Beyond Apollo

Christina Koch is the most recent person from the Tar Heel State to make the trip to space. Here she is aboard the International Space Station on March 18, 2019. Courtesy NASA.

With the arrival of the space shuttle program, North Carolinians finally started seeing their own among the high-profile astronaut crews, a trend that continues to this day.

All around the country, the successes of the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs played out in real time on living room television screens. For the first time in history, a generation came to maturity in a world in which space travel was considered an ordinary part of human existence. Young boys and girls began imagining themselves not just as Crayola-colored doctors, soldiers, and presidents, but also as astronauts, as brave explorers of a new frontier. The influences of NASA’s golden era on the state’s citizenry can still be found today.

First Astronaut from North Carolina

William E. Thornton is arguably North Carolina’s first homegrown astronaut. (Though Charlotte-born Charlie Duke’s selection for the astronaut program preceded Thornton’s by seventeen months, Duke was raised in his parent’s home state of South Carolina.) Born and raised in Faison, Thornton attended UNC Chapel Hill, where he received a bachelor’s in physics in 1952 and a doctorate in medicine in 1963. During his time with the U.S. Air Force, Thornton learned to fly jet aircraft and completed Primary Flight Surgeon’s training, setting a solid foundation for his career in space medicine research.

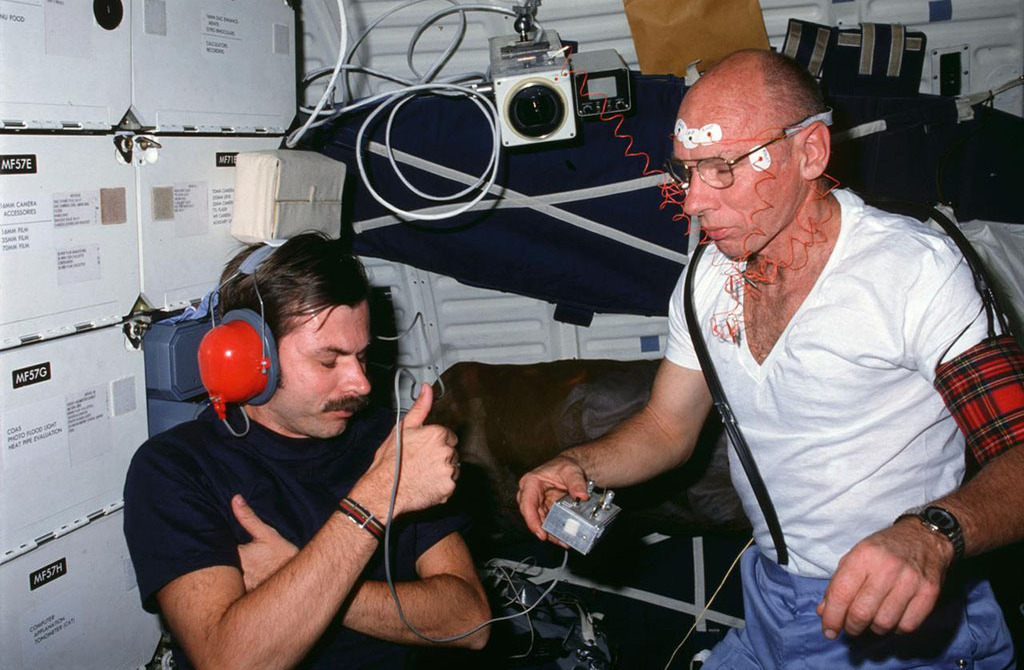

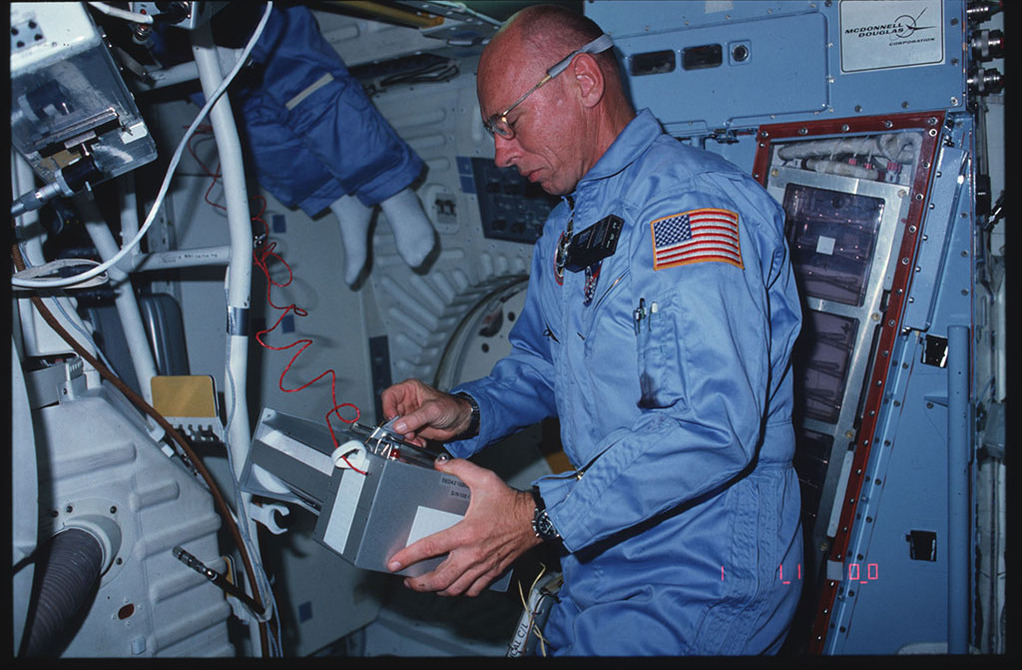

NASA selected Thornton as a scientist-astronaut in August 1967. During his twenty-six years with the nation’s preeminent space program, Dr. Thornton focused his work on the effects of space on the human body, particularly a condition known as “space adaptation syndrome.” To counteract the effects of weightlessness, Dr. Thornton developed several monitoring and exercise devices. He is perhaps best known for inventing a treadmill that can be used in space to help prevent muscle atrophy. The highlights of his career, however, came in the mid-1980s when he crewed space shuttle missions STS-8 and STS-51B aboard the Challenger, logging a cumulative 313 hours in space.

