The Gourd Patch Turns Violent

With William Tyler in jail and the conspiracy's papers possibly in the hands of the authorities, John Lewelling felt a sudden sense of urgency. If they wanted to defend Protestantism, they'd need to take action, and fast.

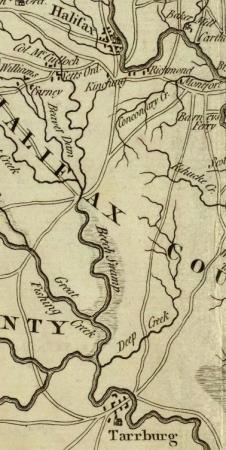

As news of May and later Tyler's arrest circulated, Lewelling and other members of the conspiracy met at the gourd patch, likely a location in Martin County near the Conetoe Swamp in the vicinity of Lewelling's home. Some men proposed to break William May out of jail on June 20, those plans were never realized. Yet, it was clear the conspiracy's aims were turning more violent. Rather than stopping at the abstract idea of kidnapping the governor, Lewelling and others in his circle began to identify other men as enemies. One new enemy of the plot was close to home, and in fact a near neighbor: James Mayo.

James and his brother Nathan Mayo lived near John Lewelling. Ardent whigs, they were involved in local politics and in the county militia. Nathan's land bordered Lewelling's, and he in fact sold Lewelling's land to him in 1772. Despite being neighbors, by the spring of 1777 Lewelling and the Mayos were feuding, and Lewelling became convinced that the brothers were somehow responsible for the recent arrests of the plot's members.

After William Tyler was arrested in late June, Lewelling and others met at the gourd patch, where Lewelling declared that James Mayo must be behind the recent troubles. Three or four men spied on Nathan Mayo, and shortly after, Isaac Barbree, at John Lewelling's son William's urging, concealed himself along a road James Mayo often frequented. Armed with a gun, Barbee intended to ambush and kill Mayo, but Mayo did not use the road that night and consequently avoided the attack.

Fight or Flight

By July 1777 neither the state's leading officials or even the plot's leadership could control the extent of the conspiracy. As the plotters paced the gourd patch and waited to hear the consequences of William Tyler's arrest, the group fragmented. Some members were ready to take up arms and violently resist the state government. Others panicked and feared they were in too deep. One of these hesitant members likely shared news of the plot with Whitmel Hill, a Martin County assemblyman and one of the plot's intended victims. By July 4th, word had spread to many of the area's leading officials that a violent conspiracy was afoot and that it's members planned to seize a powder magazine. By July 6, word went to the governor himself.

As news spread and the plan to attack Halifax unraveled, the gourd patch conspirators each had to decide the best path forward. Sometime in early July, Lewelling determined that their best solution would be to go directly to General William Howe, the commander of the British Army in North America.

1777 mezzotint of General William Howe. Courtesy of Brown University Library.

Lewelling's decision to approach Howe was a serious one. To reach Howe, Lewelling would have to travel cross enemy lines and locate the British Army somewhere in northern New Jersey or Philadelphia. Such a journey was not only dangerous, but also costly, especially when Lewelling learned that James Sherrard, a fellow conspirator and close collaborator refused to share in the cost. Contacting Howe would be a clear step towards loyalism. Lewelling and his supporters could no longer claim that they were neutrals, motivated by a zealous interpretation of Protestantism. By approaching Howe, they were taking sides. Even more seriously, providing information to the enemy, as the North Carolina state government saw it, was treason, a capital offence. If Lewelling was caught, he'd be facing the death penalty.

In early July, Lewelling, James Rawlings, the group's spiritual leader, and possibly a few other men went set out north on horseback, intending to find Howe. It was not long however until either their courage or their funds ran out, and they turned around at Scotland Neck, just north of Halifax. Without Howe, there was no one else who could help the conspirators except themselves. Everyone faced a decision of what to do next: fight or flight.

Map of North Carolina indicating the approximate location of Scotland Neck halfway between Tarboro (Tarrburg) and Halifax. Courtesy of David Rumsey Map Collection.

Flight: James Rawlings

Just before the state discovered the extent of the conspiracy, Lewelling and other leaders saw the writing on the wall. On July 5th, having failed on their mission to contact General Howe, Lewelling advised James Rawlings, a church lay reader and the plot's spiritual leader, to destroy all evidence of the plot, flee for his life, and to claim no knowledge of it if captured.

