface during the Apollo 14 mission. Courtesy NASA.

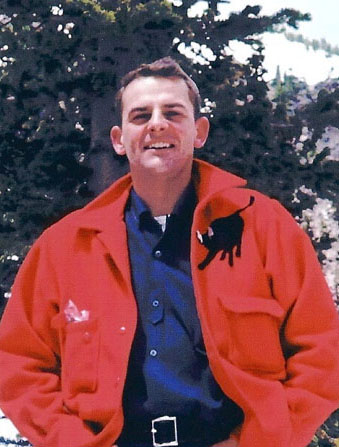

Philadelphia-born Richard J. Barrett moved to North Carolina as a toddler, spending his childhood years in Canton (Haywood County) and Asheville (Buncombe County). Following graduation from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, he entered active service with the US Navy and completed a tour of the Gulf of Tonkin during the Vietnam War. Courtesy Richard J. Barrett.

Astronaut Recovery

After Virgil I. “Gus” Grissom’s Liberty Bell 7" capsule sank—and he nearly drowned—during the second manned Mercury mission, NASA worked closely with military partners to overhaul recovery protocol. As a member of Helicopter Anti-Submarine Squadron Four (HSC-4), Lt. Richard J. Barrett—who grew up in Asheville and Canton—contributed to the development of search and rescue procedures for early manned Apollo flights.

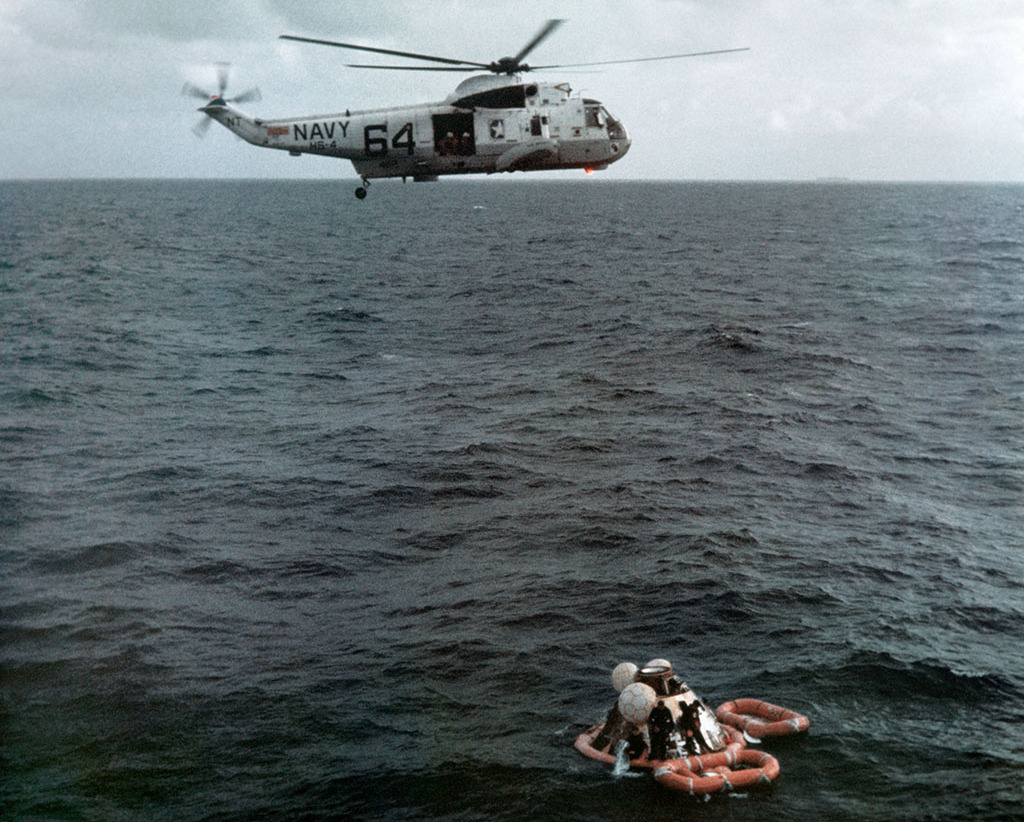

Though he participated in the recoveries of Apollos 8 and 10, it was his involvement in helping to develop and execute search and rescue procedures for Apollo 11 that is perhaps most firmly etched in his mind. Piloting helicopter 64 that July day in 1969, Lieutenant Barrett skillfully and expertly dropped Navy swimmers and important gear next to the bobbing Apollo 11 capsule.

As pilot of helicopter 64, Lieutenant Barrett was responsible for transporting a Navy swim team to the splashdown site of the Apollo 11 capsule. Courtesy Richard J. Barrett.

Lieutenant Barrett stayed on-scene as the swimmers attached a flotation collar to the capsule, inflated rafts, and helped the astronaut crew into contamination suits. Courtesy Richard J. Barrett.

