Religion in Colonial North Carolina

A wide variety of Christian and Jewish people, including Quakers, Moravians, Baptists, and Catholics all called colonial North Carolina home. Despite this religious toleration, North Carolina, like all of the British Empire, only had one state-supported religion: Protestantism, and more specifically the Church of England, or Anglicanism.

In the colonial era, being Anglican, or at least Protestant, was a central part of British identity. British subjects, both at home and in the colonies, were united by the Book of Common Prayer, and by a conviction that their specific religious denomination was especially chosen by God.

British subjects felt that their Protestantism was what set them apart from their old enemies: France and Spain, both Catholic monarchies. Consequently, many British people not only celebrated their own religion, but also fervently opposed people who practiced anything different. For many people, to be British was to be Protestant. Britons believed they were among the only Europeans who were truly free, as they, unlike the Catholics in France and Spain, only answered to God rather than to the Pope.

A sense of animosity towards Catholics and the French more specifically was an undercurrent in British identity. Indeed Francophobia and anti-Catholicism was so strong that for many colonists, "no greater earthly enemy existed" than Catholic France.

St. Thomas Church in Bath, the oldest church building in North Carolina. Originally Anglican, it is now Episcopalian. Courtesy of NC Historic Sites.

Satirical print titled "Protestant & Liberty or the Overthrow of Popery & Tyranny," 1757. The print depicts Lady Justice, surrounded by Faith, Hope, Charity and Liberty. On the right, the devil and the pope attempt to weigh the scales of justice in their favor, but are unsuccessful. A metaphor for the triumph of good over evil, the print reinforces that attitude many Britons held that Protestantism and liberty were intertwined and both at odds with Catholicism. Courtesy of the British Museum.

When the American Revolution ignited and North Carolina became an independent state, religious North Carolinians found themselves lost. There was no longer a state religion, and now suddenly the state's elite spoke of a possible alliance with France and Spain, their oldest foes. Many colonists had learned every Sunday since their birth that their freedom as British subjects was constantly under threat from Catholics under the devil's influence. Now suddenly they heard that it was only through a Catholic alliance that Americans could truly be free. Such an abrupt change was hard for many of the Albemarle's farmers to accept. In contrast, it was easier to believe that a conspiracy was afoot, and that the revolutionary leadership was being led astray by evil Catholic schemers.

"To Keep Out Popery:" Origins of the Gourd Patch Conspiracy

Sometime in December 1776 or March 1777 after a meeting of militiamen in Martin County, John Lewelling approached James Rawlings looking for a favor. Lewelling was a prominent planter in Martin County and owned over 600 acres on the Conetoe Swamp. A religious man, he had served as a justice of the peace in the county and was well-known and regarded. On the way home from the muster call, he and his friend John Carter came to Rawlings seeking his blessing. Rawlings was a lay reader, or local religious leader for the Anglican Church, and Lewelling wanted his thoughts on one of the leading concerns of the day: the tension between revolution and faith. Since the Declaration of Independence, North Carolina had become spiritually unmoored from its traditional Protestant foundations. Suddenly French people were coming and settling in Edenton, and there were talks of a military alliance with Catholic France and Spain. These changes were alarming to devout farmers like Lewelling, and he concluded that he may have to take matters into his own hands. He told Rawlings:

The community needed to take a stand against these new threats to their Anglican way of life, and the state's leadership were not doing enough to uphold and protect their religious values. In fact, the new state constitution written in December 1776 stated that there was no longer an official religion. This new law, as Lewelling saw it, was only a sign of what was to come for the state's attempts to erode the importance of religion. Religious tolerance meant that Catholics would be welcomed into the state, and Lewelling was concerned. In response to these recent acts, Lewelling and Carter proposed creating a society which would promote and protect Protestant values under the new government. All members would need to swear an oath to join, and they'd pay dues for a lay reader, such as Rawlings, who could lead the society in religious services.

The society had humble, peaceful beginnings, but there was one thing that made it notable: it was a secret. Men could only join the society by invitation, and the group's activities were not discussed openly. After all, as Lewelling believed, there was a conspiracy of pro-Catholics and atheists afoot in the Albemarle Sound, so they'd need to keep their group a secret lest the anti-religion North Carolinians in power squash it. The extent and goals of Lewelling's society soon snowballed and it became a sort of conspiracy in its own right. Though never named by it's members, historians today call it the Lewelling Conspiracy, or the Gourd Patch Affair.