Rawlings, as he later disclosed, was not just fleeing from state authorities, but from Lewelling himself. When Rawlings objected to Lewelling's plans to instigate an enslaved uprising and refused to assist in murdering James Mayo, Lewelling declared:

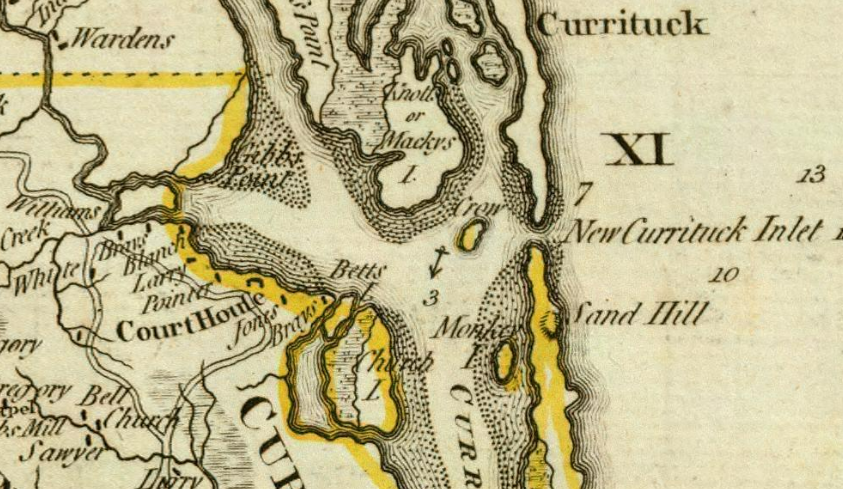

Taking his five small children and his wife with him, Rawlings got out of town as quickly as possible. It is unknown where he headed first, but it is likely he went south towards New Bern, where he waited for a time before acquiring a small sailboat. A known and wanted man, Rawlings intended to sail for Knott's Island, a place on the Currituck Sound bordering Virginia.

By early August, Abraham Jones, a local justice of the peace in Hyde County, received word that Rawlings might sail through the Pamlico Sound in his escape.

Jones spotted Rawlings' sailboat on August 2 and captured the craft, arresting Rawlings and bringing the lay readers' wife and five children with them back to New Bern.

Rawlings was confined in the New Bern jail, where he was questioned and made several depositions about his knowledge and involvement in the plot. Rawlings made a full confession and was charged with treason. He made a full disclosure of his knowledge of the plot, sparing nothing. It was from Rawlings that state officials first learned about Lewelling's plans to foment an enslaved uprising and assassinate the governor at Halifax.

1776 Mouzon Map of northeastern North Carolina, indicating the location of Knotts Island. Courtesy David Rumsey Map Collection.

The truth did not set Rawlings free however, and he continued to fear for his safety. Not only did Rawlings have to face charges, but he also feared what Lewelling might do when he learned Rawlings had made his violent plans known. Rawlings told the justices at New Bern that he had "Great Reason to fear [Lewelling] Will Make any attempts to Invalidate My Testimony... I being a poor Man have Reason to fear his power and Influence over Others to My hurt."

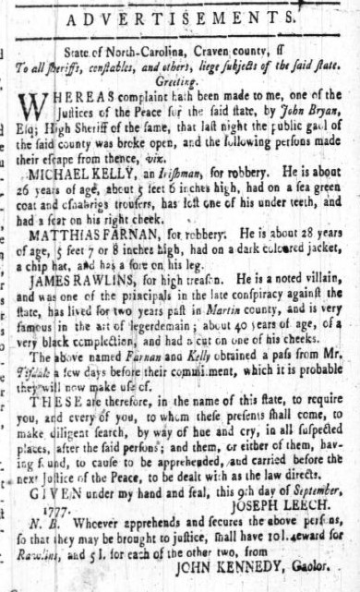

Fearful for his future, Rawlings took it into his own hands and escaped from jail during the night of September 11 along with two men charged with robbery. The wanted ad after his escape read:

Despite the 10 Shilling reward for his capture, Rawlings made good his escape and was never heard from again.

Fight: John Lewelling

On or about July 16th, Lt. Col. Henry Irwin of the Continental Army was recuperating at his home in Tarboro when an alarm rang out through the town. Irwin was a former officer in the Halifax District Militia, and he quickly gathered the local militia to face the alarm.

As Irwin discovered, a group of white planters, likely members of the Gourd Patch Conspiracy, and likely headed by John Lewelling himself. Facing them head-on, Irwin later recounted:

Signature of Lt. Col. Henry Irwin, who arrested several Gourd Patch conspirators.

The Gourd Patch militants likely had come to Tarboro to seize the powder magazine there, but ill-prepared and faced with an trained fighting force, they quickly surrendered. Many members then sat in jail while authorities questioned them and determined what to do next. When captured, John Lewelling faced a treason charge.