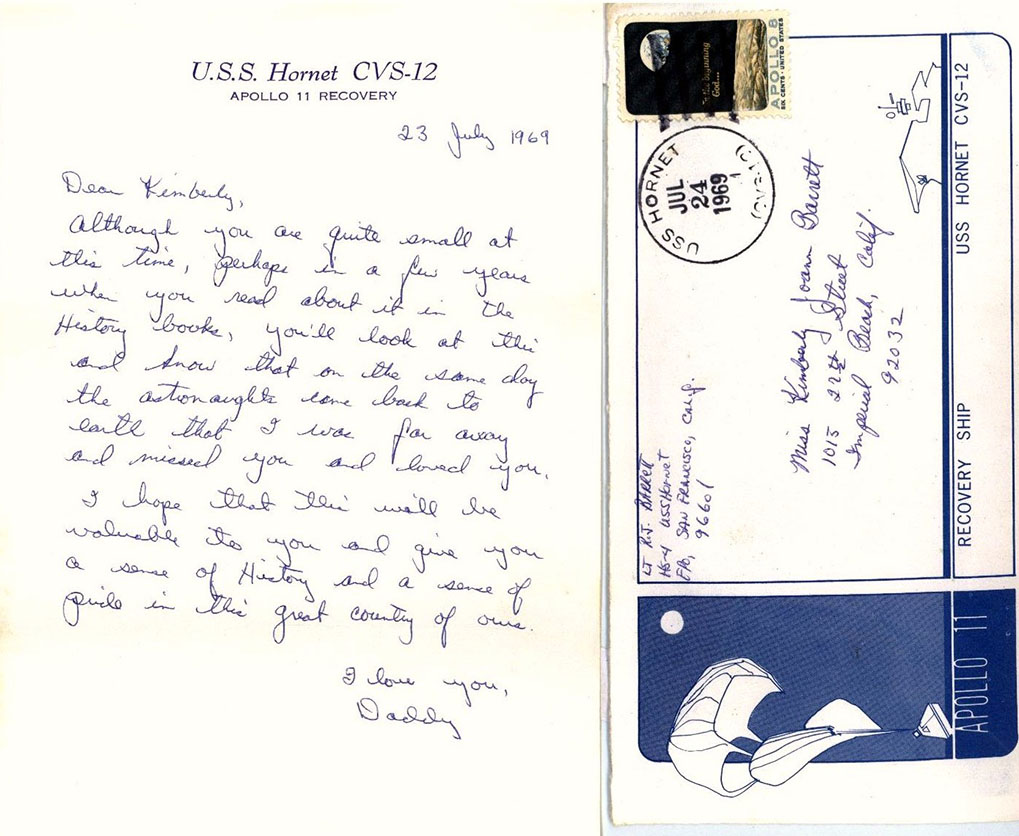

With the Apollo 11 recovery mission looming just one day out, Lieutenant Barrett sat down and penned a sweet, short letter to his then two-month-old daughter Kimberly. Courtesy Richard J. Barrett.