North Carolina native William E. Thornton was selected as a scientist-astronaut in August 1967. Courtesy NASA.

In the summer of 1972, Dr. Thornton took part in the Skylab Medical Experiment Altitude Test (SMEAT). SMEAT sought to test medical equipment and gather data in preparation for Skylab. Here, Dr. Thornton (standing) is preparing Karol J. Bobko for an experiment that tested the effects of negative pressure on the lower body. Courtesy NASA.

Astronaut Dale Gardner assists Dr. Thornton in conducting an audiometry test aboard Challenger during STS-8 in 1983. Courtesy NASA.

Dr. Thornton took his first space flight aboard the shuttle Challenger on mission STS-8 in 1983. Courtesy NARA.

Dr. Thornton's second and final space flight occurred in 1985. This image captures him in the pilot's station of the flight deck of the space shuttle Challenger. Courtesy NARA.

Thornton wore this blue NASA flight suit during the Spacelab 3 mission in 1985. Courtesy North Carolina Museum of History.

Dr. Thornton monitors fellow astronaut Guion Bluford's use of the treadmill he designed for use in space aboard the shuttle Challenger in 1983. Courtesy NARA.

Over the course of his career, Wadesboro native and NASA engineer John Kiker made several iconic contributions to the American space program. Courtesy NASA.

Shuttling the Shuttle

One of the more interesting facts about the space shuttle is that it essentially is a big glider. The vehicle had no real thrust capabilities of its own, relying instead on the Saturn booster system to escape Earth’s gravity. Though the shuttle could land much like a plane on a runway, it could not lift off from a runway under its own power. NASA officials faced one huge question: how do we shuttle the shuttle between the landing and take-off sites?

