The Gourd Patch Conspirators on Trial

The Plot Unravels: Depositions

As knowledge of the plot got out to state officials, former members of the plot made depositions, or sworn statements, about their knowledge of and involvement in the conspiracy. Some of these men came before their local justices of the peace voluntarily, and others were likely arrested and questioned.

These depositions form the majority of the documents associated with the Gourd Patch Conspiracy, and are unique because they allow the plot's members to speak in their own words, even when it is clear that many of them were illiterate and could not sign their own names.

When making a deposition, former plotters informed on everyone they knew that was part of the conspiracy, including their own family members. Local judges then used these depositions as evidence in determining which men would be charged with a crime and what their charges would be.

Historic Chowan County Courthouse, which held the Edenton District Court of Oyer & Terminer in 1777

The Charges Explained:

The Gourd Patch associators faced charges of treason and misprision of treason. The latter was more common.

Treason

Treason is the attempt to overthrow a government, to kill or injure a head of state, or to knowingly give aid to an enemy of the state. Thus, when John Lewelling, Rawlings, and others attempted to contract General Howe, they sealed a treason charge for themselves. Just like in British law, two witnesses had to give testimony against any person tried for treason.

Treason was a capital charge, meaning if convicted, Lewelling and others could face the death penalty.

Misprision of Treason

The term misprision refers to an act similar to being the accessory to a crime, or aiding and abetting one. Gourd Patch associators were charged with misprision of treason if the court felt that they had known about the conspiracy and had failed to report it to the proper authorities.

Misprision of treason was not a capital charge, but if convicted, men could face jail time, the loss of their land, or even banishment.

A Test of the North Carolina Legal System

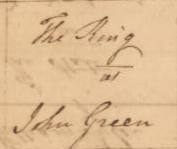

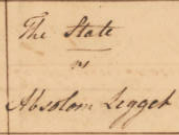

Trying the Gourd Patch Conspirators would be a groundbreaking test of the state's new legal system. In May 1777 the North Carolina General Assembly had passed legislation officially defining the the charges of treason and misprision of treason. They had also announced that every adult male in the state needed to make an oath of allegiance to the new state or leave the state in sixty days. The upcoming trial would be the first case since the new law, and the first in the Edenton District of Oyer and Terminer since the court had reopened from its pause when the American Revolution has broken out. It was also the first time a trial was titled "The State vs," rather than "The King vs."

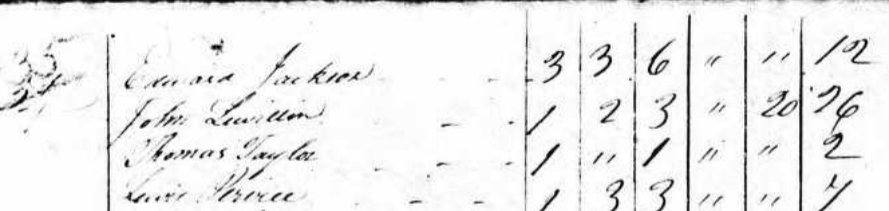

Excerpts of the Prosecution Docket for the Edenton District Superior Court, May 1778. "The King vs John Green" was the final royal case the court saw prior to reopening as a state court.

The first associator to go on trial was the plot's ringleader: John Lewelling. In September 1777, using depositions from several co-conspirators as well as a long list of witnesses, James Iredell, the state's prosecutor and future supreme court justice, put Lewelling on trial for his life. On September 20 the court's judge John Baptist Beasley found Lewelling guilty of high treason. His execution was scheduled for September 30, 1777. The remainder of the conspirators were brought before the court on charges. Some were found guilty of misprision of treason and they were all bonded out until the next sitting of the court.

The Doors of Mercy Should Never Be Shut:" Lewelling's Pardon

The court's case against John Lewelling was strong, and even before his conviction many people in North Carolina thought it would only be a matter of time before he'd face the death penalty. Still, just as his court case was a first for the state, his possible execution would be as well. As the shadow loomed ahead for Lewelling, many onlookers had opinions about what his execution might mean for the state, views that they voiced to Richard Caswell, the state's governor and one of Lewelling's intended victims.

Allen Jones, the Brigadier General for the Halifax District of the militia who was tasked with guarding the Halifax powder magazine from Lewelling's supporters, recommended no mercy for the arrested conspirators.

In contrast, Robert Smith, a lawyer in Edenton, recommended a pardon as a display of mercy.

Whatever Governor Caswell decided to do, his decision could have a profound effect on the state. Should he approve the punishment and demonstrate to the world what North Carolina did to traitors? Or he could grant a reprieve? Maybe by showing his would-be assassin mercy, Caswell could demonstrate the new state government's benevolence and sense of justice.

