"Obliged to Kill all the Heads of the County:" The Plot's Intended Victims

One member of the plot, Thomas Harrison, later testified that fourteen members of the North Carolina State Assembly either held personal religious beliefs or supported religious legislation that the plot's members found controversial. These fourteen men, as the plotters saw it, were challenging many North Carolinians' identities as devout protestants and eroding religion's role in the state, and they needed to be stopped. At first the plotter wanted to stop them ideologically, but as time went on they considered using violence.

While there is no list of the fourteen politicians who the Gourd Patch Plotters saw as the leading threats, it is possible to identify some of the conspiracy's intended victims due to their unorthodox religious beliefs and status in the community.

Richard Caswell

The first governor of the State of North Carolina, Caswell had voted for a law which allowed every white male to run for office regardless of his religious beliefs.

Whitmel Hill

A representative of Martin County (John Lewelling's home) in the Provincial Congress and a Lt. Col. in the Martin County Militia, Hill denied the existence of the holy trinity.

Willie Jones

A representative of Halifax County in the Provincial Congresses and in the State Assembly, Jones was likely a deist and later requested that no priest attend his funeral.

Gunpowder, Treason, & Plot: First Arrests

Initially John Lewelling and the conspiracy's other leaders had instructed their new members "to keep out popery" and protect the Protestant religion, but it was not exactly clear how they were supposed to do so. Aside from asking for financial contributions to employ a lay reader, or unofficial spiritual leader who could lead the group in church services, Lewelling also told his new adherents to oppose the state military draft, as he feared that the state militia might help the state government in diminishing the importance of religion in the state.

By the summer of 1777 as their fears increased and the state became more insistent in collecting oaths of loyalty from its citizens, the Gourd Patch conspirators were convinced that they needed to take further action. It was no longer enough to sit out the war—instead they might need to take matters into their own hands. Accordingly, James Sherrard, Daniel Leggett, and other wardens instructed their new adherents to each gather half a pound of gunpowder and two pounds of lead shot. They may need to fight back.

Getting gunpowder and ammunition for the plot was not as easy as going to the store. Bartlet Moreland Davidson of Martin County, who later named Lewelling among his "loving friends," went to Tarboro to get powder for the group. James Sherrard and John Collins went to Windsor, where they got enough powder for five of the plotters. It was not enough though. The war had led to powder and ammunition shortages, as most of these materials were being held for the Continental Army and militia's use.

The Gourd Patch conspirators needed more powder, and to get it, they had to go to the source: a powder magazine. Black powder was volatile and had to be stored carefully to keep it safe and useable. The special ammunition storehouse was called a magazine, and major towns each had one, usually in a central secure location residents could access in case of attack.

Powder magazines had become a hotbed of activity in the early period of the revolution. In 1775 the colonial governors in Massachusetts and Virginia had seized local powder magazines for the use of British troops, sparking major unrest in those areas. Now the Gourd Patch conspirators drafted plans to seize the powder magazine in nearby Halifax, NC for themselves. It would not be easy.

Picture of the former site of the Powder Magazine in Halifax, NC. Historically this was the location of the town village green, which had many functions during the American Revolution.

Why Halifax?

Every county in North Carolina was authorized to have a powder magazine, so why would Lewelling and his fellow conspirators decide to make a raid on the magazine at Halifax specifically? Halifax was over 33 miles away from Lewelling's home in the Conetoe Swamp, and no records survive identifying any resident of Halifax County as a member of the conspiracy. Lewelling was probably motivated by a mixture of three reasons.

- Halifax, like Edenton and New Bern, was a district center, so it may have had a larger supply of powder than other county magazines.

- Halifax was the symbolic birthplace of independence in the state. In 1776 Halifax had been the home of the signing of the Halifax Resolves, a set of instructions instructing the state's delegates in Philadelphia to vote for independence.

- Governor Richard Caswell was supposed to be visiting Halifax soon. Lewelling wanted to time the raid so that they could seize the magazine and attack the governor on the same day.

A raid on the powder magazine at Halifax had its advantages, but it was not without its difficulties. At the sound of alarm, the Halifax County Regiment would immediately scramble to protect their stores. There might also be an increased military presence if the governor was in town as planned. If Lewelling wanted to be successful, he needed a distraction.