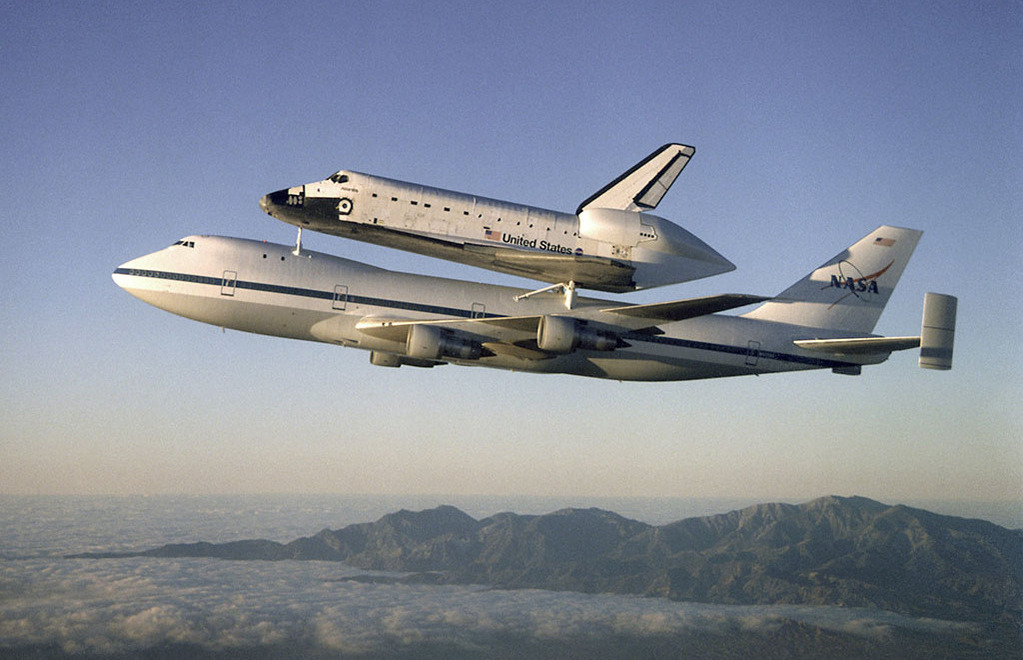

Wadesboro native and NASA engineer John W. Kiker had the answer. Using scaled, remote-controlled models, Kiker set about proving that the shuttle could be safely and more affordably transported by mounting it to the back of a modified Boeing 747. The NASA community was skeptical at first, but they gave Kiker the room he needed to develop the idea. Kiker’s “piggyback” plan became reality on February 18, 1977, when the shuttle Enterprise was mounted atop a 747 and carried into the sky for its first “flight.”

Two specially modified 747s, known as the Shuttle Carrier Aircraft, ferried shuttle vehicles through the entirety of the program. The final piggyback flight occurred in 2012, when one of the planes carried the Endeavour from Florida to California for retirement.

John Kiker's contributions to the American space program were not just limited to the development of the piggyback system. Early in his NASA career, Kiker and his colleagues designed the three-parachute landing system of the Apollo program. This image captures the parachute system in action during the return of the Apollo 16 crew. Courtesy NASA.

With the help of colleagues, Kiker (right) first tested his piggyback design with models. Using a 1/40th scale model of the space shuttle and a model airplane, Kiker evaluated flight control of the mated system and tested the separation of the two during a test flight in December 1975. Courtesy NASA.

Several full-scale tests of the piggyback system were conducted in 1977 at the Dryden Flight Research Center (now Armstrong Flight Research Center). Here, the shuttle Enterprise glides above its 747 carrier just moments after separation on September 13, 1977. Courtesy NASA.

Soon, piggyback flights became one of the most iconic sights of the shuttle era. Here, a 747 shuttles Atlantis back to Kennedy Space Center in 1998. NASA estimates that Kiker's design saved the government about $19 million every time a shuttle had to be transported. Courtesy NASA.

A Nation in Mourning

Beaufort native Michael J. Smith was just twenty-four when he watched Neil Armstrong take man’s first step on the Moon. Right then and there, he determined to become an astronaut. A meritorious career in the Navy followed, during which Smith learned to fly 28 different aircraft, flew 198 missions in Vietnam, and logged 4,868 hours of flight time.

In May 1980, he was accepted as an astronaut candidate and qualified as a shuttle pilot the following year. The call Smith long awaited finally came in 1985 when he was tapped to pilot the Challenger on its tenth mission. Tragically, the flight proved to be both Smith’s first and last. Just seventy-three seconds after launch on January 28, 1986, an O-ring seal in one of the Challenger’s two solid rocket boosters suffered a critical failure, leading to the disintegration of the shuttle over the Atlantic Ocean. The lives of all seven crew members were lost, including that of Mission Specialist Ronald E. McNair, a North Carolina A&T State University alumnus from South Carolina.