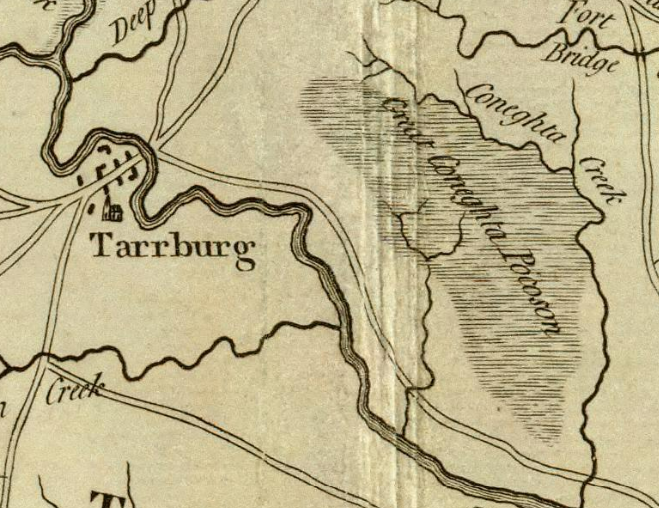

1776 Mouzon Map, indicating the location of Tarboro (Tarrburg) and the Conetoe (Coneghta) Creek, which was near Lewelling's home. Courtesy David Rumsey Map Collection.

Flight: William Brimage

William Brimage's attempt to escape from authorities is perhaps the most colorful. Brimage, a former admiralty court judge for the crown, was a prominent wealthy landowner in Bertie County. Elected to represent Bertie at the first Provincial Congress, he did not attend, but it was not enough to raise suspicion of his loyalist attachment to the crown, and he was selected as a judge for the Edenton District in 1777.

After being recruited, Brimage took the oath before Daniel Leggett and became a member of the Gourd Patch Conspiracy on July 4th. Because of his wealth and influence, Brimage immediately became a senior warden in the plot for Bertie County and was empowered to recruit new members, but it is unclear if he ever did so.

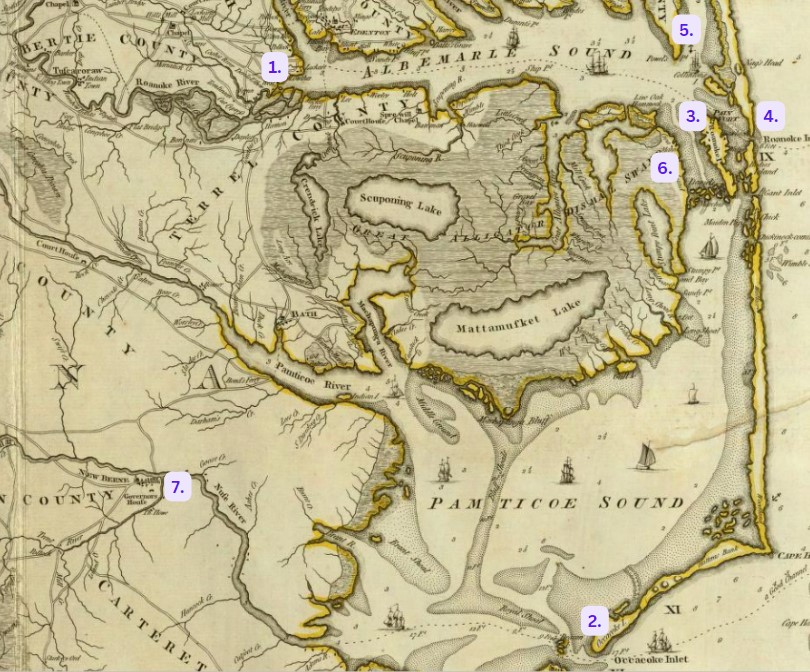

The following map highlights the key places and events of Brimage's attempted escape from North Carolina. When the plot unraveled later that July (likely after the arrest of some conspirators at Tarboro), Brimage was brought in for questioning about his involvement in the plot and later paroled. Paroled from jail but unwilling to make an oath of allegiance to the state, Brimage left his family behind at his Bertie County estate (1.) and headed towards New Bern, where he hoped to board The Brothers, aka the "Tory Brig," a ship captained by loyalist James Barzey which promised to bring crown sympathizers to British-held New York.

Brimage, however, was running late, and rather than catching the ship at New Bern, he had to meet the brig at Ocracoke Island (2.), its final stop before departing the state. Meanwhile, as state officials uncovered more alarming information about the Gourd Patch conspiracy, their suspicions about the extent of Brimage's involvement in the plot mounted. Governor Caswell personally called for Brimage's capture, stating:

Engraving of a sailing ship.