In weighing out his options, Governor Caswell considered several petitions from concerned members of the community who asked that Lewelling and others be pardoned. A petition from Thomas H. Hall called upon Caswell's paternal sense of mercy, reminding the governor that he had a duty to look out for the wellbeing of all the state's citizens. Caswell had good enough sense to know what was right, Hall stated, and any further arguments would be "needless as the Tears of the Widow and the Orphan" were Lewelling not pardoned.

Other petitions came from more unlikely circles. Colonel William Williams, one of the plot's intended victims submitted a petition on Lewelling's behalf. If Williams had found space to forgive his would-be killer, surely Caswell could do so as well.

One other notable petition came to Caswell's desk, and this final one was hand delivered. Mary Lewelling, John's wife, made the trek to Hillsborough to personally plead her husband's case before the governor. In making such a long journey without her husband, Mary had the escort of one of her longtime neighbors: Nathan Mayo.

Picture of Governor Richard Caswell's family bible. Courtesy of NC Museum of History.

Map of the town of Hillsborough. Courtesy of State Archives of North Carolina.

Nathan Mayo, Lewelling's close neighbor personally escorted Mary Lewelling as she sought a pardon for her husband. Lewelling and his co-conspirators had intended to kill Nathan and his brother James, as well as several members of their extended family. Nathan, a justice of the peace, had personally received a sworn deposition from co-conspirator Thomas Best, who had said Lewelling once said that "Nathan Mayo was a Very Busy Body... and that Son of A Betch would get kiled." For all that animosity, why the sudden change of heart?

One reason Nathan Mayo may have found forgiveness for John Lewelling was because Mayo was perhaps also seeking forgiveness for himself. On August 22, 1777, Mayo had a drunken dispute with one of his neighbors, Thomas Clark, about the politics of the day. When Clark expressed his support for King George III, it angered Mayo who declared Clark was a loyalist who ought to be arrested. Clark then attempted to shoot Mayo, and when he missed, Mayo went into his own home, retrieved his gun, and shot Clark, who died a few hours later. The charges against Mayo were later dropped, but whether he found forgiveness for Lewelling due to his own personal sense of remorse or for another reason, his presence as a would-be victim served to enforce the strength of Mary Lewelling's petition for clemency.

When Mary Lewelling submitted a petition to Governor Caswell, she did so not only for her husband, but also on behalf of herself and her entire family. Without John, Mary feared that she would be unable to provide for the couple's children. In addition to her husband's life, their family's property, all in her husband's name, was also at stake, and might be forfeited to the government as a consequence of Lewelling's crimes. Such a fate would leave Mary widowed, but also property-less.

Mary Lewelling's petition stands not only as a testament to the precariousness of womanhood during this period, but also points to how women could exert themselves in the public sphere. By getting the governor to sympathize with her position, Mary ultimately saved her husband's life.

In response to the petitions and the personal visit from Mary Lewelling and Nathan Mayo, on September 28, Governor Caswell and the North Carolina Council of State stayed the execution. While they did not grant him a pardon, they resolved that Lewelling's case could be considered at the next sitting of the state legislature.

In November, Lewellng's case came before the state house and senate, where the decision of what to do with Lewelling highlighted tensions between the new executive and legislative branches. Who had the right to pardon him? The legislature had made a law about treason and the justice system had determined Lewelling and others had broken it. What place did the governor have in this system? Some feared that by allowing the governor a pardoning power, that he might become too much like a king, which had been the cause for the whole revolution in the first place.

The house and senate ultimately decided that Lewelling ought to be executed. However, they added the caveat that if the judge in Lewelling's case had further information, they might reconsider the case. Accordingly on December 2, 1777, judge John Baptist Beasley asked Governor Caswell a pardon on Lewelling's behalf. He wrote:

With the letter, Judge Beasley made it clear that even he thought the sentence was unjust for Lewelling's crime. He asked for mercy, both for Lewelling and for his family. Based in part on Beasley's letter, as well as the number petitions he had previously received, Governor Caswell granted Lewelling a pardon, the first of its kind for the state. While the pardon does not survive, later evidence such as census records and Lewelling's 1794 will demonstrate that he, like most other members of the Gourd Patch Conspiracy were granted clemency.

Picture of a 1790 census for Martin County. The entry lists John Lewelling. It further states he enslaved 20 people at the time of the census.

During the 1778 term of the Edenton District court, charges were dropped against most of the remaining members of the conspiracy, likely after they swore an oath of allegiance to the State of North Carolina. William Brimage, a large landowner and prominent former judge refused to take the oath and was expelled from the state, leaving his family behind. One of the only other men not to have his charges dropped was the movement's spiritual leader, James Rawlings, who had fled from the New Bern jail never to be seen again.

.jpg)