To date, Smith is one of twenty-four American astronauts to have lost their lives in the line of duty. In recognition of his sacrifice, he was posthumously awarded the Congressional Space Medal of Honor in 2004.

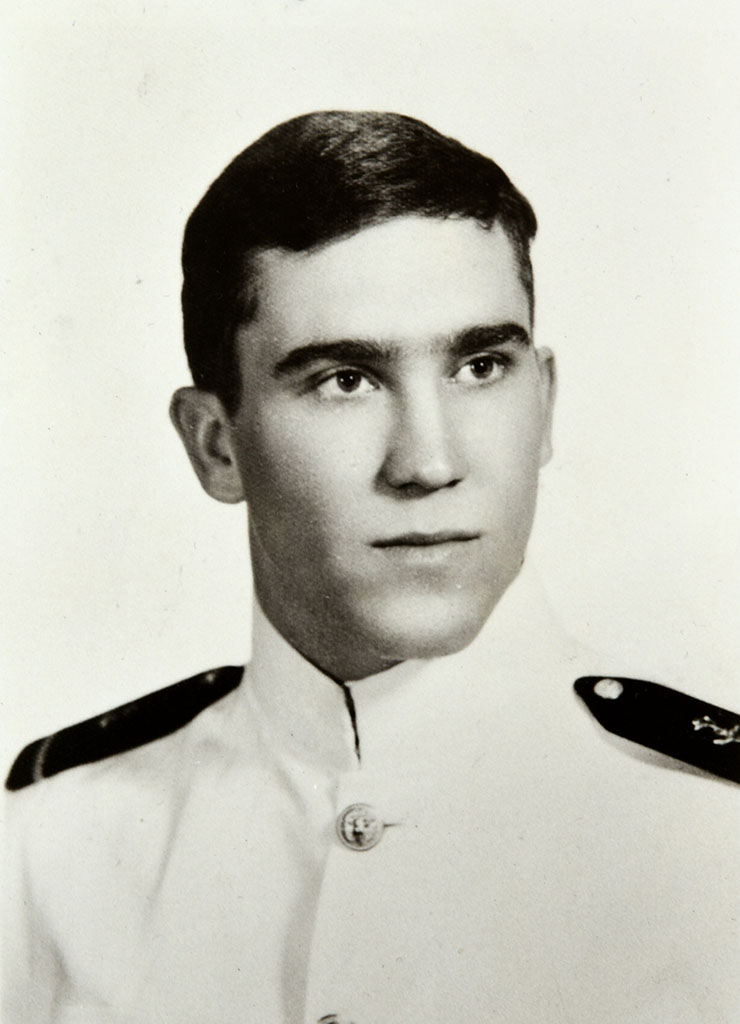

Official NASA portrait of Beaufort native Michael Smith, taken on January 8, 1981. Courtesy NASA.

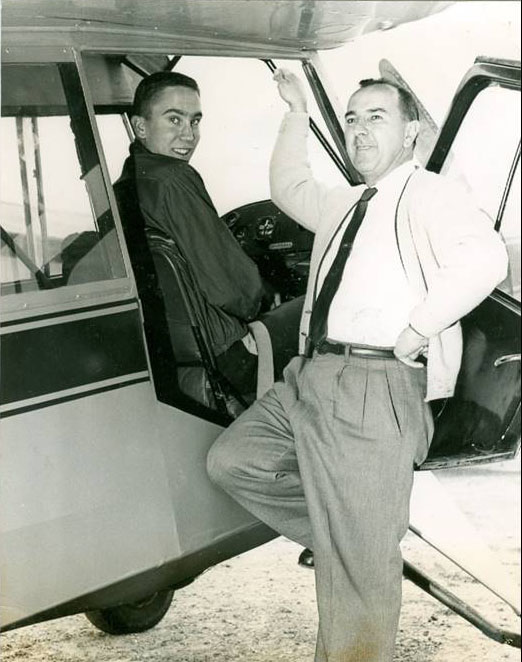

Few people pursue their dreams with a zeal and perseverance that could match Smith. At just sixteen years old, an age at which most teens are preoccupied with learning to drive, Smith took his first solo flight. He is pictured on that day in 1961 with his flight instructor Bob Burrows. Courtesy Smith Family.