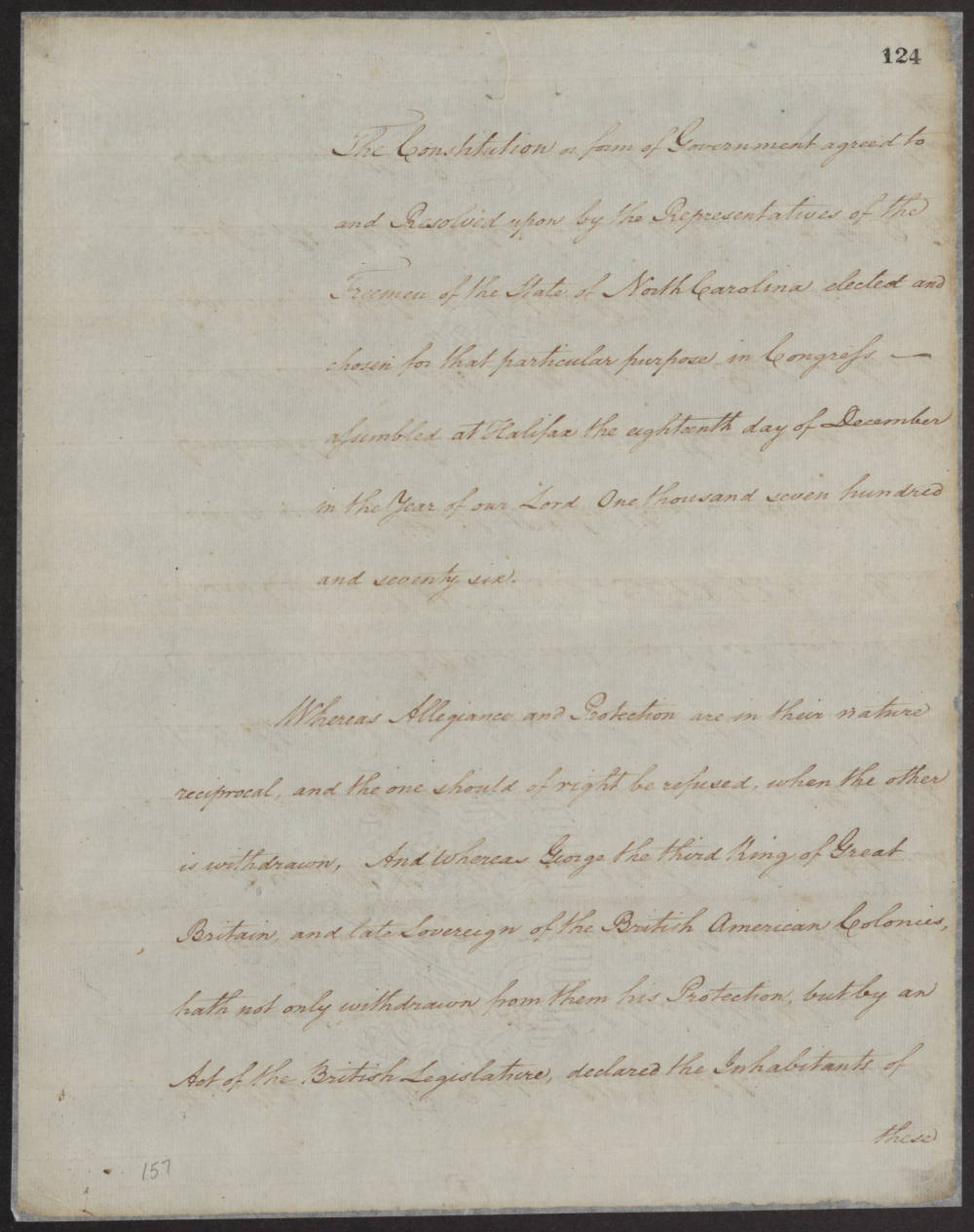

North Carolina Constitution of 1776. While it said all office holders had to be Protestant, it also stated there was no longer an official state religion, which was controversial for Gourd Patch associators. Courtesy of State Archives of North Carolina.