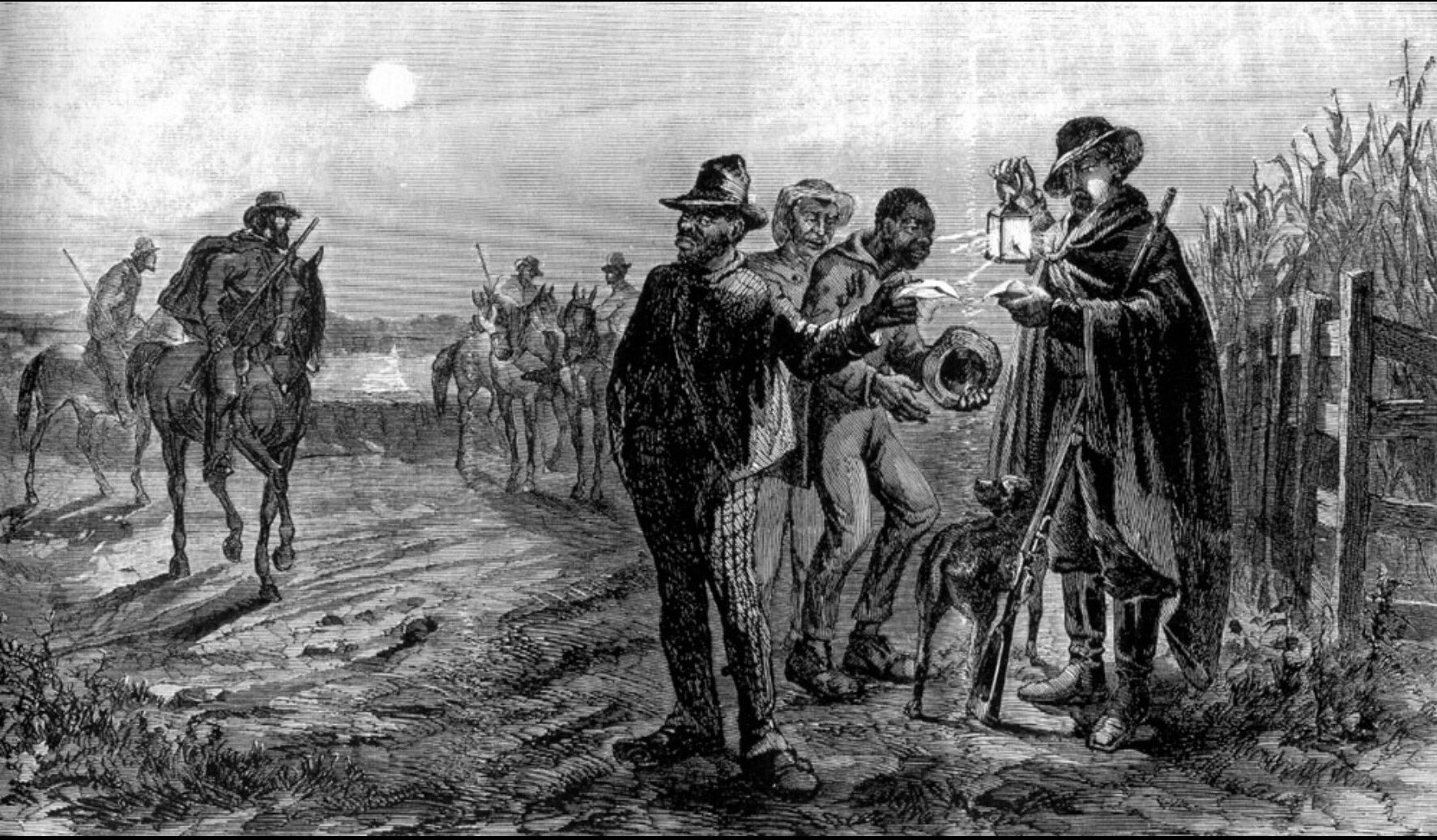

The plotters' plan for a distraction depended on one man: David Taylor. Taylor, a resident of Chowan County, was a slave patroller, or a specially appointed armed official who regulated enslaved people's movements. Patrollers policed African Americans' movements in many forms, including checking enslaved people's passes to ensure they had permission to be out, checking free African Americans' freedom papers, breaking up gatherings of African Americans, and hunting for runaway, or self-emancipated people.

After being recruited by James Rawlings, David Taylor learned about the plan Lewelling had for him. Taylor's later testimony about his involvement in the plot is scant, but Lewelling wanted him to do one of two things. Lewelling may have wanted Taylor to burst into town in Halifax and use his reputation as credibility to lie and declare that nearby enslaved African Americans were rebelling and thus draw the militia out of the town. Alternatively Lewelling may have wanted Taylor to foment an actual enslaved rebellion. According to Rawlings, Lewelling wanted Taylor to:

Sketch of a slave patroller checking an African American man's pass. Patrollers like David Taylor watched the local roads to make sure enslaved people did not escape or meet to form plans to rebel.

Lewelling's decision to instigate an enslaved uprising, or at least suggest the rumor of one, was highly controversial. For many white planters, regardless of their personal religious beliefs, their greatest fear was that of an enslaved rebellion. When Virginia's royal governor seized the powder from the magazines at Williamsburg in 1775, the colonists were angry not merely because they felt that the powder was not the governor's to take, but because they were afraid the governor was purposefully leaving them defenseless and encouraging enslaved African Americans to rise up against them. One historian has even suggested that for many white Virginians, it was this specific fear, not lofty ideas about representation or the enlightenment, that spurred Virginian colonists toward revolution.

The thought of merely proposing, let alone instigating an uprising among the enslaved people was likely too much for David Taylor, and on June 4, 1777 he and his relative Joseph went to the authorities and made depositions about their knowledge of the plot. Still, Taylor was careful and did not make mention of the possible uprising or violence, possibly because he was fearful of additional criminal charges. Instead he said the plot was focused on keeping popery out of the state.

Shortly after the Taylors came forward, William May, another member of the plot, was arrested in Pitt County. May testified about his knowledge of the conspiracy on June 19th, and the rough edges of the plot soon began to unravel.

Unlike the Taylors, May's deposition mentioned another aspect of the plot. Aside from talk of keeping popery out of the state, state officials were alarmed to hear something else: the plotters were ready to oppose the military draft, and were going to encourage others to do so.

Interior of a colonial era powder magainze. Powder kegs stored in the Halifax magazine were the target of Lewelling's planned raid. Courtesy Dennis Jarvis

Due to this alarming new information, local officials suddenly took the Taylors' depositions about the plot more seriously. Rather than a relatively innocuous, yet zealous anti-Catholic group, it now appeared that the Gourd Patch organization would stand in opposition to the new state government. Shortly after May's arrest, Pitt County officials then arrested Martin County planter William Tyler, who May said had recruited him to the plot. This latest arrest was concerning for Lewelling and the plot's other leaders, as rumor had it "old Tylor was taken with all the papers in his pocket." What would happen if the plot's constitution and other important recruitment papers were now in the hands of county officials, the very men that Lewelling feared were trying to dismantle proper Protestant society? Something had to be done.