On April 30, 1961, Mike Smith took his first solo flight, earning his pilot's license. In a letter to his friend Bobby, the sixteen-year-old farm boy from Beaufort could barely contain his excitement: "I went flying alright, I soloed!" Courtesy Smith Family.

Smith entered the United States Naval Academy in 1963. He graduated four years later, ranked 108 in his class of 893. Richard Purnell, an academy classmate of Smith's, later recalled that upon meeting him, one of the first things Smith told him was "I am going to be an astronaut."

Following his graduation from the Naval Postgraduate School, Smith went on to attend flight school, earning his wings in 1969. "Whenever I was conscious of what I wanted to do," Smith once said in an interview, "I wanted to fly. I can never remember anything else I wanted to do but flying."

In 1972 and 1973, Smith served as an attack pilot assigned to the USS Kitty Hawk during the Vietnam War, flying 198 missions before returning home to attend test pilot school at the Naval Air Test Center in Maryland. He is pictured here aboard the Kitty Hawk during his wartime deployment.

NASA selected Smith as an astronaut candidate in May 1980, about the time this portrait was taken. Following a year of training, Smith qualified as a shuttle pilot. The call he long awaited finally came in 1985 when he was tapped to pilot the Challenger on its tenth mission the following year.

Mike Smith absolutely loved to fly. As quarterback of his high school football team, he once called a timeout just to watch a plane fly overhead. Here he is post-flight (left, foreground), brandishing a huge grin, in September 1985. To his right are astronauts Barbara Morgan, Christa McAuliffe, and Francis Scobee. Courtesy NASA.

The space shuttle Challenger launched for its tenth mission on January 28, 1986. Seventy-three seconds into its flight, an O-ring seal in one of the solid rocket boosters failed, resulting in the loss of the vehicle and its crew. Courtesy NASA.