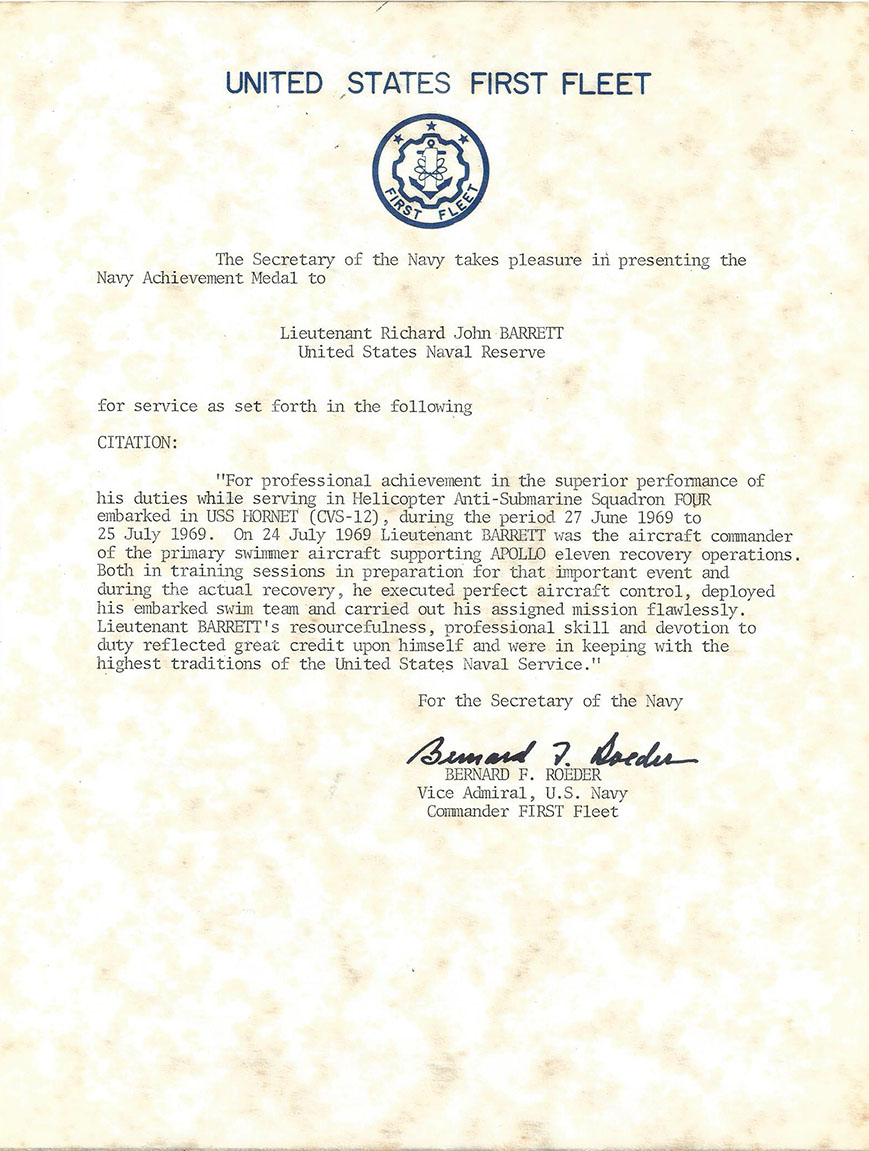

Lieutenant Barrett's Navy Achievement Medal reads, in part, "Both in training sessions…and during the actual recovery, he executed perfect aircraft control, deployed his embarked swim team and carried out his assigned mission flawlessly. Lieutenant Barrett's resourcefulness, professional skill and devotion to duty reflected great credit upon himself and were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service." Courtesy Richard J. Barrett.

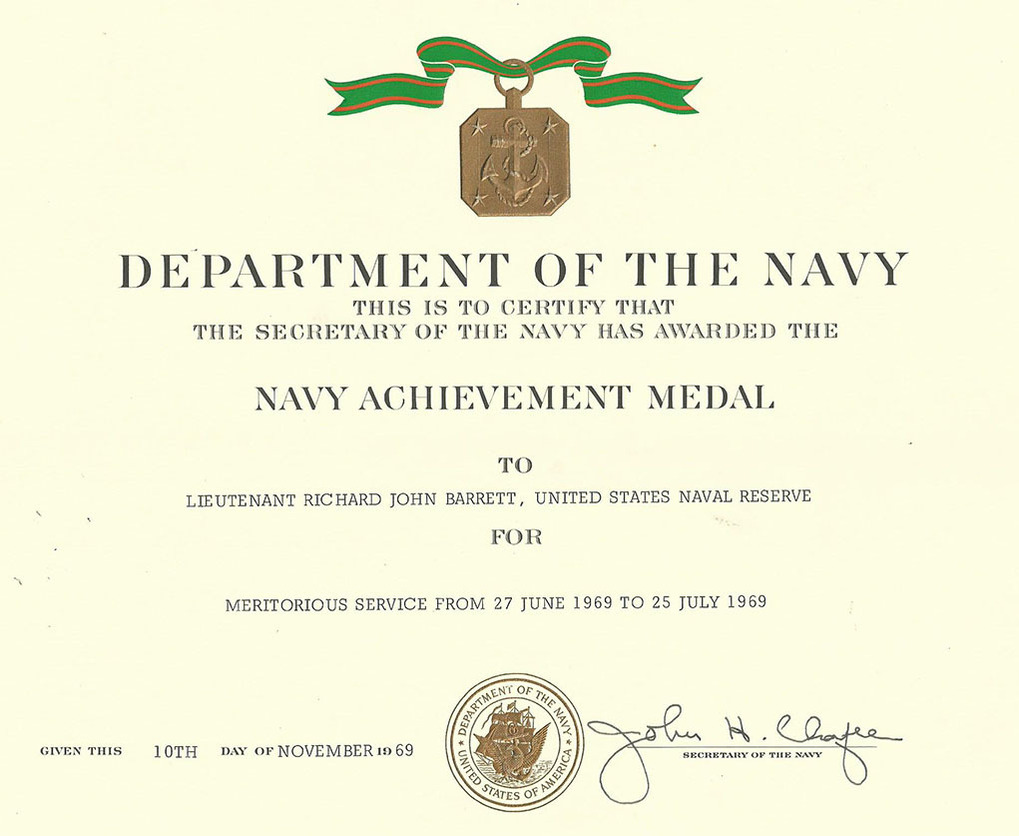

For his service during the Apollo 11 recovery, Lieutenant Barrett received a Navy Achievement Medal and this accompanying certificate. Courtesy Richard J. Barrett.

.jpg)