Governor Caswell ordered out the militia, instructing them to stop Brimage from boarding the brig and to bring him back to New Bern to face charges. Captain James Anderson of the Ocracoke Militia, removed Brimage from the Tory Brig on July 27 or 28. The island, however, did not have a jail, so Anderson paroled Brimage, instructing him not to leave the island until authorities from New Bern came to arrest him.

Afraid of facing a treason charge, Brimage resolved to escape the island by any means possible. Sometime on his journey, either in New Bern, on the Tory Brig, or on Ocracoke, Brimage ran into two other men two also wanted to leave the island: a man named Campbell, and John Smith, a Bertie County blacksmith. Time was ticking though, and they'd need to leave quickly before their absence was discovered.

1776 Mouzon Map of North Carolina's waterways. Courtesy David Rumsey Map Collection.

As the sun rose on July 28, Brimage, Smith, and Campbell set about trying to hire a boat that could take them north to Virginia and the safety of the British warships that patrolled those waters. Brimage made a deal with the Cornelius and Daniel Austin, two brothers who promised to row Brimage, Smith, and Campbell to Roanoke Island (3.) in exchange for $8.

Shortly after embarking on their voyage, Campbell seemed to grow restless, Daniel Austin later recalled. Rather than going to Roanoke Island, Campbell suddenly asked the Austins to take them slightly farther to New Inlet (4.) instead, promising them $10. Though Campbell said he simply "wanted to see it," it is likely Campbell and the others thought it would be easier to make their escape to Virginia from the coastal inlet.

That afternoon, once the exhausted Austin brothers pulled the boat ashore at New Inlet, the group of men found themselves on a uninhabited windswept beach looking out at the Atlantic. When Daniel Austin walked a short distance from the boat to look at the nearby shoals, Campbell followed him.

Pulling out a pair of pistols he had concealed in a handkerchief, Campbell pointed them at Daniel, declaring that he was in fact a Lieutenant on a British naval ship, and that "he must have his Boat for he must make his Escape." Cornelius heard his brother cry out at 'Lt. Campbell,' "begging for God's sake not to take his Life." Brimage and Smith seemed shocked at Campbell's sudden turn towards violence and urged the lieutenant not to shoot. Brimage declared "he would perish on the beach" lest the brothers were spared. Smith wanted no part, and asked the Austins if he could go home with them should Campbell steal the boat.

A sandy beach on Ocracoke Island, where William Brimage met the Austins. Courtesy Ted Van Pelt

A sunset on the Albemarle Sound, where the Austins fled from Brimage's group. Courtesy Jed Record

Despite Smith's and Brimage's words of support, the Austins still feared they were in danger. Cornelius asked Smith if he would help them fight Campbell but he refused, stating Campbell "was a blooded minded Fellow and was afraid he would kill some of them." In this uneasy truce, the Austins agreed that rather than lose their boat they'd take the group north to Currituck (5.), after which they'd be paid and free to go.

En route to Currituck, the weather suddenly worsened. They stopped at a small marsh island to get ballast, or small rocks to weigh down the boat and keep it steady against the rising seas. It was now that Brimage revealed the groups' true intentions to the brothers. They had hired the boat not as a mere sightseeing jaunt, but because they need to escape. Brimage and Smith "had done no harm, but being suspected Tories," were on the run. Campbell's taste for violence was his own, but Brimage and Smith assured the brothers that they merely wanted to escape the state peacefully.

Shortly after that, the stormy conditions worsened, and the group had no other choice but to pull the boat ashore and wait out the weather. They beached the boat at a placed called Dolbey's Point, somewhere on the Outer Banks north of Roanoke Island. The men all climbed out of the boat and sat on the beach. After some time, sensing that their captors were distracted, Daniel nudged his brother and they both ran for the boat and pushed off to sea.

As the Austins frantically rowed for safety, the three loyalists now found themselves stranded. Campbell somehow commandered a boat and left, presumably headed to Virginia, never to be heard from again. The Austins went to Chowan County, where they made sworn depositions about their recent experiences. John Mann, a resident of Hyde County near Roanoke Island (6.), later encountered Brimage and Smith, either on Roanoke Island or, more likely, near New Inlet, and arrested them. He brought them via boat to Edenton to face charges, where they arrived on July 30. Meanwhile the militia Gov. Caswell had sent to find Brimage at Ocracoke returned to New Bern (7.), finding their mission already had been done by a local fisherman.