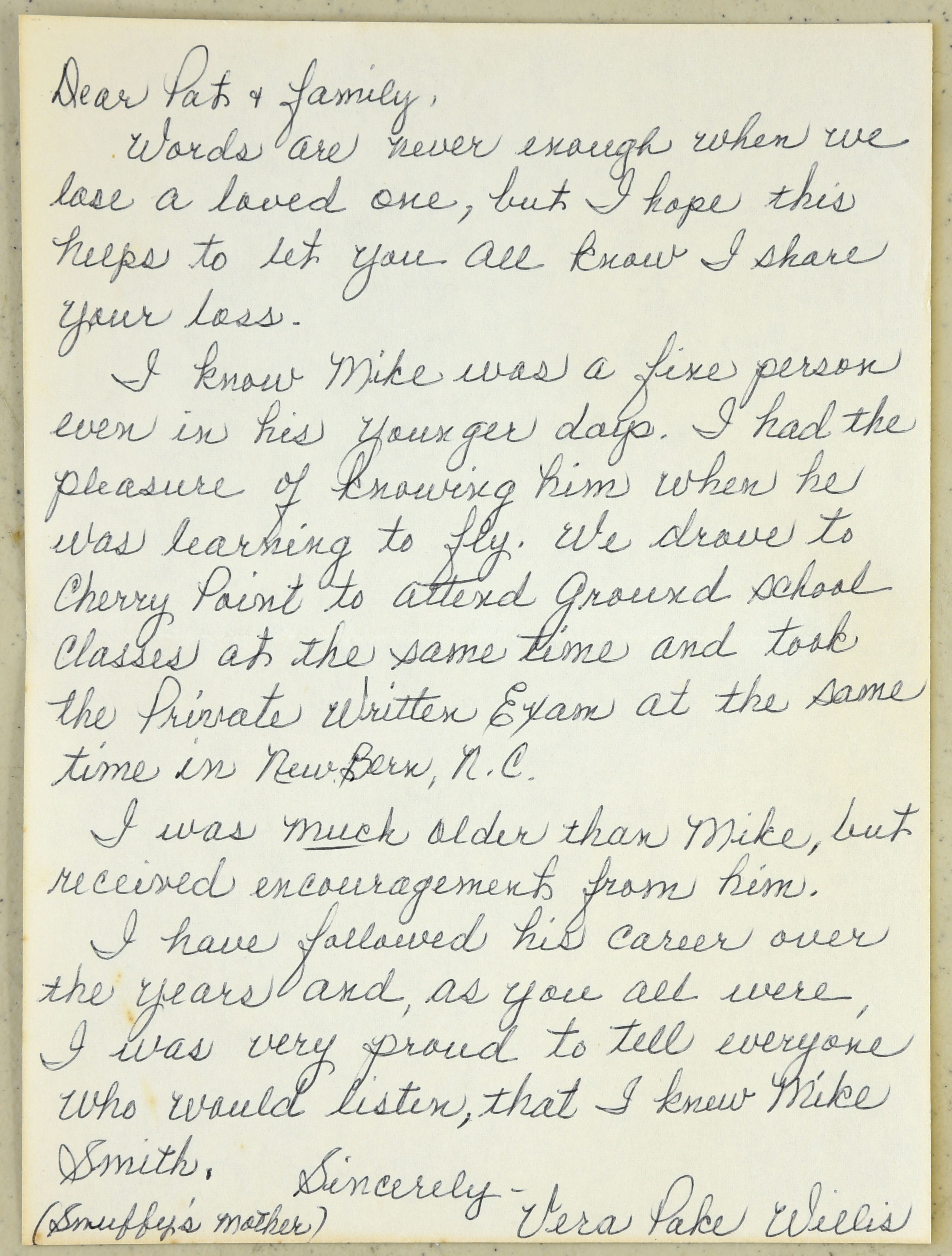

Following the accident, letters and cards poured in to Beaufort from across the nation. Sometimes the letters came from strangers, sometimes from friends and acquaintances of days gone by. One local resident wrote Mike's brother Pat to share the wonderful memories she had of knowing Mike when the two were learning to fly. Courtesy Smith Family.

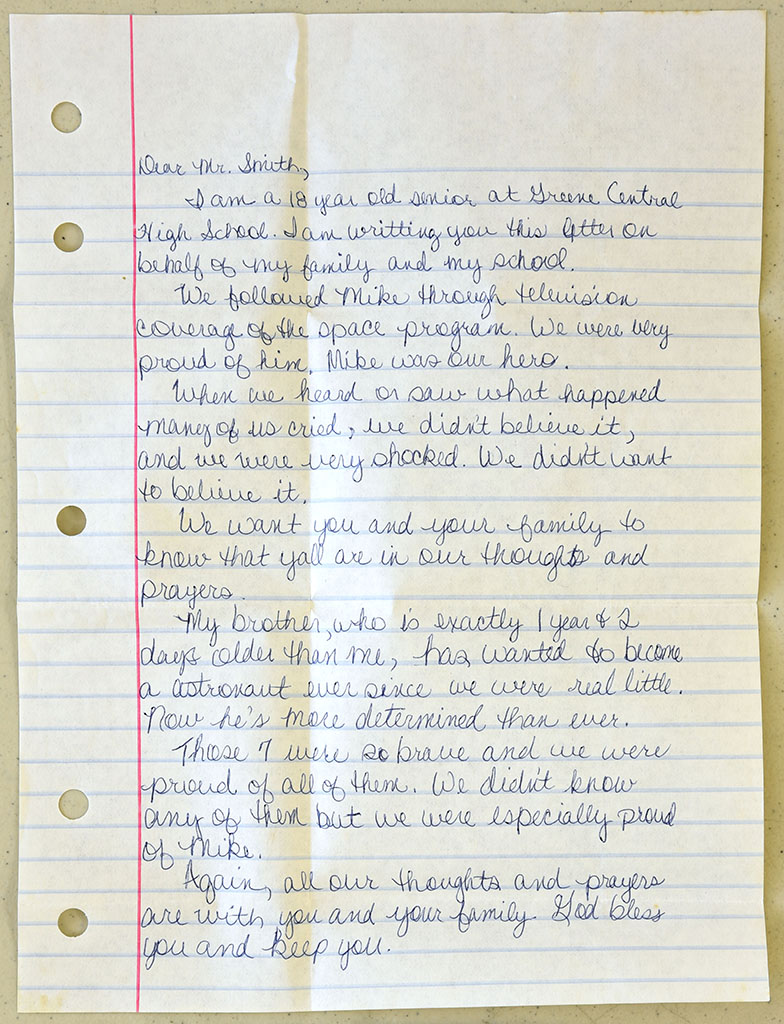

The horror of the Challenger accident played out in real time on televisions in both living rooms and classrooms, shocking not only American adults, but the nation's children as well. In the days following the accident, a high school senior named Sonya, from Hookerton, North Carolina, penned a beautiful letter to the Smith family. "My brother," she wrote, in part, "who is exactly 1 year & 2 days older than me, has wanted to become an astronaut ever since we were real little. Now he's more determined than ever." Courtesy Smith Family.

Recovery personnel retrieved the crew's official flight kit—a sixty-pound kit containing souvenirs and personal mementos—from the surface of the ocean just fifty hours after the accident. Inside that kit was this state flag, given to Mike Smith by the North Carolina Science Teachers Association. The flag's blue union has faded over the years, likely due to exposure to salt water.

Mike's wife Jane bestowed the flag to the care of Gov. James G. Martin during a ceremony on Veterans Day in 1986. In his address, Governor Martin said the flag "always brings to my mind the state motto 'Esse Quam Videri,' which translated could also have been a statement about Mike Smith—a man who exemplified this motto, 'To be rather than to seem.'" Courtesy North Carolina Museum of History.

Smith's exemplary service during his years in the Navy, the Vietnam War, and with NASA garnered him quite a few commendations. The awards include the Defense Distinguished Service Medal, the Navy Distinguished Flying Cross, the Vietnam Cross of Gallantry with Silver Star, thirteen Strike Flight Air Medals, three Air Medals, and the Navy Commendation Medal with “V.” Smith additionally received the Congressional Space Medal of Honor, awarded posthumously in 2004 by President George Bush.

Official NASA portrait of Christina Hammock Koch, taken January 10, 2014. Courtesy NASA.

The Next Generation

Following the tragic loss of the Challenger on that fateful January day in 1986, President Ronald Reagan, in a brief but powerful address, paid homage to the crew and made a solemn promise to the American people: “The future…belongs to the brave. The Challenger crew was pulling us into the future, and we'll continue to follow them.” And follow them we have, as North Carolinians watched with pride the preparations of one of our own to go to space.

Though born in Michigan, Christina Hammock Koch considers Jacksonville, North Carolina, her hometown. She is a proud alumna of the North Carolina School of Science and Mathematics and North Carolina State University, where she earned bachelor degrees in electrical engineering and physics and a Master of Science in Electrical Engineering. Koch, who was selected for astronaut training in June 2013, currently holds the record for longest continuous time in space for women. As of 2023, she remains in active service with NASA.

Since the close of the space shuttle program in 2011, NASA has had to rely upon the Russian space program to ferry American astronauts to the International Space Station (ISS). North Carolinian Christina Koch (right) made the trip to the ISS alongside NASA colleague Nick Hague (left) aboard Soyuz MS-12. As is required by the Russian government, the spaceflight was commanded by cosmonaut Alexey Ovchinin (center). Courtesy NASA.

The second half of the Expedition 59 crew launched for the International Space Station on March 14, 2019. They are pictured here in front of their Soyuz MS-12 spacecraft during pre-launch activities in February 2019. From left to right: Christina Koch, of North Carolina; Alexey Ovchinin, of Russia; and Nick Hague, of Kansas. Courtesy NASA.

American passengers of the Soyuz spacecraft wear Sokol spacesuits, modern-day variants of a design that debuted during the era of the Soviet Union. Taken the day of the launch, this photo shows Koch going through pre-flight checks and preparations in her Sokol suit at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan. Courtesy NASA.

Soyuz MS-12, carrying Christina Koch, Nick Hague, and Alexey Ovchinin, launched on March 14, 2019. Courtesy NASA.

Christina Koch (center) helps fellow astronauts Nick Hague (left) and Anne McClain (right) prepare for their first spacewalk on March 22, 2019. Courtesy NASA.

Koch, pictured here outside the ISS, made her first spacewalk on March 29, 2019. Courtesy NASA.

_0.jpg)